By Margo Hammond

Seeing “I”

. . .

Is that selfie you just took a work of art?

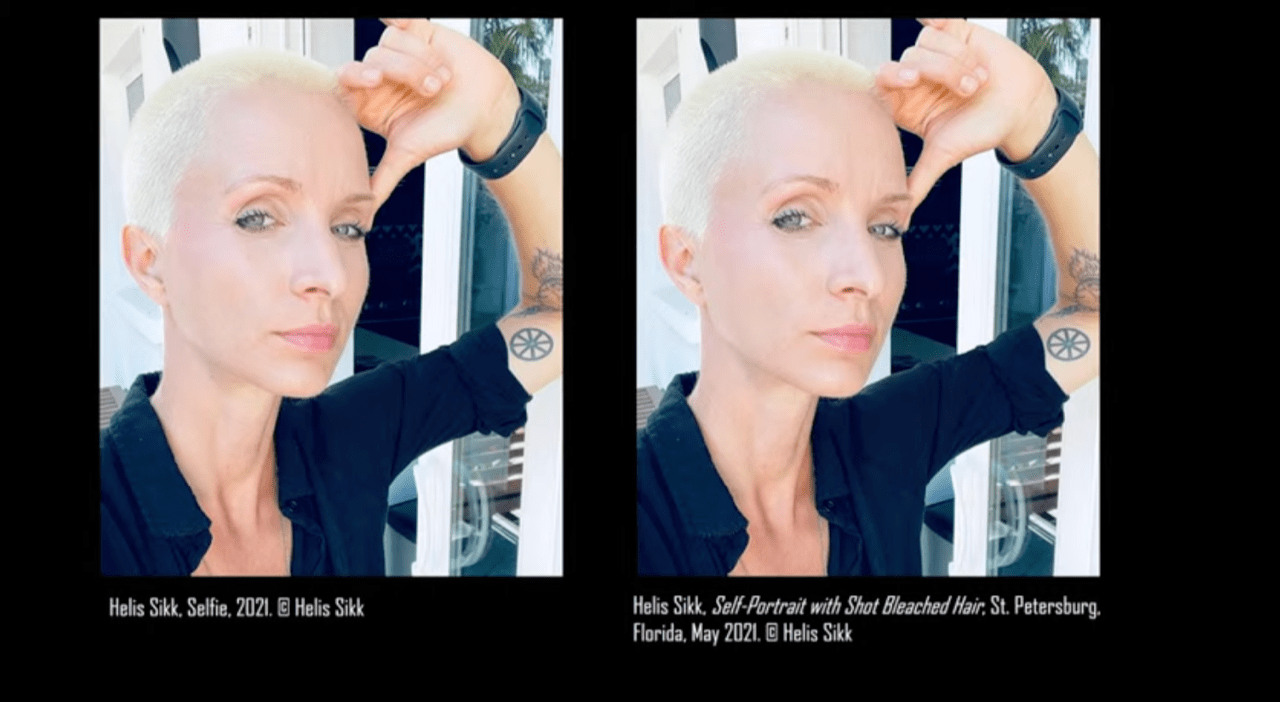

“Art historians and curators are going to hate me for this but, yes, selfies may also be self-portraits – and they both may also be art,” says Helis Sikk, a visiting professor at USF’s Department of Women’s and Gender Studies. “The self-portrait and the selfie both use technology to establish a definition of the self.”

Sikk was giving a lecture at the Dalí Museum in conjunction with the museum’s special exhibit The Woman Who Broke Boundaries: Photographer Lee Miller. Entitled Identity & Photographic Self-Portraits, you can watch the talk here.

Self-portraiture, of course, is nothing new. Pioneered by the Egyptians, Greeks and Romans, it came into its own during the Renaissance with the rise of individualism and the invention of really good mirrors.

“(Albrecht) Dürer invented the artistic self-portrait,” says Waldemar Januszczak in his engaging The Renaissance Unchained series available online. “Other artists had put themselves in their pictures before, but no one had made themselves the star of their own art as Dürer did,” inserting himself into engravings, paintings and altarpieces. In 1484 Dürer created his first self-portrait — himself as a teenage genius. He was 13.

