By Margo Hammond

Ergo Sum: A Crow a Day, an exhibition at the James Museum which closed just yesterday, featured 365 original works of art by Canadian-born artist Karen Bondarchuk. It’s an exercise in repetition — for the artist, who painted a crow a day for a year to honor her mother who was suffering from late-stage Alzheimer’s – but also for me.

I went to the exhibit four times. Each time was a revelation.

Repetition isn’t my usual modus operandi. I very rarely re-read books, for example. There are too many out there that I want to delve into to have time to retrace my reading steps. When I see an exhibit, I usually move on to the next best thing.

Not this time. At first I thought I was returning merely to share the experience with others. But I eventually had to admit that it was the repetition itself that was catching my attention. The artist repeated the images to recapture the passing of time that her mother could no longer notice, but the repetition itself became a healing ritual for me not unlike the repetition of a mantra — and I imagine for the artist as well.

Creating an image of a crow every day for a year may seem like a limiting restriction, but by offering variations on the theme the artist gave herself — and eventually me — the freedom to explore a whole universe of memories. Not unlike the years of our own lives, the panels were filled with death and humor, joy and sorrow, the ordinary and the extraordinary repeated day after day. Viewed isolated, each portrait held some interest. Seeing them together was mesmerizing.

The first time I went to the Ergo Sum exhibit, I was by myself. I viewed the display of crows at random, walking back and forth, lingering over the images that spoke to me. I immediately took a picture of my “favorite” – a crow with his mouth full of letters.

But soon I found myself taking dozens more, each time convinced that, no, now this was my “favorite.” I seemed to be particularly attracted by the canvases that included letters and words (am I more drawn to words than images?). Two included quotes by Fernando Pessoa, a Portuguese writer I admire greatly. Another featured a crow with a cartoon word bubble over his head filled with a jumble of letters, a haunting reminder of how wordless and incoherent our thoughts are, even when we don’t have Alzheimer’s.

I was struck by how unique each painting was. Bondarchuk used a variety of painting techniques and colors. Every crow had its own personality — at times angry, at times humorous, at times friendly, at times menacing, at times contemplative, at times industrious. Some of the crows were very dead (literally on their backs with feet in the air) while others were very much alive.

The second time I saw Ergo Sum, I was with my husband. It was our anniversary and I thought he would enjoy seeing the exhibit. One of his first comments was to wonder why the curators had decided to hang the paintings as they did. Two groups of the paintings — small 7 3/4” x 5 3/4” panels — were mounted to the left and right of an opening to a long gallery space where more groupings of canvases were hung on either side. Were the panels displayed at random or in the order Bondarchuk had painted them? my husband asked. We pondered the question but came up with no answer so, like the first time I viewed the exhibit, we just wandered back and forth eventually taking them all in.

