at USFCAM

Through December 1

Free

USF Contemporary Art Museum

Details here

Native America: In Translation at USFCAM is an exhibition of photography by nine contemporary artists presenting tribal peoples not as anachronisms, but as trendsetters on the forefront of culture.

The exhibition, organized by Aperture, evolved from the nonprofit publisher’s issue 240 titled, Native America, published in 2020 – which featured essays and interviews portraying contemporary Indigenous art and artists.

The issue was edited by Wendy Red Star, who also curated Native America: In Translation. Sarah Howard, Curator of Social Practice at USFCAM says the artists in the exhibition, “pose challenging questions about identity and heritage, land rights and histories of colonialism – probing the legacies of settler-colonialism, and photography’s complex, and often fraught, role in constructing representations of Native cultures.”[1]

The exhibition effectively de-homogenizes what has become the catch-all misnomer ‘indian’ by representing a variety of Indigenous peoples of the Americas.

Take a virtual tour here

Photography has had a fraught relationship with the Native American identity because photographers looking to depict a disappearing race in the mid-1800s and early 1900s were oftentimes too ready to depict Indigenous peoples as primitive, racially distinct, and vincible.

Red Star points out that citizens of her tribe, the Cree, who were photographed by the infamous Edward S. Curtis in the early 1900s, were familiar with the medium of photography and despite having been misrepresented, maintained their agency.

“In my community, we had been photographed a lot by the time Curtis came. So, we knew what the deal was, and a lot of the time we wanted money,” says Red Star.[2] “The sitters were like, ‘Give me some money and we’ll have our portrait taken.’”[3]

Marianne Nicholson, an artist in the exhibition, adds, “I don’t think our people who were participating in being photographed were completely unengaged. It wasn’t necessarily a one-way relationship. I think our people were certainly aware that they could utilize these things for their own purposes.”[4]

As artists working in the medium of photography, the Indigenous people included in Native America: In Translation, as well as its curator, are utilizing their agency to distort what’s traditionally been seen through a Euro-American lens.

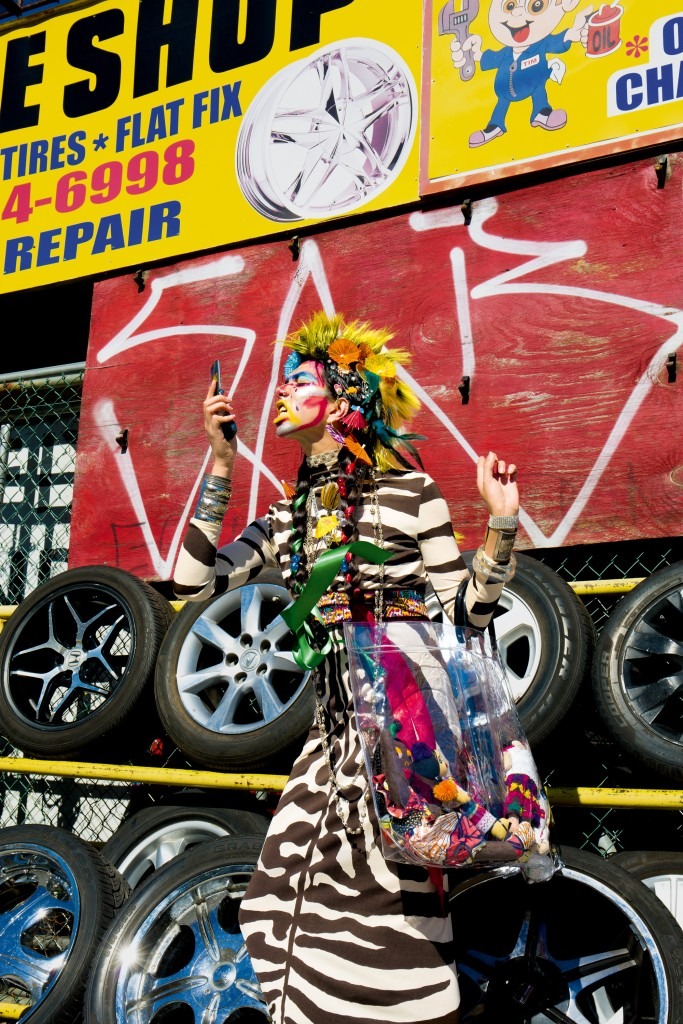

Upon entering the USF Contemporary Art Museum on the Tampa campus, viewers are greeted by life-sized self-portraits by Martine Gutierrez depicting the artist in various fashionable outfits. They’re photographed on a white background and in colorful locations like a fashion magazine’s editorial shoot, and were compiled in a 124-page magazine titled, Indigenous Woman (2018).

As a transgender woman, Gutierrez explains the impulse behind the series – representation. “No one was going to put me on the cover of a Paris fashion magazine, so I thought, I’m gonna make my own.”[5]

Queer Rage, That Girl was Me, Now She’s a Somebody (2018) shows the artist in heavy, cake-like makeup, an ornately floral patterned dress, lots of gold bangles and rings, and a necklace of red and gold feathers. She’s reclining supine on top of a brightly colored quilt depicting exotic birds and flowers, and has sunflowers nestled around her.

