Story and Photos by Emily Lee Stehle

. . .

In Dialogue: Unexpected Visual Conversations

Take a Second Look at Old Favorites

. . .

Through June 25, 2023

Museum of Fine Arts, St. Pete

Details here

. . .

I visit art museums to see the new opening exhibits and always plan time to see my “favorites,” works I’ve viewed in the past and return to see as “old friends.” The Art Bridges Collection, thanks to the generosity of philanthropist, arts patron and Walmart heiress Alice Walton, reveals a new light to view these friends.

Ms. Walton created the collection’s loan partnership to expand access to American Art all over the U.S. five years ago, offering “outstanding works out of storage and into other communities,“ says Stanton Thomas, Senior Curator of Collections and Exhibitions at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA).

His intent is to “use unexpected combinations (installing the visiting work with the MFA’s collection of world art) to inspire visual conversations, foster close looking and encourage deeper thoughts about the meaning and importance of art.”

. . .

. . .

The exhibit, In Dialogue, features almost a dozen major works from Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha NE that would have been kept in storage during a planned expansion, and a few on loan from St. Pete’s James Museum of Western and Wildlife Art. The project juxtaposes these mainly modern or contemporary works with the MFA’s older art masterpieces created perhaps a century or so ago. The works are scattered throughout the museum.

What’s so exciting about this exhibit is that Thomas and staff had the opportunity to select their loaned pieces from several groups of paintings and had time to plan their pairings for “interesting visual conversations so (our art) is seen in a new light.” Happily, MFA was granted their #1 unanimous choice.

The combinations bring together widely differing stylistic modes, historical periods and approaches, and narratives and commentary from the staff – not the usual look for those accustomed to seeing galleries hung traditionally, chronologically and according to the art historical canon. It’s a way of “shaking it up.”

Diverse themes range from gender issues, the environment, political figureheads and portrayals of Western history.

I found the contrast of the MFA’s master artworks next to these newer, modern, avant-garde pieces striking, unexpected, thought-provoking and delightful.

The Art Bridges Collection

. . .

I didn’t take notice where particular art was installed, so you may have to meander through the various rooms to find a particular piece. But docents are there to help guide you and can answer questions about the artwork.

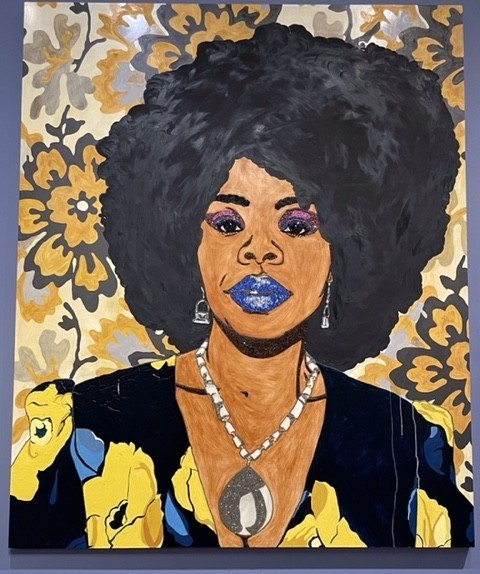

The most striking pairing for me was Jacques-Emile Blanche’s Contemplation (1883) with Mickalene Thomas’s ginormous Din, une très belle négresse (2012) in the European & American Art, 19th-21st Centuries Galleries. It is an interesting study of how women have been seen in society and portrayed over history.

I’ve always seen Contemplation as a very nice, pleasant painting of a serious young woman quietly sitting at a table, waiting. . . And now, right next to her is Din and a celebration with this larger-than-life portrait of a proud African American woman in her full finery and glory. Her blue lips glow. . . her light shines beyond the wood panel. She elicits a collective “Wow!”

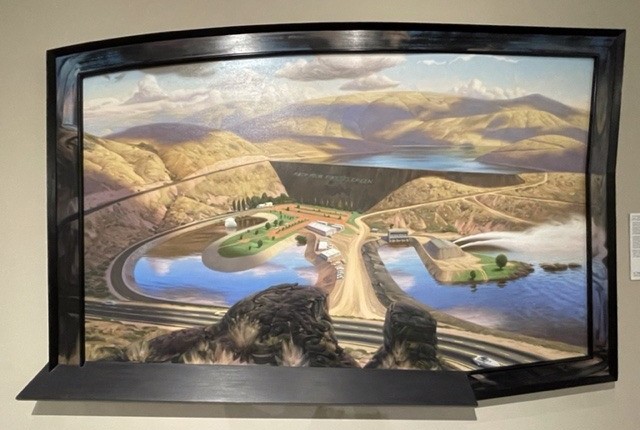

Thomas Moran’s Florida Landscape (1877) of the St. John’s River is exhibited with Lizard (1987) by Chuck Forsman. I saw this as a before-and-after cautionary tale of human impact on our environment.

