By Margo Hammond

. . .

Celebrating Classical Players,

Conductors and Composers of Color

. . .

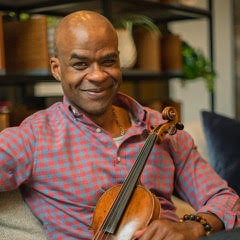

Black classical musicians — a world within a rarified world — have been in the spotlight lately, thanks to two recently published novels by Black violinist Brendan Slocomb.

Slocomb’s first novel, The Violin Conspiracy was a 2022 bestseller and has become a favorite book club selection, picked up by Good Morning America Book Club, the L.A. Book Club (watch its interview with the author here) and the AARP’s online Senior Planet Book Club.

. . .

The Violin Conspiracy tells the story of Ray McMillan, a poor Black young man who is drawn to play the music of Brahms and Beethoven. His mother doesn’t understand his obsession (she wants him to get a job to pay the bills), but his grandmother encourages his seemingly impossible dream by giving him the family “fiddle,” passed down from his great-great-grandfather who had been enslaved.

It turns out to be a priceless Stradivarius, a gift of a slave master. But just before McMillan is to play his violin at the prestigious Tchaikovsky competition in Moscow, the instrument is stolen. Who is trying to thwart this young Black man’s career? The Violin Conspiracy draws us into the mystery.

In his second novel, The Symphony of Secrets, Slocumb also addresses the subject of classical music and race. In that novel, a Black researcher discovers a shocking secret – the country’s most famous white composer’s works are not his. He stole them from a homeless Black woman who was a musical prodigy and passed them off as his own.

We usually associated such stories of “borrowings” if not outright theft of Black music with pop music (think Elvis and Eric Clapton), but setting a story of cultural appropriation in the classical music world is not so far-fetched. At last month’s performance of the Tampa Bay Symphony, Maestro Mark Sforzini told a real-life story of just such a “borrowing.”

The concert paired the music of two composers who were contemporaries, one white and one Black – George Gershwin and William Grant Still. In the third movement of Still’s Afro-American Symphony, which marries classical music with elements of blues (a tenor banjo is added to the full orchestra), there is a familiar riff which sounds a lot like the iconic Gershwin song, “I Got Rhythm.”

But it wasn’t Still who had borrowed from Gershwin, Sforzini explained to us. It was Gershwin who had appropriated the phrase from Still.

“Still was the oboist in the pit orchestra for Eubie Blake’s 1921 Shuffle Along, Broadways’ first all Black musical and a cultural sensation,” wrote TBS cellist Ruth Kern in the evening’s program notes. “One repeat audience member was up-and-coming songwriter George Gershwin. According to Blake, Still spiced up his part with a phrase he repeated at every performance that nine years later appeared in ‘I Got Rhythm.’”

. . .

Until 1950, Still’s Afro-American Symphony was the most frequently played symphony in orchestral halls. Now Still’s more than 200 works—or the works of Florence Price, another prolific Black composer of that period—are seldom played by major symphony orchestras.

Black composers are not the only ones missing, however, from classical music performance halls. Even more striking is the small number of Black players in the orchestra. According to a 2014 diversity study by The League of American Orchestras, an organization that represents both amateur and professional symphony orchestras across the country, less than 2% of orchestra musicians are Black.

. . .

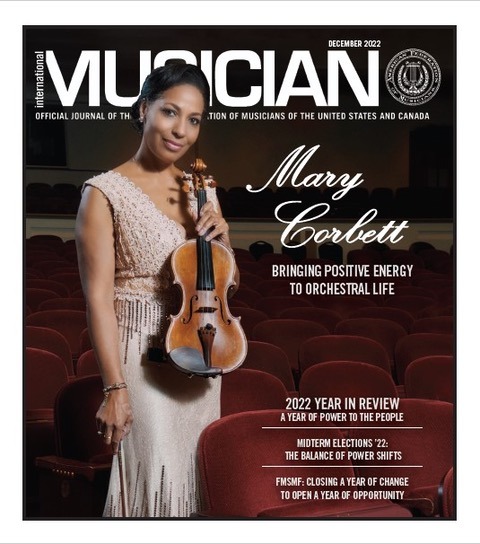

The first African American member of The Florida Orchestra — violinist Mary Corbett — joined in 1989. Now 33 years later, she is still the only full-time Black player in TFO. In between there have been only two other Black members – Demarre McGill, who played for a few seasons as principal flute (he now holds that position at the Seattle Symphony Orchestra), and Thomas Wilkins, who was the orchestra’s associate conductor in the ’90s (and now Principal Conductor of the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra).