The polychromatic, neon-like color palette of the photographs reflect the traditional patterns and dress of the Guatemalan Indigenous peoples, including the Maya and Xinca, that have been appropriated and aestheticized by major brands. Gutierrez re-appropriates such fashionable patterns for Indigenous Woman, and presents herself as the idyllic model to be imitated.

The main gallery has artworks on view that represent a variety of photographic forms including black-and-white prints, color prints, mixed-media collages and a backlit projection.

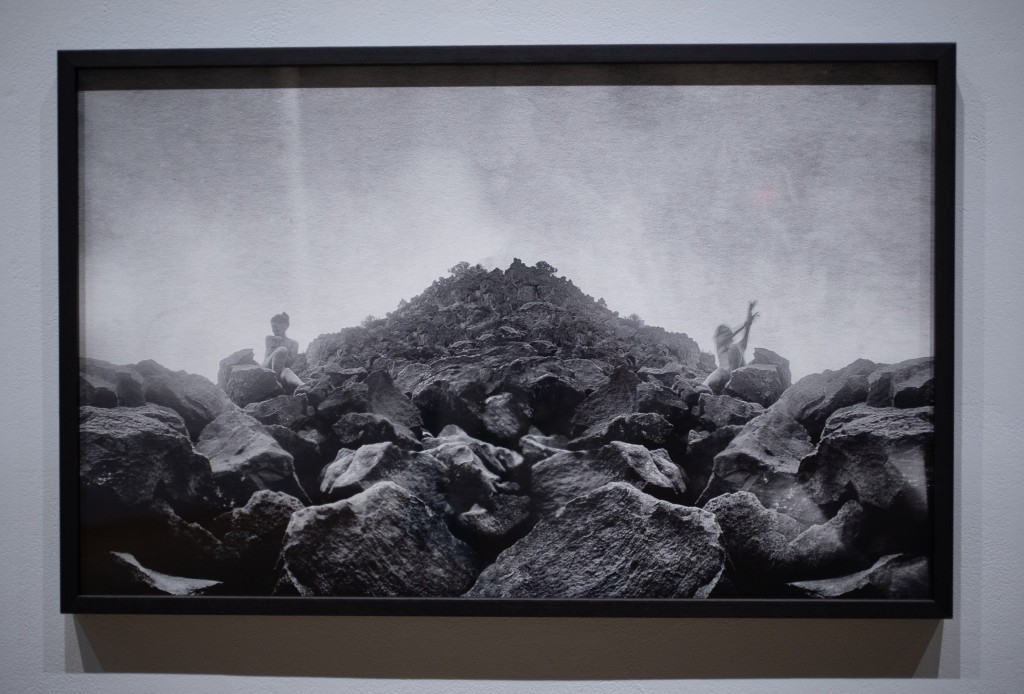

Koyoltzintli’s monochromatic depictions of models in the deserts of New Mexico interpreting the myth of the Sky Woman are presented alongside Naliqutaar Jacqueline Cleveland’s vibrantly saturated snapshots of her family and homelife in Quinhagak, Alaska.

