The most attentive people I know are birdwatchers.

They are less sleepy as a whole than the general population.

— Anne Lamont in Dusk Night Dawn

This article is for the birds.

No, I’m not writing something trivial or meaningless. I mean, literally, this article is about avian creatures. Or as ornithologist, professor and poet J. Drew Lanham put it in an online talk offered by The James Museum this summer, “I write about birds, for birds and to birds.”

Unlike Lanham who wrote passionately about his fascination with birds since childhood in The Home Place: Memoirs of a Colored Man’s Love Affair with Nature, I never paid much attention to the things with feathers when I was young. I did have a pet canary named Tweetie when I was 12 but when he died I swore I would never cage another creature again.

Later while living in France I made the acquaintance of a parrot named Coco whom I tried to teach English. Coco, however, had totally embraced his adopted land and would only speak French. One day when he began repeating “J’en ai marre, J’en ai marre” (Translation – “I’m fed up. I’m fed up”), I thought with some excitement that he was having an existential crisis á la Jean-Paul Sartre. But his French owner set me straight. “He’s a parrot. He’s just repeating what I say when I have to clean up the bird seed that he scatters across my kitchen floor.”

No, my current infatuation with birds is a recent phenomenon. It began during last year’s lockdown, thanks to my new routine – daily walks through the Pink Streets, my neighborhood in south St. Petersburg. Hiking along the narrow stretch of Pinellas Point Park, which runs along Tampa Bay, I saw — and heard — tiny warblers chattering furiously as they flitted from tree to tree (probably warning each other that a very large creature was passing by), graceful seabirds soaring across the water, splashing into Tampa Bay as they dive-bombed for a fish meal and red-feathered creatures peck peck pecking away on pine trees in search of a tasty snack of insects or maybe building a new home.

I didn’t have scientific names for any of them (those peck peck peckers were no doubt some sort of woodpecker species), but I began to think of them, thanks to Emily Dickinson, as symbols of hope.

Hope is the thing with feathers

That perches in the soul

And sings the tune without the words

And never stops – at all –

I also discovered that I am living in a state that is a birder’s paradise.

For decades ornithologists (those who study birds) and birders (those who seek them out, listen for their calls and check their sightings off a list) have been, well, flocking, to Florida to view the more than 500 bird species that have been spotted here. Some birds — the Florida Scrub-Jay, the Mangrove Cuckoo, the Snail Kite and the Florida Grasshopper Sparrow — can be seen only in Florida.

The Florida Scrub-Jay is the only bird endemic to Florida – that is to say, native and not found anywhere else in the world.

In 1951 the Pinellas National Wildlife Refuge, a breeding ground for herons, cormorants, egrets, endangered brown pelicans and many more bird species, was created on small islands off the coast of St. Petersburg. The birds nest peacefully on these islands in sea grass protected from interference by motor boats (which are forbidden to approach). One of the islands of the refuge — Tarpon Key — hosts the largest brown pelican rookery in the state of Florida.

Nowadays, however, all is not so hopeful in Florida birdland. Many bird species that were plentiful here up until the last century are now extinct. The last Dusky Seaside Sparrow, held in captivity, died at Disney World in 1987. The Carolina parakeet, the only parrot species native to the Southeastern United States, was last observed in the wild in the ‘20s. Its last known nesting location was near Gum Slough within Kissimmee Prairie Preserve State Park.

Other bird species are in serious trouble, with the Florida Scrub-Jay heading that list. According to the Audubon Society, as of the early 1990s, the total population of Florida scrub-jays was estimated at about 4,000 pairs, probably a reduction of more than a whopping 90 percent from its original numbers.

Human development has nearly wiped out the bird’s only natural habitat – scrub land. Florida scrub, which once could be found in 39 counties, is now only found in a handful, threatening the scrub-jay’s survival.

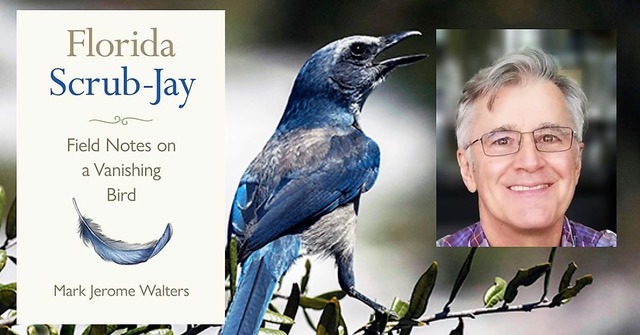

In a new book out this year, Florida Scrub-Jay: Field Note on a Vanishing Bird, Mark Jerome Walters chronicles just how dire the situation is for what might be the world’s most friendly bird. To assess the scrub-jay’s chances for survival, Walters, a veterinarian, journalist and professor at the University of South Florida St. Petersburg, travelled up and down the state to seek out the sandy upland regions where scrub-jays still can be seen – on the Atlantic Coast on Merritt Island (home of the Kennedy Space Center and the Merritt Island Wildlife Refuge), on the Gulf Coast near Sarasota, on Lake Wales Ridge and in the Ocala National Forest.

