February 2, 2021 | By Margo Hammond

Using Creativity to Spark Problem Solving

and Empower Women

. . .

. . .

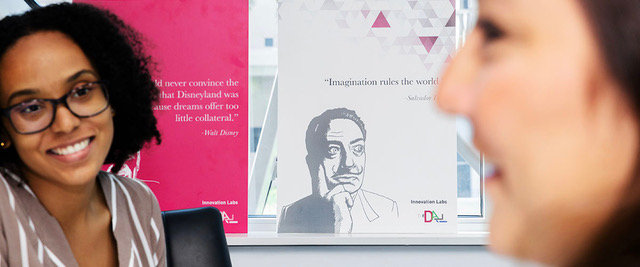

Salvador Dalí, the wide-eyed artist of melting watches and lobster telephones, may not be the first name you would associate with corporate board meetings and financial portfolios, but for the past six years the Surrealist painter has been teaching businesses the art of creative problem solving.

Since 2015 (after a successful BETA trial), hundreds of companies have sent their employees to attend programs tailor-made for business needs at The Dalí Museum’s Innovation Labs. Businessmen and women — as well as members of nonprofit boards and, in some cases, individuals — have learned how to solve problems, thanks to Dalí’s art, philosophy and methods combined with state-of-the-art research into creativity.

“There are valuable lessons to be found in all art,” says Kimberly Macuare, the co-director (along with museum director Hank Hine) of Innovation Labs. “However, I do believe that Dalí is the best teacher of all because we know that creativity comes from making connections that other people don’t make… connecting things that don’t necessarily belong together. And that is something that Dalí excels in. He is a master of juxtaposition.”

Dalí is also a master at challenging perspectives. In his Cubist-inspired paintings, for example, he presents an object from many angles at the same time. In his double image works, what you see changes before your very eyes – with a tilt of the head or with a squint of the eyes, another image emerges.

Macuare uses all of these creative aspects of Dalí’s works to help groups solve specific problems examined in the Innovation Labs.