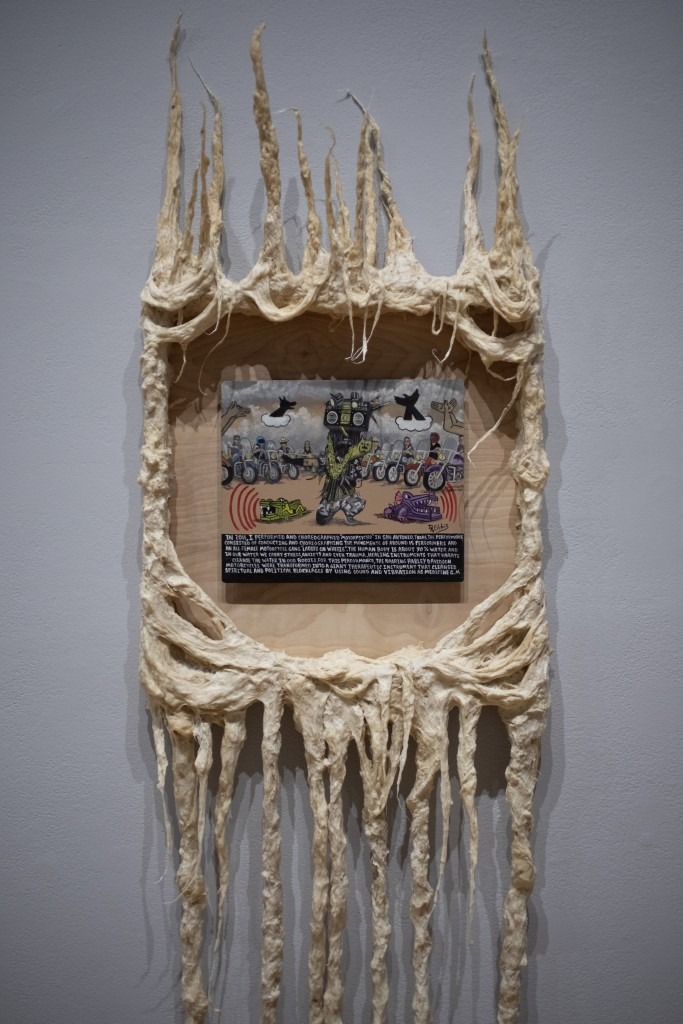

Rebecca Belmore’s staged portraits, printed larger-than-life, make an impact from afar – whereas the small, elaborately painted collages by Guadalupe Maravilla draw you in for further inspection.

In the middle of the main gallery, Marianne Nicholson’s artwork made of etched glass hangs from the ceiling and projects a large photographic image framed by pictograms onto the floor as shadows.

The photographic image is of Musgamakw Dzawada’enuxw children who Nicholson knew as elders. The image is from a time when they weren’t allowed to practice their customs—with one exception. “At the time this photograph was taken, our potlatch was banned by the Canadian government – it was outlawed,” says Nicholson.[6]

“So, the only way they were able to wear their regalia that you see them wearing, their button blankets and their headpieces, was because our people proposed to do a celebration for King George V, and, because of that, they were able to pull out their sacred regalia, put it on, and be photographed in it. This was them appropriating European forms of celebration in order to perpetuate their own traditions which were being suppressed by the colonial government.”[7]

According to the traditions of Musgamakw Dzawada’enuxw, the designs and patterns on the regalia tell stories of specific places and events, thus serving as land titles.

As such, appearing on the ground as shadows upon which viewers walk, the projected image serves as a reminder that these lands were stolen.

The back hallway and the side gallery feature collages and enlarged Polaroids created by the late Kimowan Metchewais, whose archive was coincidently located where Red Star was conducting research.

“When I did my Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship, I had not realized that that is where his archive is. So, I was thrilled to go through his Polaroid images, some of the journals, and when Aperture approached me, I said, ‘We have to have Kimowan,’” says Red Star.[8]

Cut Hair (ca. 1998) is a diptych of two enlarged prints of Polaroids, arranged vertically, that show the artist facing the viewer with long, black strands of hair flowing all the way down to the floor.

The diptych has an interrupted temporality similar to David Hockney’s joiners in that we see two moments spliced together in the upper frame and a disparate moment with a new perspective in the bottom frame.

On the adjacent walls are multi-panel artworks by Duane Linklater and Alan Michelson. Linklater’s piece is a several-panel collection of digital collages showing folded pages and printouts of a 1995 issue of Aperture that featured Native artists.

Michelson’s six-panel series shows maps of the Iroquois nation projected onto a white bust of George Washington, who in 1779 while he was a General, invaded Iroquois in Upstate New York.

In the corner of the gallery is a video by Michelson with footage of Native veterans from the Battle of Greasy Grass, also referred to as Custer’s Last Stand, riding horseback in a parade in 1926. The video is projected onto a red blanket arranged in quadrants in the clockwise manner of a Lakota winter count.

Native America: In Translation is emblematic of today’s institutional movement to represent Indigenous peoples, and of how Indigenous curators and artists are reclaiming the agency their ancestors weren’t afforded during colonial times.

As Marianne Nicholson says, “In the past, these institutions, and the medium, have been oppressive to Indigenous people. But in a contemporary context, now, Indigenous people like Wendy [Red Star], in terms of putting exhibitions together, who are allowing certain voices to come through are then allowing that agency to emerge institutionally.”[9]

This movement allows for Native Americans to be increasingly represented on the walls of contemporary art museums, not just as artifacts in dusty dioramas.

Native America: In Translation

Through December 1

Free

USF Contemporary Art Museum

4202 E. Fowler Ave

Tampa FL 33620

usfcam.usf.edu/CAM

Hours

Monday-Wednesday 10 am-5 pm

Thursday 10 am-8 pm

Friday 10 am-5 pm

Saturday 1-4 pm

[1] Institute for Research in Art USF, Native America: In Translation Online Conversation, YouTube, https://youtu.be/VuhmHLh4PX0?si=SunxvZnTpRDxy56B, October 4, 2023, 4:20.

[2] Native America: In Translation Online Conversation, 1:01:28.

[3] Native America: In Translation Online Conversation, 1:02:11.

[4] Native America: In Translation Online Conversation, 1:01:01.

[5] Nadia Rivera Fella, “Indigenous Woman” Aperture 240, Fall 2020, 54.

[6] Native America: In Translation Online Conversation, 18:57.

[7] Native America: In Translation Online Conversation, 19:48.

]8] Native America: In Translation Online Conversation, 34:02.

[9] Native America: In Translation Online Conversation, 45:02.