September 2, 2019 | By Steven Kenny

We’re grateful to painter Steven Kenny, whose work combines surrealism with the techniques of Old Masters, for sharing his perspective on two very different exhibits on display at The Salvador Dalí Museum. . . exploring the influence of Goya in the 18th century and the futuristic technology of Augmented Reality.

Visual Magic:

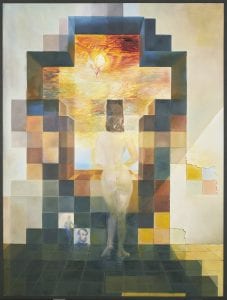

Dalí’s Masterworks in Augmented Reality

is on display through November 3

Find out more at thedali.org

The Los Caprichos print series

is on view through September 15.

The La Tauromaquia series is on

display September 21 – November 3.

Find out more at thedali.org

Salvador Dalí was voraciously curious and constantly experimenting. During the course of his career, he took every opportunity to push the envelope in ways that simultaneously challenged himself and his audience. He was not afraid to explore new ideas — especially if making them a reality required implementing new technology.

As a very young boy, he was attracted to anything that might alter and expand his perception of the world and present it in new ways. He loved peering through a crystal wine stopper to create a kaleidoscopic view of his surroundings. He was fascinated by the mysterious worlds seen within a stereoscope. He puzzled over exotic, unidentifiable scientific gadgets.

A short time later, after discovering painting and deciding to embark on his lifelong artistic journey, he began devouring all of art history. From the moment he first picked up a brush until the time he left art school, Dalí would master every form and style of painting known at the time. From there, with his technical skill sharply honed, all that was left to do was allow his imagination to run wild.

In the ensuing decades Dalí would create works by firing paint-filled bullets at his canvases. He invented a new mode of personal locomotion called an Ovocipede, and designed fashion, furniture, architecture, cutlery and jewelry.

He was inspired to consult and collaborate with influential scientists and thinkers of the day, even producing holograms shortly after that technology was invented. There was nothing Dalí wouldn’t attempt in his efforts to dazzle and astound both himself and the public.

So what would Dalí think of The Dalí Museum’s current exhibition Visual Magic: Dalí’s Masterworks in Augmented Reality?

Before we answer that, a little explanation of how augmented reality (AR) works may be helpful. First, you need to download the new Dalí Museum app to your mobile device (available in the Google Play Store). Once installed, you simply select a painting from the exhibition list provided, point your phone at that masterwork, and the image comes to life before your eyes!

Aspects of each painting begin to move while sounds play, drawing your attention to a variety of focal points. Once that short animation ends, the focal points appear as “hot spots” you can click on. Each narrated hot spot offers fascinating and informative insights into what you’re seeing, revealing Dalí’s sources of inspiration and artistic intentions.

It’s safe to say that Dalí would have been absolutely thrilled with this exhibition. Had this technology been available during his lifetime, he would have enthusiastically embraced and exploited it.

So much of his life’s work was devoted to getting us to question reality, question what we see, what we hear. He strove to push us off balance and lure us into his metaphysical realm. With the help of AR, this exhibition takes a giant step towards furthering his goal.

Visitors who are unfamiliar with Dalí and his art are given a key that will begin unlocking the mysteries that his works have to offer.

Before Dalí:

Goya – Visions & Inventions

It can be said that great artists stand on the shoulders of the great artists who preceded them. In the case of Salvador Dalí, the shoulders he stood on were many.

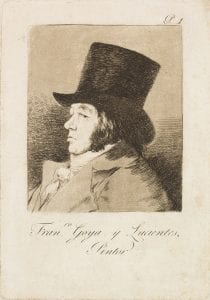

However, one important pair belonged to Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes who died at the age of 82 in 1828, 78 years before Dalí was born. In the current exhibition at The Dalí Museum, Before Dalí: Goya – Visions & Inventions, we clearly sense how high Dalí was lifted thanks to this earlier Spanish artistic giant.