Moran’s glimpse back into time offers a pristine time before Florida became a tourist destination. Forsman depicts the image of a Western expansive landscape marred by roads, building and dams. Note the unusual frame around Lizard. “I’m driving in my car. . .”

Manifest Destiny or the Westward Movement is the theme behind John Neito’s 1991 Not Necessarily the End of the Trail (after Fraser), from the James Museum. Nieto, a contemporary artist of Native American and Hispanic descent, based his painting on a sculpture, End of the Trail (1894) by James Earl Fraser. The sculpture shows a dejected warrior and evokes suffering, exhaustion and dispossession experienced by Native Americans of the time.

Neito was tasked by his grandmother to record “my people,” the museum commentary says, and used “rich, vibrant color to communicate a message of hope and resiliency.”

Not Necessarily the End of the Trail is paired with three Art Bridges works.

Portrait of Shaumonemusse (L’letan)

Bottom: George. Alex Bingham,

Watching the Cargo by Night 1854

One is Portrait of Shaumonekusse (L’letan), an Oto half-chief from what is present-day Missouri and Kansas by Charles Bird King. He majestically wears armbands, a grizzly claw necklace and a silver presidential peace medal, given to him as a symbol of friendship and allegiance with the United States.

Unfortunately, that changed. Decades after this work was completed, the leader’s ancestral lands were lost, treaties were broken and his people were forced to life on reservations, mainly in Oklahoma.

Watching the Cargo by Night (1854) by George Caleb Bingham depicts his documentation of the Westward Expansion and the importance of the Mississippi River. However, it happened only after the removal of thousands of Native Americans from their land.

Bottom: William de la Montaigne Cary,

Jim Bridger with Sir Walter Drummond Stewart, 1872

Ongpatonga (Big Elk), (1832-33) by Henry Inman was a principal chief of the Omaha People along the upper Missouri River. Renowned and respected among his own people and government officials as a man of great intelligence and foresight, he made treaties with the U.S. government and was often disappointed by their actions.

Jim Bridger with Sir Walter Drummond Stewart (1872) by William de la Montagne Cary shows America’s fascination with the American West. As a magazine illustrator, the painter made several trips to the territories documenting Western exploration and life. Jim Bridger was a renowned mountain man and wilderness guide and Stewart, a Scottish nobleman who traveled the West. The painting dates to several decades after their final excursion.