Taking his readers back and forth in time (we even get to ride with his grandfather in a car in 1925 along the St. Johns River, then lined with scrub and thick with scrub-jays), Walters tells the story of the bird’s remarkable natural history. Arriving in Florida about 2 million years ago from the west, the songbird settled in the sand dunes in the central highlands of Florida. When it was cut off by rising waters from its former western habitats, the scrub-jay developed here into a unique species – a bird with a long, graceful tail, blue feathers and an amazingly friendly disposition.

At Cruickshank Sanctuary in Marion County, one even landed on Walters’ head.

Which is pretty remarkable when you consider that the Florida Scrub-Jay is a direct descendent of the seven-ton T-Rex (almost 100 million years removed, according to Walters, but still).

“Modern birds such as the Florida scrub-jay are not like dinosaurs,” he writes. “They are dinosaurs — every bit as much as T. rex. a member of the dino group from which birds descended.”

It’s a story of survival but it’s also a sad story as massive land-reclamation and canal-building projects in the 20th century destroyed most of the ancient oak scrub heartlands that the Florida Scrub-Jay depends on.

Walters still has hope for the scrub-jay though. He introduces us to a number of people fighting for its survival. Some have been tracking the remaining birds for decades, meeting for annual counts of the species in the small areas of scrub still left. Others are purchasing land to create wildlife refuges where the scrub-jays can thrive and in some cases are relocating the birds in an effort to increase their numbers.

In Ocala National Forest forest rangers routinely mimic forest fires through prescribed burnings in order to recreate the sand pine scrub the birds need to survive. Scrub-jays hate Smokey the Bear, Walters points out. Natural forest fires, after all, are what created the bird’s habitat in the first place.

“There is no reason this bird has to suffer the same fate as the Dusky Seaside Sparrow and so many other birds,” Walters says in an interview posted on the Newsroom site at USFSP where he teaches journalism. “But it won’t happen on its own. People will have to help.”

Lanham agrees. “Conservation is activism,” he told us in his online James Museum talk. “If it’s done right, conservation is not conservatism – you don’t sit back and let things remain the same.”

For example, what should be the legacy of such conservationist icons as John James Audubon, who owned slaves, and John Muir, who characterized Blacks as lazy “sambos” and Native Americans as “dirty”? Lanham addressed this question in a provocative piece that was published this spring in none other than Audubon Magazine. In “What Do We Do About John James Audubon?” Lanham lauds the Sierra Club (Muir was its first president) and the Audubon Society for denouncing the racism of these men whose names are so linked to their organizations.

“Yes, they were “men of their time,” says Lanham, but they “could have been men ahead of their time and judged accordingly.”

As for the possibility that Audubon may have been Black himself, Lanham says, “Audubon may have passed as white, but most importantly, he passed on the chance to be a better human being.”

Seated in his side-yard writing shack, a converted storage shed that he calls The Thicket, Lanham talked poetically about his interest in wild places and his adoration for birds. A native of South Carolina, he was Zooming in from that state where he is now a professor of Wildlife Ecology and Master Teacher at Clemson University. The Thicket, not surprisingly, was decorated with antlers, a marionette of environmentalist Aldo Leopold (his hero) and artwork depicting an Ivory Bill Woodpecker, a Carolina Parakeet and a Swamp King Warbler.

In his memoir, Lanham describes his ancestry as “mostly black” but also “an inkling of Irish, a bit of Brit, a smidgen of Scandinavian, and some American Indian, Asian, and Neanderthal tossed in, too.” Although he fits most of labels usually associated with birders — middle-aged, middle-class, well-educated and male — as a man of color, Lanham is well aware that he is an anomaly in the world of birding (something another Black man was painfully made aware of last year in Central Park). “The chances of seeing someone who looks like me while on the trail are only slightly greater than those of sighting an ivory-billed woodpecker,” he writes in The Home Place.

In 2013 Lanham famously wrote an essay called “Nine Rules For The Black Birdwatcher” which appeared in Orion magazine. It began “1. Be prepared to be confused with the other black birder. 2. Carry your binoculars — and three forms of identification — at all times. 3. Don’t bird in a hoodie. Ever.”

That essay is reproduced in his delightful new book out this year, Sparrow Envy, which includes dozens of his bird poems. In “Octoroon Warbler” he renames birds who were named after “self-serving white-supremicist men with the self-serving penchant of naming things after themselves.” In “No Murder Of Crows” he rejects the bloodthirsty word usually used for a group of those birds –

They were silent as coal,

headed to roost, I assumed,

a congregation I refused to call a murder

because profiling ain’t what I do.