“Other than that it’s been me, the only person of African descent,” Corbett told me.

I recently met up with Corbett in her butterfly-friendly garden in the backyard of her Woodlawn home in St. Petersburg to talk about that unique experience.

Lack of diversity in orchestras, she tells me, is not unique to TFO. “It’s a worldwide phenomenon.

Even the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, which plays in a tremendously Black-centric city, currently has only two Black members.”

The small number of Black orchestra members can’t be attributed to discrimination in hiring, Corbett adds. Since 1970, auditions for spots in major orchestras are blind, she explains. That is, musicians audition behind a curtain to assure that only the music and not gender or color determine the outcome. “They have even installed carpets to muffle any sound so recruiters can’t tell if it is a woman wearing heels,” she says.

“We’re not turning Black people away. I proctored several auditions between 2017 and 2020 – nationally, auditions on instruments such as the piccolo, violin and trombone and people of color weren’t showing up, at least not at The Florida Orchestra auditions.”

So how can orchestras encourage more interest in classical music in more communities?

According to Corbett, that interest needs to begin at a very early age — and kids need to be convinced that they can succeed in that world. Fortunately, unlike Ray McMillan in The Violin Conspiracy, her African American parents supported her early interest in classical music.

Corbett’s mother was a music and language major and her father sang with a barbershop quartet, so she always was surrounded by good music. “The only reason I am playing the violin is because my parents were able to make the decision to move to a northern white suburb of Buffalo, New York where they had a fantastic string program, a magnificent Youth Orchestra and somebody nearby who gave me private lessons.

“I had two parents who were encouraging and supportive who drove me to lessons — mom would sit through the lessons in the other room. It was a complete team effort to make this all happen.”

You can listen to Corbett tell her story here.

. . .

In addition to attributing her success to supportive parents, however, Corbett also credits a fellowship that she received just as she was beginning her career. During high school, she had studied summers at New York’s esteemed Meadowmount School of Music. She won a competition to play with the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra and she received a bachelor’s degree in violin performance from Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. But it was thanks to the Charles Revson Fellowship in 1985 that she was able to intern for two years at the prestigious New York Philharmonic.

“We started at the top,” laughs Corbett. For two seasons she was treated as a member of that orchestra, voted in orchestra meetings and went on tour. The only other Black person onstage was Jerry Ashby who was the assistant principal horn at the time.

“Every single week a magnificent soloist and conductor,” she remembers. “Zubin Mehta was the musical director. And when he wasn’t there we had the likes of Erich Leinsdorf, Kurt Masur and Leonard Bernstein. World class soloists, enthusiastic audiences, fabulous venue and a very livable salary. You couldn’t ask for anything more thrilling as a classical musician. I continued to play until 1993, feeling so part of it.”

Since that time, several other groups have emerged to work on helping orchestras better reflect the communities they serve. The most visible, says Corbett, is the Detroit-based Sphinx Organization, which in its 25-year history has invested more than $10 million in artist grants and scholarships serving more than 1,000 artists. A few years ago, Corbett attended the group’s annual global conference called SphinxConnect which showcases the organization’s Sphinx Competition Finals Concert.

“Seeing an orchestra made up of all Black people was life altering,” says Corbett.

. . .

Also championing diversity in classical music are the Chineke! Orchestra, founded in 2015 to provide career opportunities for Black and ethnically diverse classical musicians in the UK and Europe, and the Gateways Music Festival, a week-long event which began in 1993 in Winston-

Salem and is now held in Rochester NY to showcase performers and composers of color.

“Representation matters,” says Corbett. “Like the presidency of Barack Obama which has encouraged young Black people’s interest in politics, seeing someone who looks like them tells kids it’s possible.”

. . .

What about diversity in the audience at classical musical concerts? Even when the Tampa Bay Orchestra put a Black composer on its program, the audience for Sill’s Afro-American Symphony still was primarily white.

Corbett sighs. “Orchestras have trouble attracting any audience. Classical music itself is a very small niche. But if orchestras want to get Black people interested, they should look to familiar names.

“Last January we had very good attendance when we included a piece by Wynton Marsalis. Wynton Marsalis. Black composer, familiar name. Duke Ellington. Black composer. Familiar name.

“I think that’s the answer. Doing stuff people can hook on to. I don’t care if you have to play it every season on a loop. Play the same thing. That was the largest group of Black people I had ever seen in the audience.”

At least we are beginning to see Black directors, she adds, pointing to the recent appointment of Jonathon Heyward as Music Director of the Baltimore Orchestra. She was also heartened to see two edgy classical musical performances that speak directly to the Black experience, played recently at major venues.

