as Sculptural Works of Art

Through June 24

Ringling Museum, Sarasota

Details here

Michelangelo once said, “Every block of stone has a statue inside it and it is the task of the sculptor to discover it.”

Mountains of the Mind: Scholars’ Rocks from China and Beyond at the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art in Sarasota is an exhibition of rock sculptures from China, Japan, South Korea and Italy.

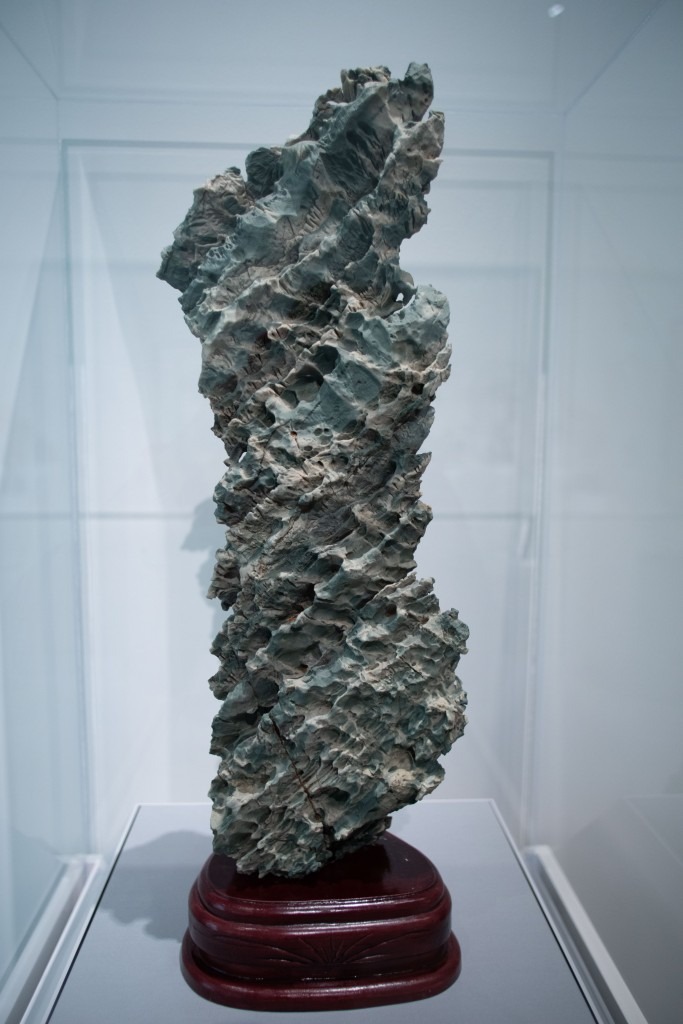

The sculptures, called scholar’s rocks, are marvelously abstract and colorful formations with porous cavities and jagged edges.

They’re presented in dramatic positions where they appear to the imagination as cresting waves, extraterrestrial terrains, and miniature dioramas of stalactite-ridden caverns.

Mountains of the Mind tasks the viewer not to discover the statue inside of these rocks, but to appreciate them as sculptures themselves.

Appreciating and cultivating rocks and beautiful stones as works of art has been a tradition in China for many centuries. Scholars started collecting aesthetically pleasing stones, known as gongshi, which means ‘spirit stones,’ during the years of the Song dynasty (960-1279).

The catalog states, “Because of their association with literati culture across East Asia, they are called ‘scholars’ rocks’ in English.”

The exhibition’s title, Mountains of the Mind, obliquely recalls Macbeth’s soliloquy, “Is this a dagger which I see before me. . . or art thou but a dagger of the mind, a false creation. . . ?”

The rocks’ abstract forms in the exhibition beg the question, ‘Are these formed naturally?’ They’re so ornate and seemingly delicate, like Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne (1622-1625), that it’s nothing short of astounding that they even exist, much less are created without the talent or proficiency of a master sculptor.

So, are they, as Macbeth puts it, a false creation?

The exhibition’s catalog reads, “In the process of becoming scholars’ rocks, they may be cut from bedrock, trimmed, carved, polished, inscribed, and finally mounted in a custom-made stand at an angle that enhances their visual appeal.” They’re creations of nature’s hand in collaboration with a cultivator’s pruning.

“Some of them are pretty natural,” says Curator of Asian Art at the Ringling Museum, Rhiannon Paget, “but a lot of them are enhanced. That’s part of the art form.

“Especially, in the case of Taihu rocks, we have records going back that describe the harvesting, or farming — it’s often translated into English as ‘farming’ these rocks.

“There were farmers who, for generations, would cut rocks from the bedrock, and if they weren’t ready to be sold they would do some enhancements, maybe drill some extra holes, and throw them back into the lake. Then, the grandson, in a few decades, would pull it up and the form would have been softened.

