March 11, 2020 | By Margo Hammond

. . .

This is a story of a family legacy in the arts. It starts near Miami, long before that city became the art hub it is today, travels to St Petersburg and then goes full circle back to present-day Miami.

It involves an exiled community, an underground art gallery, two former mayors of Miami (one Democrat, the other Republican) and a grandson determined to honor his 84-year-old grandfather’s support of Cuban artists with a street sign.

Oh, it also involves an exhibit in a bathroom during last fall’s Miami Art Week.

I learned this story from that determined grandson, Antonio Permuy, whom I met when he offered his social media skills, pro bono, to Bijoux Bios: Every Piece of Jewelry Has a Story, a storytelling project I’ve co-founded with fellow journalist Jaye Ann Terry. Antonio and I bonded over the love a good story.

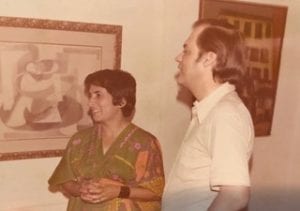

Antonio’s story begins with that underground gallery. The Permuy Gallery was one of the first Cuban art galleries in South Florida following the Cuban Revolution. It was launched in the early ‘70s by his grandfather, Jesús Permuy (an architect and urban planner, political activist and art collector) and his grandmother, Marta Permuy (an art dealer).

The gallery, run out of their apartment in Coral Gables, lasted only five years — until the mid-‘70s — but the Permuy Gallery would have a lasting effect on the artists who exhibited there and on the then struggling art scene in Miami.

“That early art world could not have happened without them,” says Lynette Bosch, author of Cuban-American Art in Miami: Exile, Identity and the Neo-Baroque.

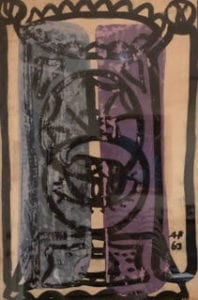

Jesús Permuy first met two of the artists who would eventually exhibit at the Coral Gables gallery in the late ‘50s when he was a student of architecture at the School of Architecture and Planning of the University of Havana — Amelia Peláez who had been commissioned in 1958 to mount a gigantic mosaic mural at the main entrance of the new Habana Hilton Hotel, and José Maria Mijares, an avant-garde artist who was one of the Diez Pintores Concretos, a prominent art movement in Cuba at that time.

He met them when he was designing layouts for Espacio, a student-run design magazine where he eventually served as director. Jesús attracted the attention of Cuba’s artists when, as cultural secretary of the University Student Federation, he organized an art exhibition called Operación Cultura which reached out to artists living in rural parts of the country to come to the campus to exhibit, something that had never been done before.

Then in 1959 Fidel Castro marched into Havana. The Havana Hilton was rechristened Havana Libre and in the wake of the Cuban Revolution Mijares and dozens of other artists went into exile, most of them settling in and around Miami. Some like Mijares and Rafael Soriano, who had been one of the founders and director of the Escuela de Bellas Artes de Matanzas, the most important art school in Cuba outside of Havana, were already famous. Others were just launching their careers in painting, ceramics and sculpture — Lourdes Gomez-Franca, an expressionist painter who suffered from schizoprenia; Juan Gonzalez, who left Cuba in 1961 when he was only 19; the metal sculptor Rafael Consuegra and painter Emilio Falero who both studied with Soriano at Miami Dade College, and the abstract painter Baruj Salinas.

Famous and not-yet-famous alike, these artists soon found out that there were few outlets for their work in their adopted country.

Already politically active in the counter-revolution against Castro in Cuba, Jesús Permuy also went into exile in Miami where he continued his political activism and launched his career in architecture and urban planning. Throughout the 1960s he worked on a number of architectural projects in Florida, including the New World Tower, a 30-story tower in downtown Miami, and the Clearwater Marine Aquarium. In the ‘70s he advocated for the establishment of Little Havana’s Jose Marti Park (it was he who recommended its present-day site on the Miami River). In 1974 he founded the Center for Human Rights of Miami.

But it was his establishment of the Permuy Gallery in that Coral Gable apartment that endeared him to a generation of artists left adrift by the Cuban revolution.