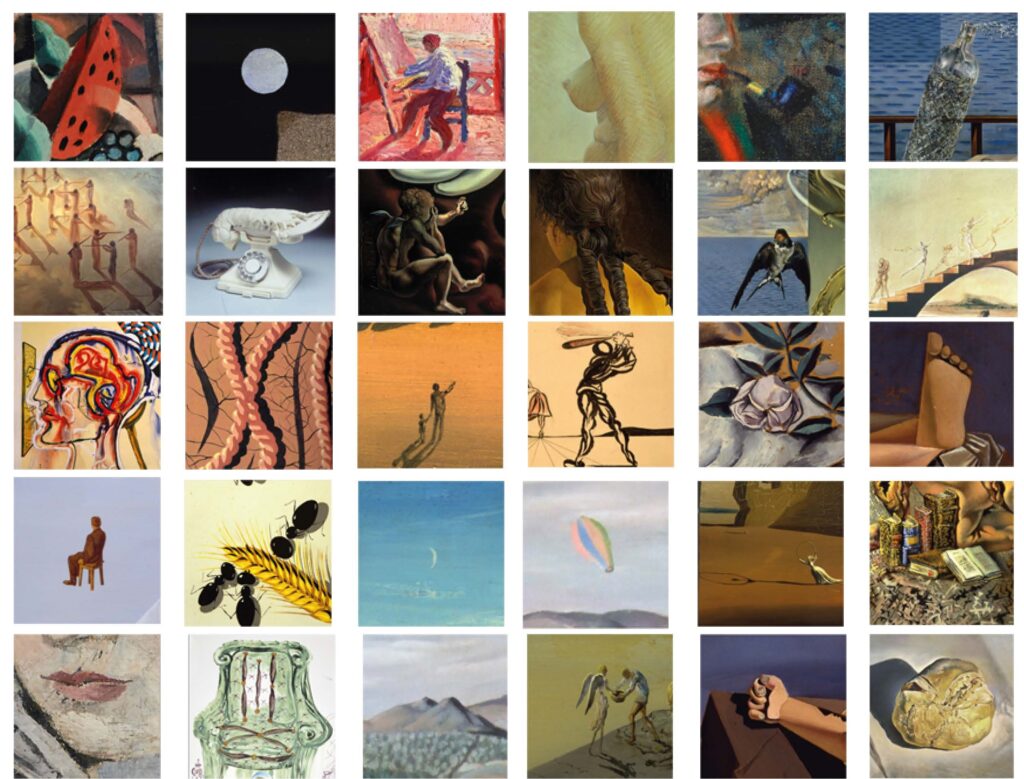

She demonstrates, for example, the power of juxtaposition, creating radical combinations and prompting discussions through the use of a set of visual image cards, details from Dalí’’s works, during her sessions online. “I lay out the cards and ask everyone to grab an image that best connects with how they are feeling about an issue or situation — for example, top of mind for many currently is the COVID situation — and then they share their thoughts with each other,” she explains. “You immediately get to a much deeper level of understanding within that group than if you said, ‘Oh how is everyone feeling today?’ and get people’s scripted answers.”

Some people choose the same image, of course, but they interpret it in a vastly different ways.

Before the pandemic when the labs sessions were in-person, she showed Dalí’s Still Life: Sandía (sometimes called Cubist Still Life with Watermelon), painted in 1924 to a group that managed the real estate portfolio of a finance company to teach a lesson in perspective. The group was tasked with juggling the competing needs of the company itself, the employees of that company, the customers who came to the company’s facility and the stockholders.

“The group needed to practice the kind of thinking that went into Dalí’s Cubist painting,” says Macuare. “That kind of thinking served as a jumping-off point for how in a specific situation the group might examine its problems from all its different angles at the same time.”

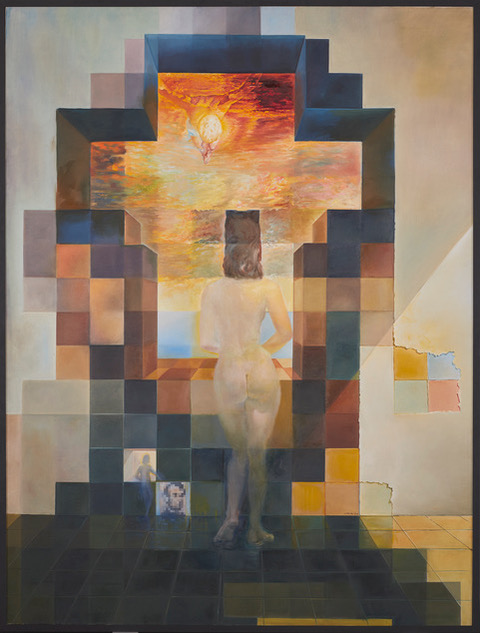

Also pre-COVID, Macuare used a Dalí double image painting — Gala Contemplating the Mediterranean Sea Which at Twenty Meters Becomes the Portrait of Abraham Lincoln, painted in 1976 — as part of the Women’s Empowerment Program, launched by Macuare as one of her first projects when she began with the Innovation Labs in 2018. The labs partnered with Dress for Success (which works to help women gain employment) and The Spring of Tampa Bay and CASA (both of which work with domestic abuse survivors) and offered workshops to the women who are served by these organizations as well as the organizations’ employees and boards.

The double image painting offers the women an opportunity to examine the power of changing perspective. “Gala Contemplating the Mediterranean can offer an important mind shift for people,” explains Macuare. “They realize that sometimes being able to change your perspective gives you the ability to understand something in a different way. Dalí is exemplary among artists for taking one perspective and then turning it on its head to give you the opportunity to see something differently. Like the mantra in our labs – See Differently. Do Differently. Be Differently.

“One of the things that the creative problem solving process is predicated on,” she adds, “is that if you mindfully move through this process, you can come to an understanding and a solution to problems that you face. And that is an innately empowering process — to realize that the answers to the challenges you seek are within you.