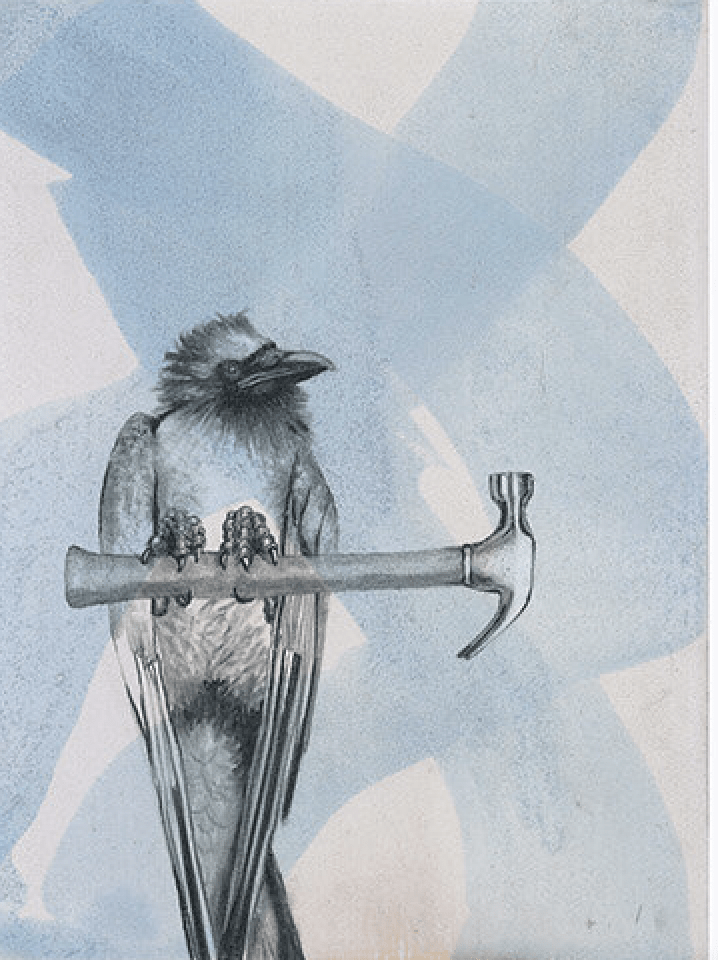

I pointed out my “favorites,” but my husband is a man who is the rare combination of an intellectual and a handyman and he was especially drawn to the crows shown with tools – one walking along toting a rake, another with a hammer in hand. He also was intrigued by the crow that looked like he was trapped in Hitchcock’s movie Vertigo.

Always more attentive to details than I, he also noted how often the artist posed her crows with ordinary objects falling from the sky – a drumstick, a frying pan, a book, a chair, a shoe, a nose plier. What was she trying to say in those portraits, we wondered. Neither of us had any answers, but thoroughly enjoyed their mixture of the wry and doom.

At my third viewing of Ergo Sum, I was with a couple — Art and Peggy Silvergleid — who had gone through a lot of strife these past months. Art just was emerging from grueling treatment for liver cancer, which seemed, thankfully, to be successful at last. Both were exhausted from the ordeal but ecstatic about the positive outcome. Both seemed happy to be out and about.

Peggy looked carefully at each painting, noting the different styles the artist used – texturing of paint, gold leaf. Art asked a familiar question – Which order do you think the works were painted in and were they hung in that order? I laughed and said my husband had asked the very same thing.

Peggy, determined to find the answer, stepped back and began to study the display, as if seeking a hidden order. Then she suddenly exclaimed, triumphantly – “Look. They’re laid out like calendar months.”

Looking at the pattern of each section, they indeed looked just like monthly wall calendars with the small paintings taking the place of blank squares for each day of the week. “All we have to do is find one that has 28 panels and that will be February,” she said. “Then we can figure out the rest.”

At that moment a museum visitor who was reading the exhibition’s wall text at the entrance to the long gallery space offered another clue. The text, she reported, says that Bondarchuk started her project in August. August 1, 2014 to be exact. “So this first group of paintings must represent August,” she said.

Excited, we all walked down the long gallery space, counting down the five sections along the left wall. September, October, November, December and January fell away like the calendar pages in an old time movie. Across from the January section on the opposite wall was a section with 28 panels. As Peggy said, that section was clearly February! So moving back up the walkway we counted March, April, May and June, arriving back at the entrance.

The section hung at the right of the entrance was obviously July, the end of Bondarchuk’s year of crows. All the months had clicked into place. Peggy had cracked the code of the paintings’ order of execution.

My final visit to Ergo Sum, with my friend Carolyn Nygren, took on a particular poignancy. Carolyn’s own mother had died of Alzheimer’s. The first thing Carolyn noticed was the varying hues of the paintings – some were full of bright colors while others were dark and muted. Did the brighter canvases represented Bondarchuk’s happier moments with her mother and the darker reflect the harder days she had dealing with the loss?