On January 31, the Sphinx Symphony Orchestra, a professional all-Black and Latinx orchestra comprised of top musicians from around the country, performed a particularly moving piece at the Kennedy Center called Seven Last Words of the Unarmed.

The seven-movement choral and orchestral work by Black composer Joel Thompson sparked controversy when it premiered at the University of Michigan in 2015. It is inspired by the last words uttered by seven African American men killed by police or authority figures.

. . .

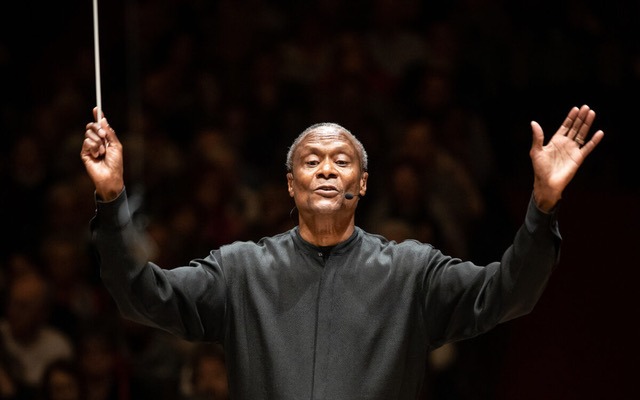

And this month, as part of the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s three weeks-long festival devoted to the exploration of “music as cultural witness,” former TSO director Thomas Wilkins offered a program of all Black composers – selections from Montgomery Variations, Margaret Bonds’ tribute to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr; William Dawson’s 1930 Negro Folk Symphony; and Anthony Davis’ You Have the Right to Remain Silent, a concerto for clarinet and orchestra with Anthony McGill as the soloist.

Davis wrote The Right to Remain Silent in 2010, inspired by an incident in the mid-1970s that still haunted him. Forty years before he won the Pulitzer Prize for music he was stopped by police on his way to a concert in a case of mistaken identity.

The soloist McGill, who is principal clarinet for the New York Philharmonic, sadly also once experienced the terror of being pulled over for the offense of “driving while Black.” You can watch McGill (whose brother Demarre was the flutist who used to play for TSO) in a virtual performance of the piece with the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra here.

. . .

Still, despite these signs of progress, Corbett admits, after 33 years with the Florida Orchestra, she had hoped to see more diversity in classical music by now. Bringing change to mainstream orchestras remains challenging, particular when that change touches on the subject of race.

Take for example the choice of orchestras across the country to play the national anthem at the start of every season, a practice that dates back to the feverish patriotism that broke out just after World War II.

“It’s an odd, and frankly inappropriate, custom,” argued classical music critic Scott Cantrell in a op-ed piece in the Washington Post back in 2015. “In a performance that celebrates global artistry, this is no place for perfunctory patriotism. The pomp and circumstance of a national anthem mercilessly clashes with the complex creativity of classical composers.”

. . .

Corbett also points to the anthem’s problematic third stanza which “actually glorifies slavery — literally. It’s tremendously offensive to people of color and people who are offended by the concept.”

“When the anthem was a hot-button issue,” says Corbett, referring to Colin Kaepernick’s decision to kneel during the anthem at football games to protest police brutality, “two of our conductors — our pops conductor and our coffee conductor — decided not to play it. It was their decision not to play it, and we didn’t play it. I was very appreciative that they were open-minded and considered letting the concept go.”

“Not playing the national anthem at classical music concerts does’t mean we don’t love our country,” she adds. “We don’t do it before the opera. We don’t do it before the ballet. Anywhere. Before Broadway shows? Before a Sarah Brightman concert? No. Why do we play it at classical music concerts?”

When I ask Corbett if she remembers her first day with the Florida Orchestra, she smiles. “Jahja Ling was on the podium. We were playing Prokofiev’s 5th Symphony. I was so impressed with the quality of the musicians. The winds. Some of the winds that were playing that day went to major jobs in Chicago, Boston and the like.”

And now?

“After over 30 seasons, we are like family,” she says, remembering what she calls her “satisfying time with her hometown band.”

“We’re not just colleagues. We’ve been together for such a long time. We have such a sense of history. We’ve lived our lives in this magnificent organization which allows us to create and be part of an incredible experience. I can’t believe I get to do it for a living.”

As Brendon Slobcomb says in The Violin Conspiracy – “Alone, we are a solitary violin, a lonely flute, a trumpet singing in the dark.

“Together, we are a symphony.”