Not only did the gallery give dozens of Cuban artists much-needed exposure, it provided a place for them to meet and exchange ideas not unlike the artists who decades earlier had gathered in Montmartre and Montparnasse. Even artwork by artists who had stayed behind in Cuba — Amelia Peláez, the internationally recognized Rene Portocarrero (whose tiled mural had been installed in the Hilton Havana’s Antilles Bar just before Castro’s march into the city) and Victor Manuel Garcia Valdés, an early member of the Cuban avant-garde movement, for examples — found its way onto the walls of the Permuy Gallery. In some cases people who collected these work had brought the canvases to South Florida with them. In other cases it was the artists in Cuba themselves who figured out ways to get their work to the gallery

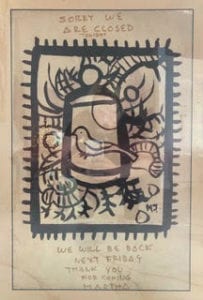

Even after the gallery closed, the Permuys continued to host regular Friday night salons and private exhibits attended by Cuban artists, collectors, writers, politicians and business leaders.

Reverberations from those artistic soirees are still being felt in Coral Gables. Every month that city holds Friday Gallery Nights, a tradition inspired by the weekly gatherings at the Permuy Gallery.

Jesús and Marta Permuy also passed down their love of art to their children and grandchildren.

Ignacio, their eldest son, who became an architect, carries on the family tradition of collaborating with artists. The founder and president of Permuy Architecture in Coral Gables, he worked with Carsten Höller in 2017 to install the Belgian sculptor’s nine-story-tall tandem slide at the entrance of Aventura Mall in Aventura, Florida.

Permuy Architecture is also collaborating with Dutch artist Jan Hendrix to imprint a design on the glass facade of the Edge on Brickell, an ultra-thin 50-story condo the firm is proposing to build along the Miami River. “Envisioned as a breathtaking staple for Art Basel Miami,” Hendrix’s design, which the company says will be one of the largest artworks in the world, will light up in the evening, thanks to color-changing LED lights visible from the river. “This unprecedented concept allows the building occupants to live within a functional work of art,” the company boasts on its website.

In 2018, Permuy Architecture, in lieu of a corporate holiday office party, began to host an annual Art + Architecture exhibition at the firm’s Coral Gables headquarters featuring art from the Permuy collection. Always held on a Friday, it is a nod to those Friday Gallery Nights once held in Jesús’ and Marta’s Coral Gables apartment. Last year’s event featured art by Baruj Salinas and the late José Mijares,

Antonio, who works as communication manager at Permuy Architecture, is also deeply involved in the arts. During his sophomore year at the University of South Florida St. Petersburg, he founded The Collection USFSP, an art appreciation club which worked closely with Ann Wykell, the campus Public Art Coordinator, to bring artworks to campus. In 2017, for example, the club was involved in installing St. Petersburg artist Ya La’Ford‘s facelift of the Family Study Center, a mid-century structure on the northeast corner of campus.

After graduation, Antonio joined up with Taryn Barnett, a fellow curator and artist whom he had met through the art club, to launch an arts project of their own: the St. Petersburg-based BlackOUT Art, LLC, which aims to install art in unexpected places to “change the relationship between art, artist and participant.”

Launched last October at Gulfport’s Historic Peninsula Inn with a pop-up exhibition of community art, the duo also set up a unique installation as part of JADA Art Fair’s Miami Art Summit held in an abandoned building during this year’s Miami Art Week (which notably includes the internationally-famous Art Basel). “We wanted to choose the least desirable space to usurp people’s expectations,” says Antonio. “So we took the bathrooms.”

And that street sign?

Tomas Regalado, a former mayor of Miami, was the first to try to get a street named after Jesús Permuy to thank him for his work for Miami’s Cuban community, not only his work in the arts but also his work in human rights. It turned out, however, that the city only affords that honor to someone after their death and Jesús is very much alive. Then Antonio took up the cause.

“I found out that the county was much more flexible about this being alive thing,” he laughs. So he sought the help of Xavier Suárez who had been the first Cuban mayor of Miami and who was now a county commissioner. His grandfather lived in Suárez’s district and they went way back.

It worked. Last month, Miami-Dade County honored Antonio’s grandfather by designating a portion of South Miami Avenue between S.W. 26th Road and U.S. Route 1 as “Jesús A. Permuy Street.”