Among Rembrandt’s paintings, etchings and drawings there are nearly 100 self-portraits, including his ruthlessly honest Self-Portrait at the Age of 63, painted just a few months before his death in 1669. More than two hundred years later Van Gogh was painting his own portrait — over 35 times — some say because he couldn’t afford to hire a model.

The form has been especially favored by women artists. From the Italian Baroque painter Artemisia Gentileschi, who represented herself as the personalization of painting, to contemporary Korean artist Yoo Hyun-Mi who blurs the line between photography, painting, sculpture and video.

See “10 Self-Portraits by Women Artists” – nearly every major woman artist has included self-portraits in her portfolio, some devoting their entire work to self-representation. Out of 143 Frida Kahlo paintings, 55 of them are self-portraits, many of them startling images of pain, both physical and psychological. “I paint myself because I am so often alone,” Kahlo famously explained, “and because I am the subject I know best.”

As Dürer learned early, self-portraits are a pathway to visibility — a key reason they are so attractive to those whom society has tried to render invisible. The form has been especially game-changing for gender non-conforming photographers, the subjects of Sikk’s talk.

The self-portraits of photographers such as E. Jane Gay (often described as the first American lesbian photographer) and Laura Aguilar (who specialized in photographing LGBTQ+, Latinx and obese people), for example, have played an important role in countering the default white male view of the world, Sikk says. “Pushing gender norms and roles, establishing visibility, challenging the politics of respectability, challenging whiteness, challenging colonialism in the art world, in the world, within their communities and outside their communities,” these self-portraits, sometimes uncomfortable to look at, have forced us to see these marginalized artists.

And now with the invention of mobile phones, anyone can participate. “Portraiture has been more democratized through selfies and social media,” says Sikk. “No longer reserved to gallery spaces and the professionalism world of artists, selfies have expanded the purpose that self-representation can have — from self-care to communicating your whereabouts. In those small moments, everyday people use those self-representations to push the boundaries of what we count as a human experience.”

Of course, most of the selfies we take — photos with friends (or with a hamburger we’re about to eat) — will never be mistaken for a Rembrandt or a Kahlo or an Aguilar. But selfies do spring from some of the same human impulses that move any artist to choose self-representation – the desire to be seen and to shape how others see us.

The selfies we take also tell us something about how we view ourselves — and how we want others to view us. When I looked over my own selfies, I was struck by how often my face was hidden — under a bowler hat that I found in my hotel room in Lisbon where the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa once stayed or under a straw hat during a summer vacation with my family.

In others, my face doesn’t appear at all. I took a selfie of my feet against a patterned carpet during a museum visit, one of my shadow when I went out walking during the pandemic and another of my hand holding my favorite pen when I was asked to illustrate my 100-Word bio for this journal.

What do those selfies say about me? I’m not sure. Perhaps that writers prefer to remain hidden behind their words? At any rate, Sikk inspired me to study other people’s selfies and self-portraits for inspiration for my next attempts at self-representation.

Luckily exhibits at three local museums offer plenty of opportunities to do just that. Here’s the tour. . .

. . .