“We wanted to think of how we might leverage this not just to empower companies and to empower employees within companies to solve problems and face challenges but how might we do this with other groups… Over 60 years of research have been dedicated to studying creativity and what we have learned is creativity itself is universal.”

Everyone, it turns out, has the potential to be creative.

“People, once they get past childhood, feel very intimidated by artistic activity — there’s no way to scare adults more than to put art materials on the table — they come to believe that only artists are creative,” she says. Unfortunately, this is reinforced when business magazines put a picture of paint brushes on their covers to represent the creative process, implying that only artists are the creative ones. This, says Macuare, is wrong-headed.

“In the Innovation Labs, I have tried to help people understand that art is not a metaphor for creativity. Rather, art offers us a way of thinking that if we copy and emulate and adopt it, it will help us better think through any kind of problem,” says Macuare.

“There’s a real value in thinking about artists, whether they be literary or visual artists. Unlike people who work in business and science, artists think of themselves as being involved in a creative endeavor – and because of that, they have come up with incredible philosophies, methods and processes to access that creativity, to stimulate it. Whereas businesses have often thought of the process of innovation as being some kind of rote process they could follow, a formula, if you will, that they could employ in order to incrementally improve a product rather than seeing that innovation is and always must be a product of creativity. There is no innovation without creativity.”

Macuare holds a BA in English from the University of Cincinnati, an MA in English and a PhD in English with a specialization in medieval literature and economics, both from The Ohio State University. She came to The Dalí after 20 years of teaching where she sadly witnessed an increasing divide between the humanities and science.

“The divide is very artificial and damaging for both ends of the spectrum,” she says. “When you have people who are from the humanities and they are working with business and science, they can often offer perspectives and ideas that others would not normally come up with because it’s not part of their training… this is something that great innovators have understood. Steve Jobs is probably the best example of that, somebody who deeply understood the value of humanities as applied to technological innovations. I’m very inspired by that.”

In addition to Dalí as a visual artist, Macuare also employs the talents of Dalí the writer. She is currently in the process of creating another set of cards — this time using words, not images — from Dalí’s book 50 Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship, inspired by musician and artist Brian Eno’s Oblique Strategies Cards.

. . .

“Writers have always seen themselves as being involved in a creative process and how they go about that process can be informative for businesspeople,” says Macuare, who regular writes profile pieces of innovators of the 20th and 21st century for Technology and Innovation: The Journal of the National Academy of Inventors where she is an associate editor. “One of the best ways to gather data about a problem, for example, is an old writing trick – a zero draft. You basically sit down and write everything you know about the problem and you don’t worry about punctuation and you don’t worry about your style and you don’t worry about organization. You just write down everything that you know so that you can get everything down on paper. And then you can go back and mine that zero draft for your hot spots and your insights”

She also encourages Innovation Labs participants to write down a leadership philosophy (a practice she adapted from her academic days of being asked to write down a teaching philosophy) and — appropriately enough for work in a museum dedicated to Dalí — to try the Surrealist practice of automatic writing. “Like the zero draft, the Surrealists just sat down and started writing to see what bubbled up,” she says.

The Innovation Labs, which currently offer both digital and socially distanced in-person workshops, actually comprises three different types of labs — Foundation Labs, Skills Labs and Solution Labs.

The Foundation Labs center on the art of Dalí. Macuare works with small teams of 10-12 people who are met at the door of the museum and taken on a three-hour journey into the gardens and through the galleries, using insights along the way to connect with business problems or topics of interest to the group.

The programs are tailored to each client although some of the modules —FourSight and LEGO® Serious Play, for example — are standard.

FourSight assesses the unique approach each client takes toward creativity.

Everyone goes through the same stages of creativity, but we do not all go through the different stages of creativity in the same way. “The way we go through the creative process is unique to each of us. And that’s what FourSight measures – what your proclivities within that process are,” says Macuare.