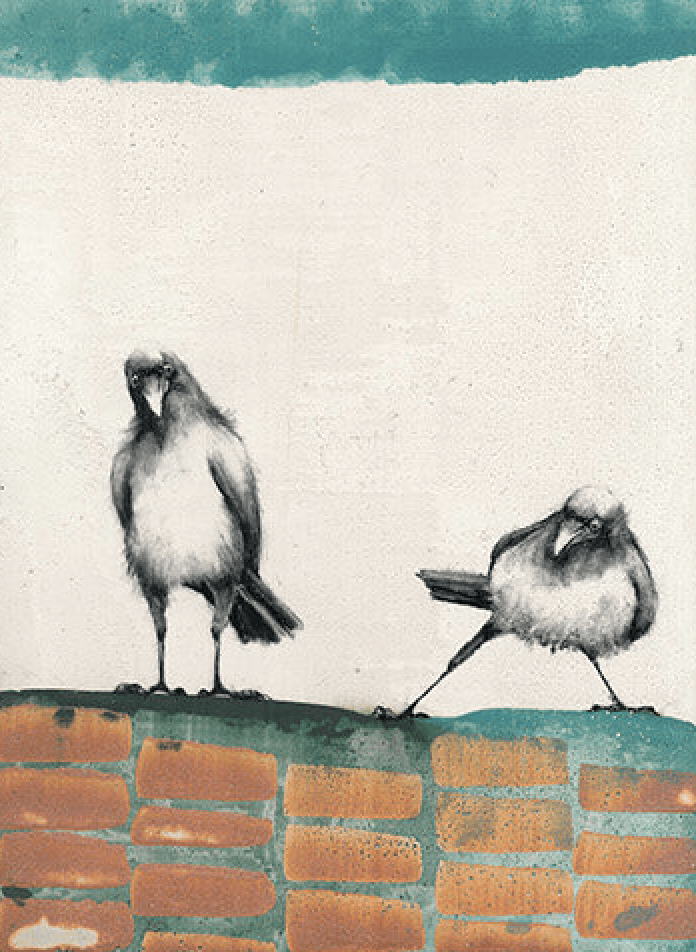

Carolyn also pointed to the many times Bondarchuk had chosen to include more than one crow in a painting. Did any of them represent mother and daughter? One clearly appeared to be a mother crow berating her offspring.

My friend reminded me that as we grow older, often the child, tasked with caretaking, has to become the adult as the parent reverts to childish behavior. “My mother was very difficult at times,” Carolyn confided.

Bondarchuk doesn’t provide much in the way of explanation of what was going on in her mind when she painted all these crows, as if she prefers to let us fill in our own memories and experiences of loss. Only a few of her comments were included in the exhibit’s wall text.

“The series is simultaneously a marker for my mother’s lost time and a constant and acute reminder of my own days, my life, and an attempt to signal visually the preciousness and individuality of each day,” she says. “Although the project seemed sober to me at its outset, quirky cheer and serendipity came to inhabit many of the panels.”

All the gessoed canvases in the exhibit were handmade by Bondarchuk. Preparing the canvases, she says, fittingly evoked for her the overwhelming labor and repetitious activities of motherhood. She had to cut the wood, prepare her own gesso from gelatin and powered limestone, build up layers on the canvas and sand between coats — and then, of course, actually create a new image each day.

She says she was marking the passage of time that her mother no longer seemed to recognize, but she also ends up reflecting our own relentlessly repetitious days.

Bondarchuk has often turned to crows in her artwork — usually depicting them in large scary sculptures lying immobile on the ground or looming at you from enormous canvases. For her, crows represent both the quotidian and the extraordinary – akin to the Buddhist notion of “ordinary magic.”

I wish I could have gone to Ergo Sum a fifth time with my friend Karen Pryslopski. I think Karen, who died earlier this year, would have loved this exhibit. She had a thing for crows, even once commissioning a large-scale painting of a crow from her friend Patti Yablonski. I always thought her interest in crows was odd because she was such a cat lover. But after my repeated visits to Ergo Sum: A Crow a Day, I realize that Karen’s embrace of both crows and cats had a kind of symmetry to it, representing the yin and yang of life.

Karen was the most balanced person I ever knew. She understood the importance of taking in all of life, the good with the bad. On one hand, she recognized that life wasn’t always going to go smoothly. When she was mad at her boyfriend and I asked her what annoyed her most about him, she would joke, “It’s all that breathing in and out. . . in and out.” On the other hand, she never failed to celebrate what she called her “crummy little life,” filled with small reoccurring pleasures like cooking and eating ice cream.

Repetition can be both exasperating and comforting.

After seeing Ergo Sum four times, I realize that its theme of repetition — and my repeated viewings of it — offered me a well-needed solace during this year of loss. It helped me gain an acceptance of loss along with an appreciation of what has not been lost – the day-by-day ordinariness of a crummy little life composed of both joy and sorrow, death and humor, toothbrushes, drumsticks, books, chairs and tools falling from the sky.

No matter whether we are conscious of our passing days or unaware of them, like the artist’s mother, we never know how and when and why death will hit us, do we? We just have to keep on keeping on, one crow a day at a time.

You can explore the work of Karen Bondarchuck here

You can find upcoming special exhibits at The James Museum here