Birds, of course, don’t care what you call them. But we can learn a lot by observing them, Lanham says. In all his time wandering in nature, he points out, not once did a wild creature question his identity.

“Not a single cardinal or ovenbird has ever paused in dawnsong declaration to ask the reason for my being,” he writes in The Home Place. “White-tailed deer seem just as put off by my hunter friend’s whiteness as they are by my blackness. Responses in forests and fields are not born of any preconceived notions of what ‘should be’; They lie only in the fact that I am.”

“As we develop some empathy towards one another and nature, we can come together,” Lanham told us from his perch in The Thicket. “That’s the only way we can survive and thrive.”

– – –

Birdwatching in Tampa Bay

ERGO SUM: A CROW A DAY

Now through September 6, 365 panels of crow paintings are on display at The James Museum in an exhibit sponsored by Bayfront Health St. Petersburg, Bayfront Health St. Petersburg Foundation and USF Health Byrd Alzheimer’s Center and Research Institute.

In 2010 Canadian-born artist Karen Bondarchuk’s mother was diagnosed with dementia. Four years later Bondarchuk decided to paint a crow a day on small hand-cut panels for a year. “The series is simultaneously a marker of my mother’s lost time and a constant reminder of my own days, my life, and an attempt to signal visually the preciousness and individuality of each day,” she explains.

“Bondarchuk’s series is a touching tribute that reminds us that time is fleeting and beautiful,” says Emily Kapes, curator of art at The James Museum. “I think this exhibition will resonate with anyone who has experienced the decline or loss of a loved one.”

Details here.

PEAHENS AND SCREECH OWLS

In a feature last spring entitled “Birds of a Feather,” two “eagle-eyed readers” answered The Gabber’s call to send in wildlife photos. They sent pictures of birds to the Gulfport-based independent weekly newspaper.

“Phyllis Marcum snapped a shot of a peahen – that’s a lady peacock – strutting down Beach Boulevard on an early morning walk, and Robert and Kasara Barto got friendly with a small screech owl hanging out in their Ward 4 backyard,” The Gabber reported.

WOOD IBISES, WOOD STORKS AND COMMON GALLINULES

The city of Gulfport has placed a new sign in Wood Ibis Park at 58th Street South and 28th Avenue that identifies and gives information on three local bird species – the Wood Stork, the Common Gallinule and the park’s namesake, the American Wood Ibis.

Designed by Kristin Ossola, Gulfport’s technical event specialist, the sign was suggested by Gulfport resident Margarete Tober. Park-goers can scan the sign’s QR code on their mobile devices which will take them to the Ibis Wood Park Bird Guide on mygulfport.us, the city’s website where 18 pictures of birds found in the area are posted.

Click on a photo of a bird and you will be directed to the audubon.org site which provides detailed information about the bird, including the effect of climate change on its survival chances.

WARBLERS, VIREOS, THRUSHES, FLYCATCHERS, TANAGERS, ORIOLES, SHOREBIRDS, HAWKS, DUCKS, SKIMMERS, TERNS, PLOVERS, EGRETS, HERONS, GULLS AND MANY OTHERS

Fort De Soto Park, located along the Gulf Coast, is a popular stopping place for birds during their spring and fall migrations. It has become internationally famous as one of the premier birdwatching locations in the Eastern United States.

The Fort De Sota Park Checklist for Birders is based on documented bird sightings in the area over the past 60 years. It tracks the overall status of these bird species in the park as well as on the Pinellas Bayway and Shell Key, a county-owned preserve just south of the park. The three locales cover more than 2,000 acres.

During spring migration — from March through mid-May — thousands of birds migrating north across the Gulf of Mexico en route to their breeding grounds in the U.S. and Canada, stopover at Fort De Soto Park. The heaviest concentration of birds usually pass through in spring from the second week in April to the first week in May. Fall migration takes place from August through November.

During both the spring and fall migrations, families of wood warblers as well as vireos, thrushes, flycatchers, tanagers, orioles and many more can be spotted.

Wintering birds, including shorebirds, hawks and ducks, start arriving as early as late July and can usually be found at North Beach and the end of East Beach. Check for puddle ducks at the pond a half mile before reaching the park entrance. Occasionally, sea ducks, gannets and jaegers can be seen from the Gulf side of the park.

The lowest diversity of species is seen during the summer season. The Mangrove Cuckoo, Black-whiskered Vireo and Prairie Warbler no longer breed in the park, but thanks to local Audubon Society volunteers the breeding areas for species like Black Skimmer, Least Tern and Wilson’s Plover are still protected. Wading species like the Reddish Egret, Great Blue Heron, Great Egret and Snowy Egret are plentiful.

Gulls and terns are in the park all year round.