FourSight is the brainchild of Gerard Puccio, director of the International Center for Studies in Creativity at the State University of New York College at Buffalo. Nathan Schwagler, the co-founder (with director Hine) of The Dalí Innovation Labs, was a student of Dr. Puccio. Puccio’s research in the 1990s helped isolate four distinct stages that are required for a creative outcome.

“In the first stage, you are thinking about the problem, you are trying to clarify,” says Macuare. “So, what’s the problem? What do we know about it? This is the stage where you are doing exploratory thinking or you’re doing research. You are gathering data, you are formulating your problem statement. How might we better do x?“

The second stage? “We move to ideate. I think the big mistake people make when they think about creativity is that they think that the ideate state is all there is to creativity,” says Macuare. “That’s the stage people are accustomed to think about — brainstorming and sticky notes.

“Ideate is obviously where you come up with the ideas that might solve your problem statement. Certainly that’s an important stage, but ideating without already having clarified would be a kind of useless endeavor. If you don’t know what the problem is, how would you go about coming up with the solutions for it?”

The next stage is also one which often people ignore – develop. “That’s when you take the ideas that you’ve generated and you think hard about them in terms of how you can make them better. What’s good about them, what’s bad about them, how you might mitigate what might be problems with them because an idea is not a solution, and the development stage is really about taking an idea and making it a solution.”

The fourth — and final stage — is implement. “Implementation is where you actually put that solution into practice.”

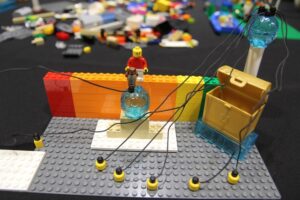

With LEGO® Serious Play, playing with LEGO bricks is serious business. For decades the LEGO company inspired children to “build their dreams.” In 1996 two professors at a Swiss business education school and the CEO of LEGO decided to give adults the bricks to play with and asked them to build three-dimensional models of their visions for future strategy.

“When you talk to someone about a scenario, such as a car accident they’ve been in or they’ve almost had, it’s very common for people to grab whatever implements they have on their desk and move them around so they can show you how everything was positioned or how things unfolded,” says Macuare. “That combination of a visual element with verbal utterance is a way to clarify and make yourself better understood and thus enhances communication. And that’s what LEGO Serious Play is based on.”

Picture suits sitting around a table with LEGO bricks piled in front of them. The facilitator asks them to build a model of their corporate culture and someone builds a prison with bars. Or they are asked to build a model of their boss and someone builds an alligator.

“People build models and then they share those models with their group. What makes it even cooler than just manipulating things on your desk is that there is a point in the session when people realize — just like artists do — that you’re not able just to communicate literal meaning — this is this car and this is that car. No, you’re able to communicate symbolic and metaphorical meaning through this visual representation,” explains Macuare.

The model of a small room with bars or an alligator become interesting metaphors that carry insights into how someone is thinking about their company’s culture. “People not only enhance communication, but they start to deepen communication. The more people share, the more trust and comfort they develop and then the deeper the conversations get and the closer you get to being able to really dig in with problems and come up with solutions,” says Macuare.

In August in addition to her work in the Innovation Labs, Macuare was named director of Community Programing. As in the Innovation Labs, she has had to come up with some creative solutions for an institution facing a severe budget crisis (The Dalí had to close its doors for three months last year) and where people still cannot meet on site as freely as they did in the past.

“We obviously couldn’t have our traditional opera programming,” she says, pointing out the danger COVID posed to singing in a closed space, “but the pandemic actually opened up an opportunity for us.” They couldn’t have the opera singer on the spiral staircase with people milling around below, but since the museum was for a while closed on Mondays and Tuesdays, they could have them sing in the empty galleries with the art.

“This is something they would never be able to do in normal times,” she says, pointing out that St. Pete Opera actually came up with a program of songs that interacted with the suite of prints that were on exhibit. “It was a perfect example of taking a negative and turning it into a positive.”

A perfect example of creativity at work.

thedali.org/programs/innovation-labs