Leepa-Rattner Museum of Art

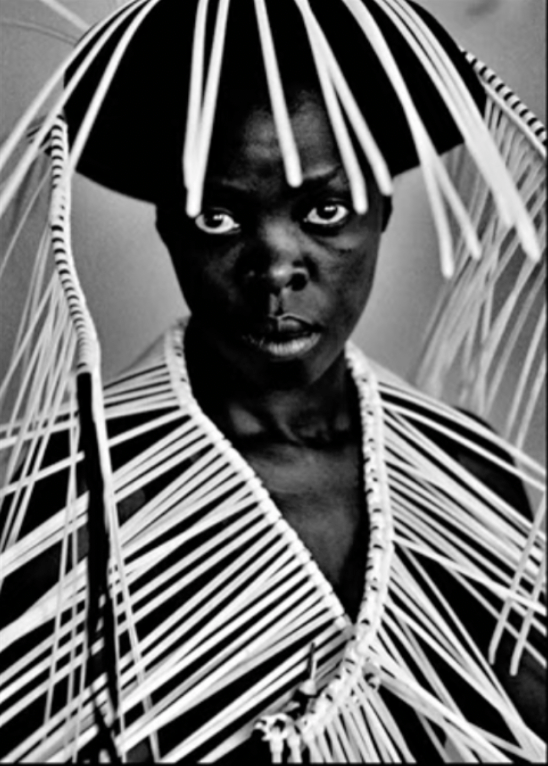

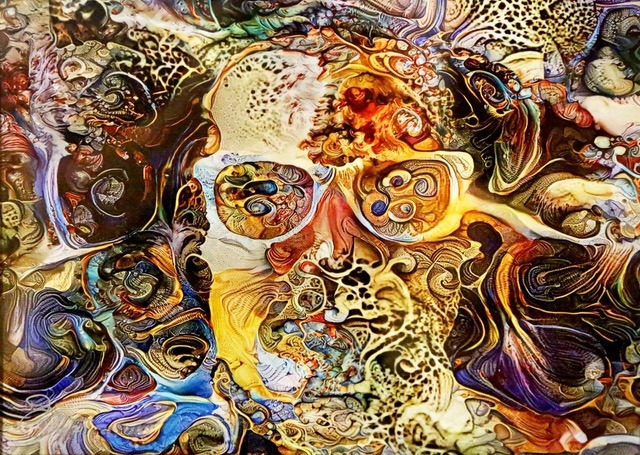

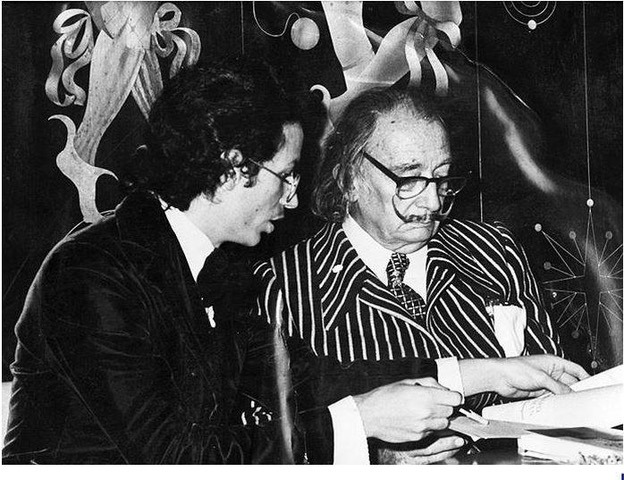

Louis Markoya: A Deeper Understanding invites you to go inside the mind of St Petersburg artist Louis Markoya, a protege of Salvador Dalí.. . .

Working and collaborating with Dalí for six years on 3D projects that included holograms, Markoya now melds “classical painting techniques and subject matter with the latest fractal and lenticular technology,” according to his website.

Among his self-portraits are Triumph of Intellect, done in the style of Dali’s self-portrait in The Ecumenical Council, and Self Portrait A Deeper Understanding, a lenticular print which can be seen at the Leepa-Rattner.

“Everything I’ve done is autobiographical,” Louis Markoya says in his talk on his exhibit at the Tarpon Springs museum which will be on display through February 6.

. . .

The Dalí Museum

thedali.org. . .

Dalí was the king of the self-portrait. The Spanish surrealist defined Soft Self-Portrait with Bacon, one of his most famous, as “an antipsychological self-portrait.” Instead of painting his soul, Dalí explained, he was painting only “the glove of myself.” Featuring a piece of bacon and an amorphous soft face supported by crutches on a pedestal that actually is labeled “Soft Self-Portrait,” the 1941 work is on display at the Dalí Theatre-Museum in Figueres, Spain.

The Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg also has a number of Dalí’s self-portraits on display, from his Self-Portrait (Figueres), which he painted when he was only 19, to his 1960 masterwork The Ecumenical Council, which inspired Markoya’s Triumph of Intellect.