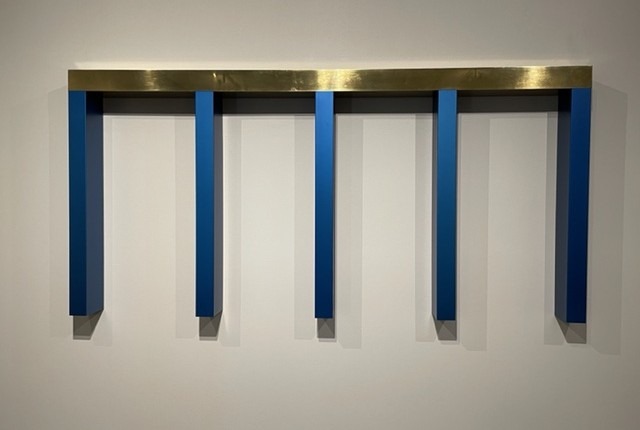

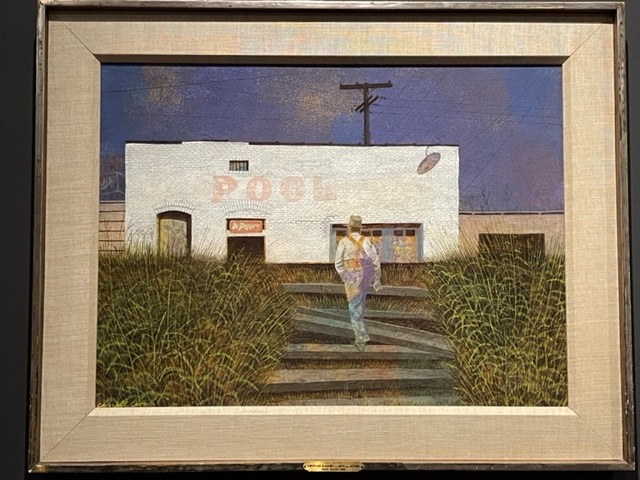

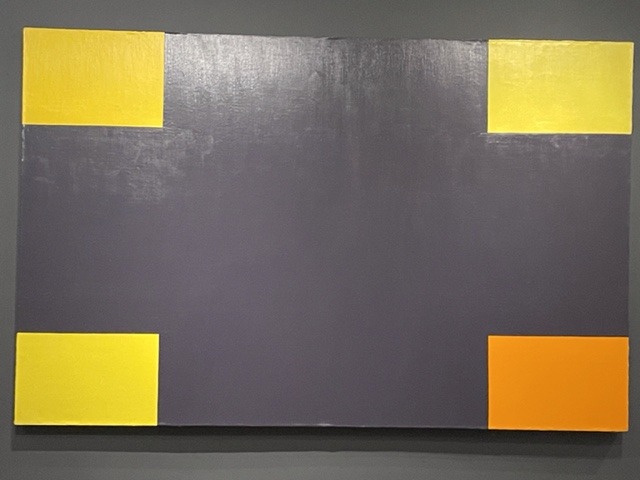

Contemporary artist Al Held’s Untitled (1964) was paired with Carroll Cloar’s Pool Room (1960) because of the similarity in their backgrounds. Both studied in Europe and the Art Students League in New York City and were interested in underlying political activism associated with Social Realist Art. The two painting were made four years apart.

Cloar works meticulously and was interested in, and most likely influenced by Jackson Pollock. The combination of Held’s monumental bold abstract work next to the small-town look and feel of Pool Room “explores how Americans tend to think of the second half of the 20th century as being in the realm of abstraction, though many artists continued to work in a realist mode,” says Thomas.

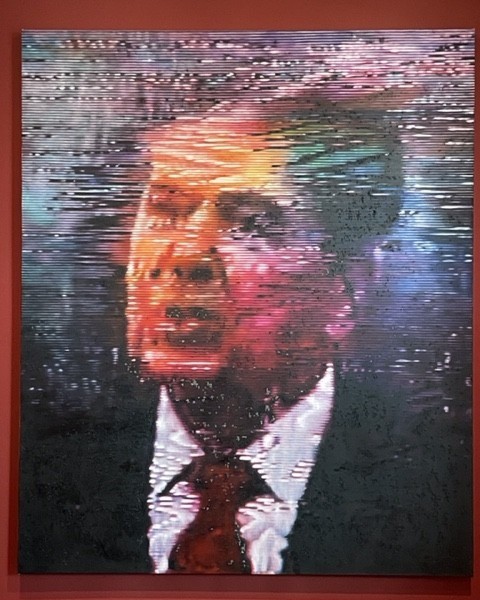

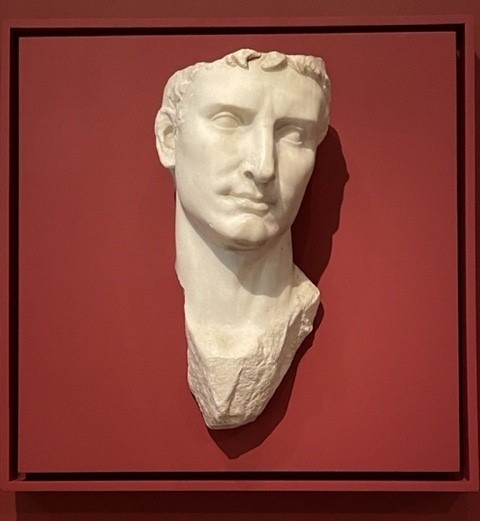

In the Ancient Art Galleries, you’ll find I Walked to Find You Gray (2015), an oil on canvas painting of Ronald Reagan by Russian American artist Kon Trubkovich. It looks like a broken image on a television screen while Reagan delivered his famous “Brandenburg Gate” speech. On the opposite wall is the Imperial Roman Head of Augustus (25 BCE). In Latin, “Augustus” means venerable, majestic or revered. Both leaders, politicians, appear somewhat battered, broken and not at full glory.

