April 20, 2020 | By Steven Kenny

Between Concept and Completion

How do artists move from concept to creation? In the case of visual artists, a physical sketch, or series of sketches, are often required to bring final form to an initial idea.

Sometimes an idea is so completely imagined in the artist’s mind that very little sketching, if any, is needed. In that case, the artist can confidently begin working directly on the final sculpture or painting. For plein air landscape painters working outdoors no sketch is required at all. The same goes for much abstract art which is meant to reveal evidence of the artist’s struggles, choices and changes of direction during the act of creation.

Sketches can take various forms. It is up to each artist to decide how best to visualize the result they are seeking.

Painters can work quickly in pencil or ink on paper creating small “thumbnail” sketches or more elaborate drawing. They can also work in paint to better envision the role color will play. Sculptors can make two dimensional sketches or work in three dimensions to produce small preliminary sculptures called “maquettes.”

In any event, the artist’s sketches or maquettes are not necessarily intended to be works of art in themselves and are often discarded after the final work is complete. Many do survive, however — and in the case of Old Masters, become sought after as valuable insights into the artist’s working methods.

Here is a sampling of how various artists used sketches to help them visualize the completed artwork.

Michelangelo (1475-1564) made many, many studies of the 300 individual figures in his Sistine Chapel frescoes. To transfer the sketches onto the wet plaster he made full-size drawings called “cartoons.”

The drawn lines were pricked with tiny holes and “pounced” with a small bag filled with powdered charcoal or red chalk leaving a dotted outline on the wall for the painter to follow.

J.A.D. Ingres (1780-1867) worked on a less monumental scale and made very detailed pencil drawings of his sitters to assure an accurate likeness before committing to working in oil on canvas.

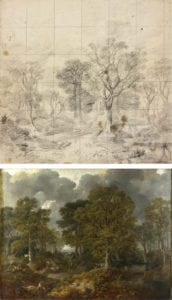

Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788) would venture into the countryside and make drawings on the spot while making notes regarding color.

After returning to his studio, he could use the sketches and notes to create his painting in comfort. You’ll notice a grid drawn over his sketch. This was used to transfer the drawing accurately, square by square, onto a larger canvas which had a corresponding grid drawn on it.

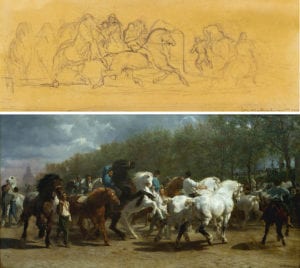

Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899) was known for large compositions featuring groups of horses or livestock.

Like Michelangelo, she had to make many individual sketches drawn from life to arrange all the elements in her lively paintings.

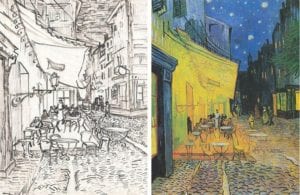

Not surprisingly, it’s easy to see similarities between an artist’s style of drawing and their painting technique.

This is true in the case of Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890). The marks he makes with pencil or ink on paper closely mimic the way he applied oil paint to canvas with brushes and palette knives.

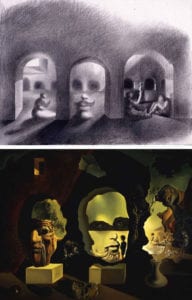

Sketches are very helpful in working through dilemmas when attempting to create a desired visual effect. Salvador Dali (1904-1989) took great pains to solve and refine the impact of his famous optical illusions.

A single preliminary sketch may bear only a vague resemblance to the finished painting — it being just one of many needed to arrive at a satisfactory composition.

Sculptors who work on a monumental scale must rely of others to engineer and fabricate their designs.

Claes Oldenburg (b. 1929) is known for making giant versions of small, everyday objects. He is one of many contemporary artists who pass on their sketches to others who have the physical means to bring their ideas to life.

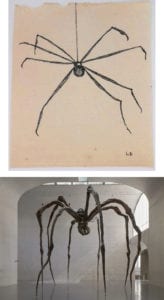

Another example is Louise Bourgeois (1911-2010). Spiders were a recurring theme during her long career.

. . .

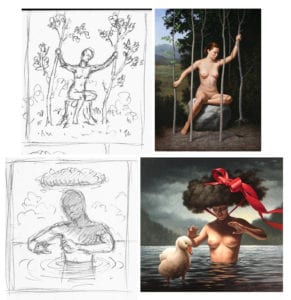

In my own creative process, a single rough sketch is enough to get the ball rolling.

I will use that as a starting point to begin painting, then add elements or make changes as I go without knowing exactly what the image will be when I decide that it’s finished.

These behind-the-scenes glimpses into an artist’s working methods can be just as interesting as the finished product, if we are lucky enough to view them.