The Dalí’s special exhibit of Lee Miller’s photographs, available though January 2, is another chance to study self-portraits. Included in the show is a color photograph marked Self-portrait (variant on Lee Miller par Lee Miller) c. 1930, a photograph entitled Self Portrait (with headband), which was published in American Vogue in 1933 – and the most iconic, which she took at the end of World War II.

The show describes the latter — Miller posing in Hitler’s bathtub — as “a self-portrait with David R. Scherman,” her companion during the war. The two friends, collaborating on setting up the shot, took turns in taking shots of each other in the tub in Hitler’s Munich apartment.

“I think she was sticking two fingers up at Hitler,” Miller’s husband Roland Penrose told the Telegraph. “On the floor are her boots, covered with the filth of Dachau, which she has trodden all over Hitler’s bathroom floor. She is saying she is the victor.”

Want to create your own provocative — and surreal — self-portrait? Check out the instructions on how to make a “morphing self-portrait” on the Dalí website to create an image where one half is you and the other is Dalí.

. . .

Museum of Fine Arts

mfastpete.org. . .

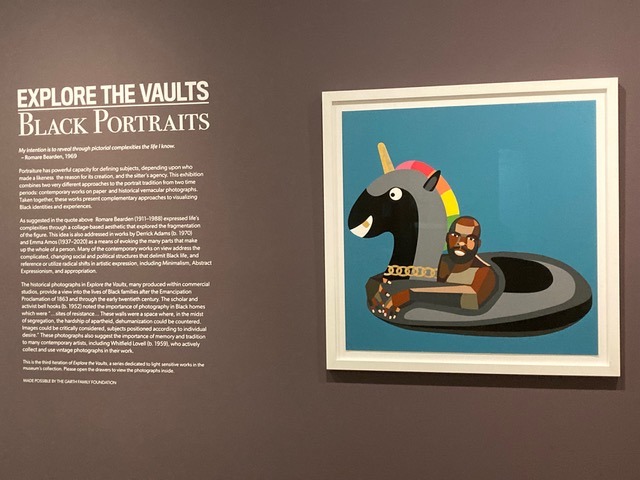

Three self-portraits are included in Explore the Vaults: Black Portraits, on display at the MFA through February 27.

Self-Portrait on Float (2019), a woodblock by Derrick Adams, is part of the artist’s Floaters series. Inspired by The Negro Motorist Green Book which helped Black Americans navigate travel during the Jim Crow era, the series focuses on the hard-fought moments of leisure for Blacks. In Self-Portrait on Float, Adams places himself on a black unicorn pool float.

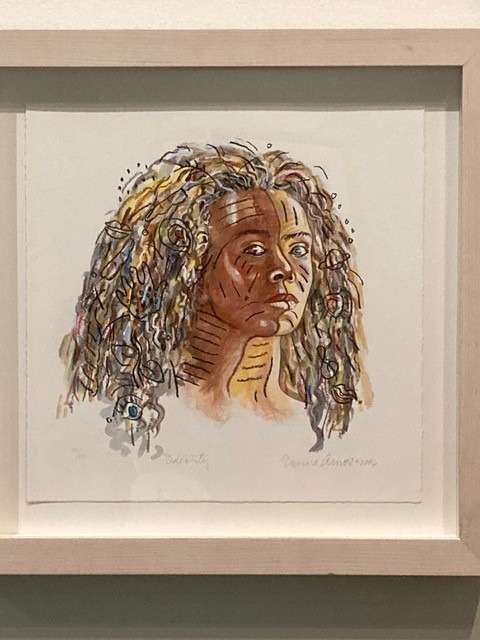

According to the exhibit’s brochure, “the complexity of personal identity is addressed in the works of Alison Saar and Emma Amos, who use self-portraits to consider their relationship to the African diaspora.”