The pairing, says Thomas, “explores the idea of how time and memory alter our impression of political icons. . . and the enduring fascination we have with major public figures across cultures.”

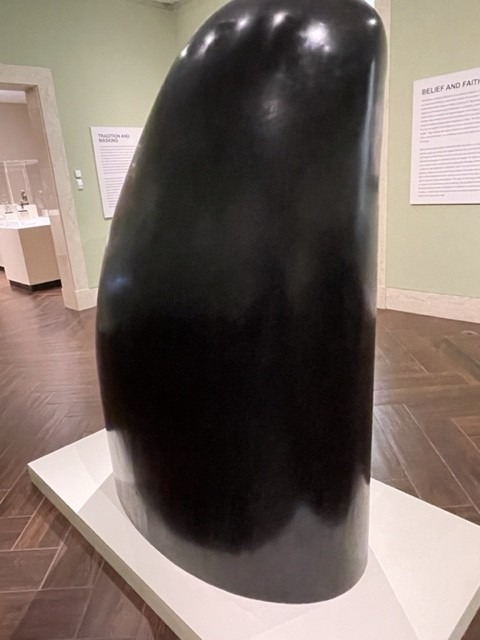

The most striking work on loan is Self…a hulking but elegant, somewhat mysterious black polished object that brought back to me the feeling of powerlessness and awe experienced by, of all things, the astronaut Dave from Stanley Kubrick’s classic epic 1968 sci-fi film, 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Placed in the African Art Gallery, the monumental Self (1978) by Martin Puryear, is paired with a very much smaller women’s society mask. Perhaps because they evoke a similar emotion of power – a mystery and a spirituality?

Curator Thomas says the combination speaks to the formative role that time spent by Puryear in Sierra Leone played in his artistic development while teaching in the Peace Corps.

Self is hollow, constructed like a boat out of polychromed red cedar and mahogany and stands taller than me. Puryear said the sculpture is “meant to be a visual notion of the self rather than any particular self – the self as a secret entity, as a secret, hidden place.

You’ll be very tempted to touch, but please don’t! Walk around it. Let it silently speak to you.

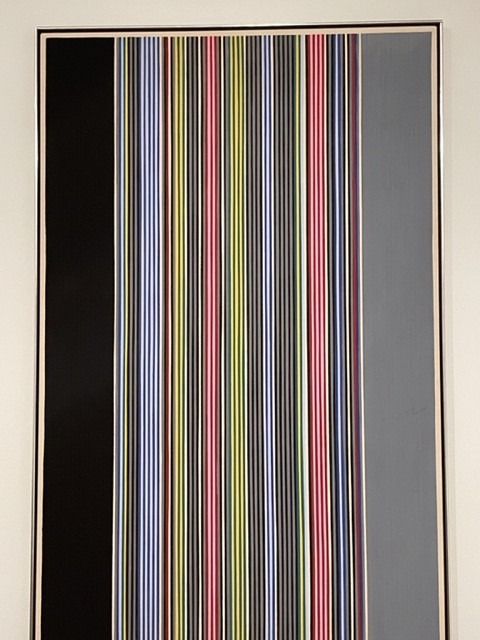

Geometic Abstraction

Hard-edge colorful stripes. It’s said Gene Davis was deeply influenced by music. He wrote in 1975, “Instead of simply glancing at the work, select a specific color and take the time to see how it operates across the painting. Enter the painting through the door of a single color, and then you can understand what my painting is all about.”

I think he was deeply influenced by poetry and a sense of cadence from music.

Robin Bruch’s work has a softer edge, a painterly approach to abstraction using swaths of color and brushstrokes. She studied at Vermont’s Bennington College and began working in ceramics.

I see some color, the color of soft matte glazes in fact, in this untitled work. Painter and writer David Reed said Robin “[Bruch found] a way to discover new possibilities, ways to re-invent painting.”

. . .

If the MFA’s goal in presenting In Dialogue was to inspire, educate and breathe new life into “old favorites,” I give them full kudos. They did it quietly, but spectacularly. I’ve gone back to see this exhibit two more times, returning one time with friends.

. . .

Museum of Fine Arts

255 Beach Drive NE

St. Petersburg FL 33701

Hours

10 am-5 pm Tuesday, Wednesday, Friday and Saturday

10 am-8 pm Thursday

noon-5 pm Sunday

727-896-2667

mfastpete.org

. . .

. . .