The exhibition contains three of Goya’s oil paintings and a suite of 80 black and white prints, Los Caprichos, produced using a masterful combination of etching, aquatint and dry point. These powerful prints grab our attention and steal the show.

Although each work measures only about 11.5 by 8 inches, individually and as a whole their effects on the viewer can be profoundly unsettling. Like all great art, these images speak to us on a multitude of levels, often simultaneously: humor, horror, beauty, ugliness, sly innuendo, blatant articulation, realism and fantasy.

In Los Caprichos, Goya’s primary focus was on society’s dark tendency to turn on each other selfishly through methods ranging from subtle manipulation to open aggression. No one, regardless of status, religion, age or gender, was exempt from the artist’s critical gaze, including himself.

Goya never mentions anyone by name, but his subjects of ridicule are not disguised. We observe lecherous clergymen and avaricious aristocrats, we recognize superstitious peasants and gullible youths. To help get his message across, appearances are made by witches, goblins, anthropomorphized beasts and satanic demons.

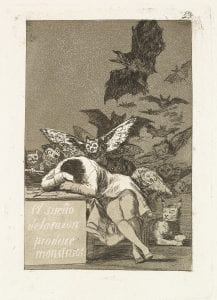

One print in particular illustrates the essential cause for all the turmoil. The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (1799) depicts the artist asleep at a desk, smartly dressed, his head resting on his hands. Behind and over him rises a menacing flock of nightmarish bats and owls with a lynx and black cat stationed behind his chair.

We could read this as a warning to keep our heads up and remain alert, and imagine everything will be fine if we can stay awake with eyes wide open. But eventually, sleep must come to everyone and frightful chaos ensues. We’re at the mercy of all that we struggle to keep subdued in the darkness of our subconscious. (No wonder Dalí loved Goya!)

Even though it occupies a place about midway through the suite, Goya originally intended this print to be first in the series. Metaphorically, it perfectly sums up the thread underlying the entire group: If we release our grip on reason and circumspection, we bestow our fate upon forces bent on their own greedy self-interest and self-preservation. This never turns out well. As true today as ever.

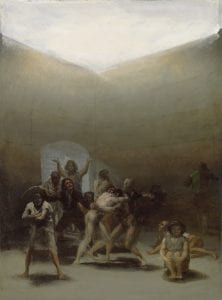

One of the three paintings on view is Yard with Madmen (1794). In it a group of men and women, clothed and naked, are seen wrestling, screaming, waving their arms. Is this chaotic asylum imaginary, or based on Goya’s own experience, or perhaps a theatrical performance?

We can’t be sure, but that barely matters. Our visceral experience of it is the same. The possibility of finding ourselves there is terrifying, yet we all carry this place somewhere inside us.

We sense that Goya knew exactly what he was talking about and he did. He’d seen and experienced it all. He spent many years rubbing elbows with royalty in his enviable official position as court painter to three successive Spanish kings, somehow managing to avoid offending any of them. He evaded scrutiny by the menacing eye of the Catholic Church and witnessed all around him the insanity of the Inquisition. He witnesses the carnage and barbarity of Napoleon’s Peninsular War. In his personal life, Goya and his wife Josefa saw only one of their eight children live to adulthood. He nearly died of a mysterious illness and was rendered deaf by it. There were bouts of depression and hallucinations.

Can we blame him for being cynical? His many professional triumphs and personal traumas qualified him to reveal through his art the heights and depths of life as he knew it.

In the margin of the preparatory drawing for The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, Goya scribbled, “[My] only purpose is to root out harmful ideas, commonly believed, and to perpetuate with this work of The Caprichos the soundly based testimony of truth.”

In many ways, this was Dalí’s goal, as well. He is quoted as saying, “One day it will have to be officially admitted that what we have christened reality is an even greater illusion than the world of dreams.”

Both artists knew that reality is both darkness and light. For them, to pretend that human existence is one thing to the exclusion of the other is to naively create an unsustainable mirage of self-deception.

Detailed photo credits here