Amos, who had firsthand experience of racial segregation, is included with a self portrait called Identity (2007). The digital print with hand lithography is part of Femfolio, a portfolio of prints by 20 feminist women artists. Addressing the complexities of biracial identities, this self-portrait changes depending on the angle at which you view the work, presenting as a unified individual or as two separate faces divided by the line down the middle of the face.

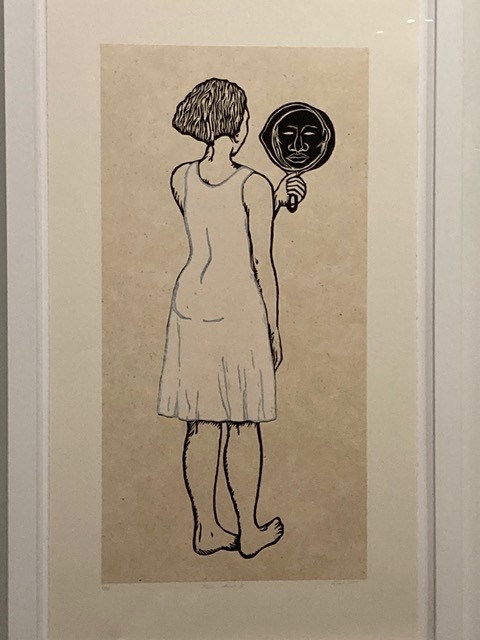

Saar’s work investigates ancestry, spirituality and multiracial identities. Her self-portrait in this exhibit is a woodcut depicting a figure holding up a frying pan to see her reflection. The title, Mirror, Mirror, Mulatta Seeking Inner Negress, refers to her own biracial identity.

Two self portraits are also included in the museum’s exhibit More Than Retro: Art Photography of the 1970s, on view upstairs through April 3.

Dianora Niccolini’s Vintage Self-portrait (1970s), is an experimental photograph made with a Color Xerox machine that shows both the photographer’s side profile and frontal face in colors not associated with skin tones.

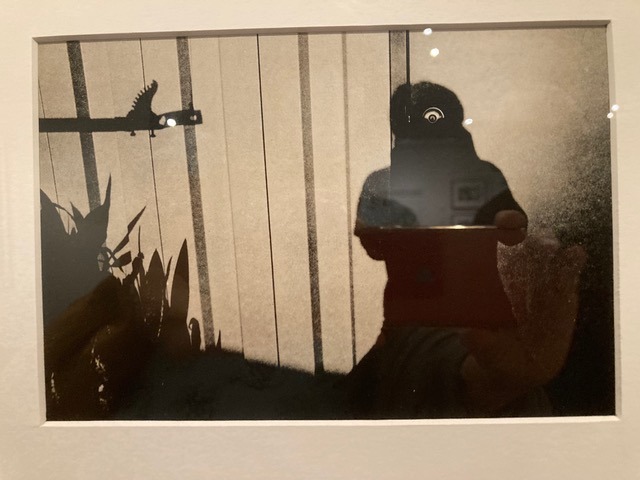

Oscar Bailey’s Me (1974), dubbed a “philosophical self-portrait,” shows the photographer’s shadow against a light building with a doorknob standing in for both his eye and his camera.

The MFA also has a painting in their permanent collection that may be a self-portrait.

Not currently on display, but available online here, The Clown Painter is by Italian painter Gino Severini. Severini, associated with the Italian avant-garde movement called Futurism, and its 1910 Manifesto of Futurist Painters, returned to figurative art in the 1920s.

“Perhaps this painting is a self-portrait, a mocking, autobiographical reference to the human condition,” concludes the museum’s notes on the work.

In 2018 the MFA hosted a photography exhibit called This Is Not a Selfie, which argued that the selfie, although a subset of the self-portrait genre, was “a vastly different enterprise than the self-portrait in the hands of an artists.” As selfies have become more sophisticated, however, and as artists make use of their mobile phones to create art, that distinction is fading.

To illustrate the close kinship between the self-portrait and the selfie, Sikk — in her talk at the Dalí — showed a slide of two images of herself side by side. The left one was marked Selfie. The right one labeled Self-Portrait With Shot Bleached Hair.

The images were identical.