“The process is an interesting combination of nature and culture. It’s kind of akin to gardening, or Bonsai, where you have to have the long view.”

The exhibition consists primarily of scholar’s rocks from the private collection of Nancy and Stan Kaplan. “They started collecting scholars’ rocks after Stan purchased their first one at an antique fair,” says Paget, “he moseyed on down there, on the weekend, and called Nancy saying he’d found something and bought it, so he brought it home in his backpack.”

The wooden stands for each rock are custom-made for that particular sculpture. “For one or two of them,” Paget says, “Stan actually made the base himself.”

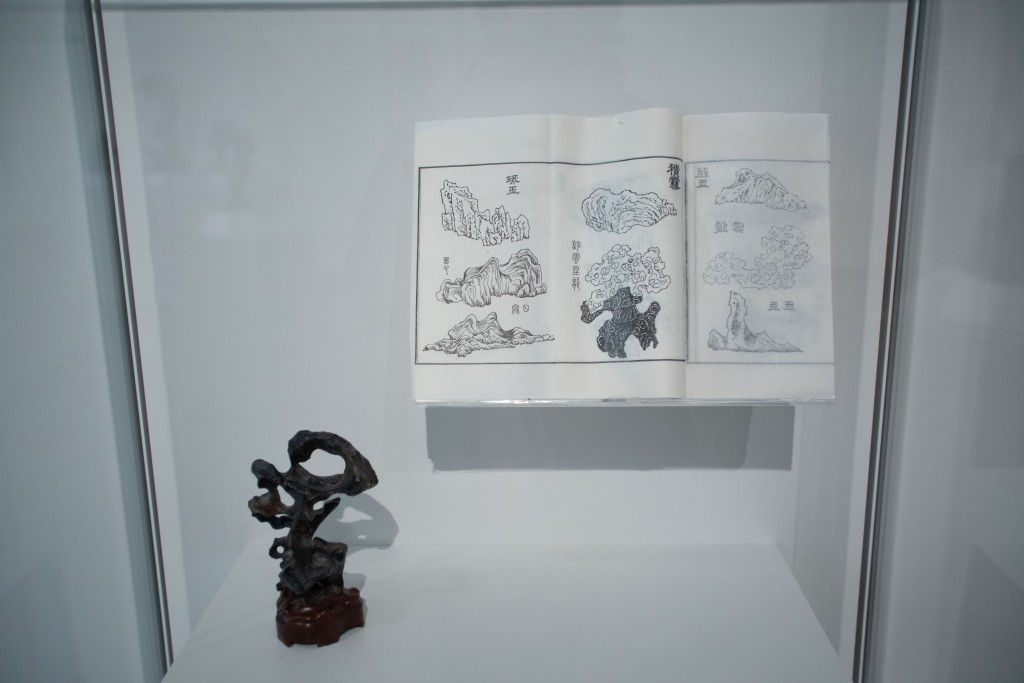

There are also illustrations and paintings depicting the abstract forms of the scholars’ rock on view both from the museum’s permanent collection and some on loan from the Dongguan Lou Collection. “

The woodblock print by Yoshida Tōshi, we purchased for the show, as well as the two paintings by Howie Tsui, and the other paintings are from our local collector,” says Paget. “We’re going to rotate the works on paper over the course of the exhibition.”

In general, describing the shape and appearance of the scholars’ rocks in terms of their representational capacity is like trying to tell someone you see a horse head shape in a cloud – as soon as you pinpoint something it shifts into abstraction.

But the best real-world corollary for what they look like may be fossils of dinosaur skulls that have been weathered and eroded over millennia.

With their unrecognizable crevices and grotesque orifices, their appearance even gives the impression that if it were discovered that they were alien bones it wouldn’t be much of a surprise.

“Once you see something in a rock, it’s hard to not always see that thing,” says Paget, “and some viewers really want the rocks to look like something else. Certainly, there’s a whole history of that in China where they would imagine the rock as an eagle form or a dragon form.

“Some of the rocks in the exhibition are clearly meant to be that kind of form, but I left that off of the labels for the titles because I wanted the viewers to experience them how they experience them, let them recognize what they recognize – or don’t recognize anything and just enjoy the abstract form of it.”

She adds that her interpretation influenced the show’s curation. “These two struck me as gargoyle-like, so I put them facing each other across the entrance like guardian figures.”

Mountains of the Mind is an aesthetic experience unlike any other at an art museum. By exhibiting a centuries-old tradition alongside modern-day interpretations, curator Rhiannon Paget is contextualizing the magnificence of nature’s hand within the aesthetic framework of abstract theory.

The exhibition lets viewers traverse the landscapes of a boundless imagination and take part in appreciating scholars’ rocks as sculptural works of art.