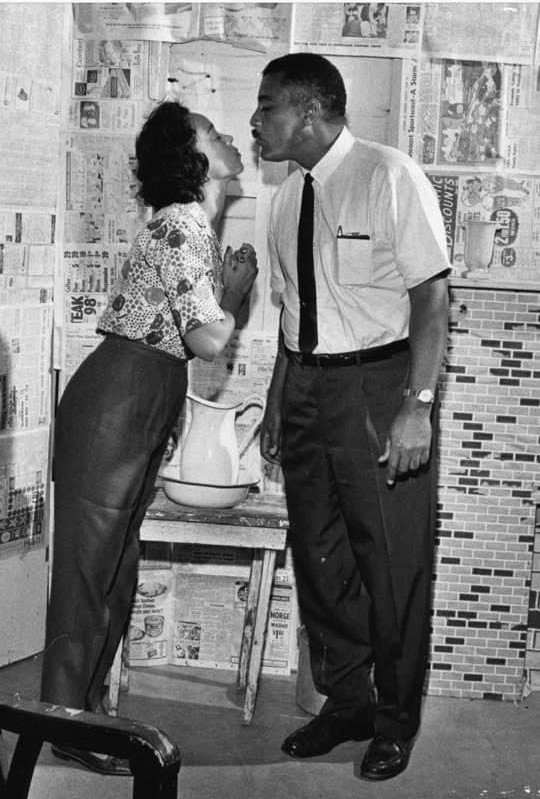

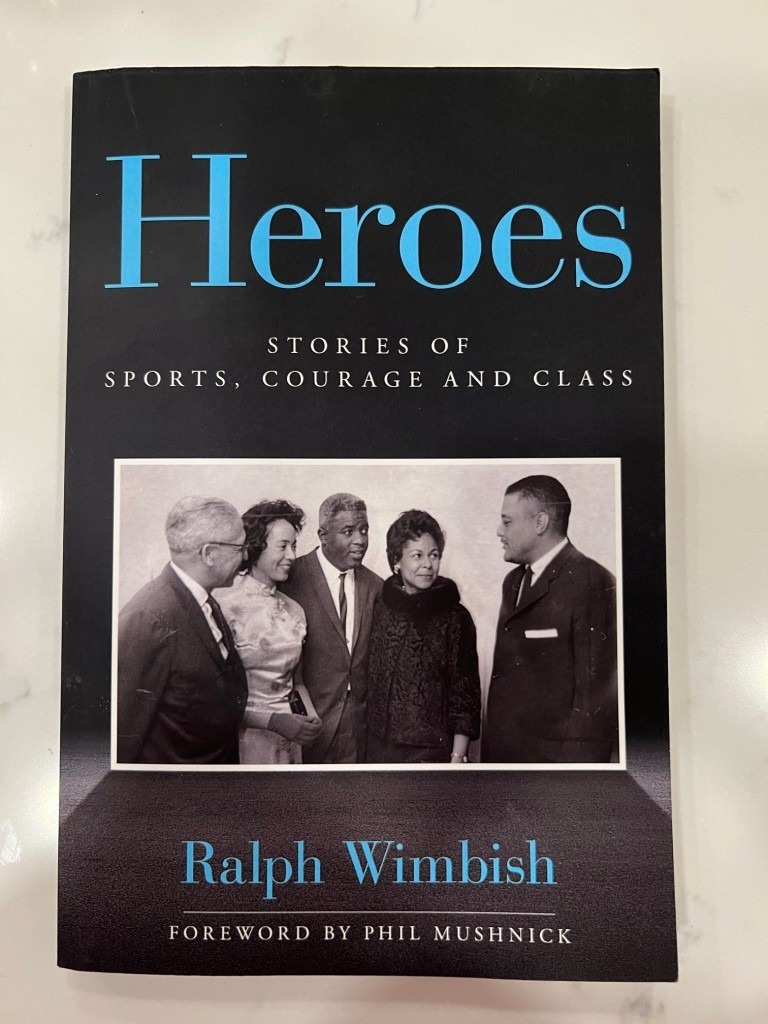

Dr Ralph Wimbish and Jackie Robinson at the

1967 St Petersburg NAACP Freedom Dinner

– photo Tampa Bay Times

. . .

By Ralph Wimbish

. . .

a selection from

Heroes: Stories of Sports,

Courage and Class

. . .

The events of 1967 continue to swirl about in my mind as if they occurred yesterday. It was an unforgettable year, amazing and historic because of what my dad, Dr. Ralph M. Wimbish, had accomplished.

Unforgettable for me because… well, because I am his son.

Anyone familiar with the history of St. Petersburg, Florida, should know how important my parents, Ralph and Bette Wimbish, were in the local fight against segregation. Restaurants, theaters, public restrooms, beaches, swimming pools, schools and hospitals were integrated by 1967, the year my dad died of a heart attack at the age of 45.

To this date, I am convinced he would have lived longer if he hadn’t spent his life fighting racism.

My dad was born in Cordele, Georgia in 1922, and he and my grandparents moved to St. Pete in the late ’20s. They lived on 3rd Avenue South in the Gas Plant district, a black neighborhood that was torn down in the ’80s to make way for Tropicana Field.

My grandmother, Inez, got a job as an elevator operator at the Princess Martha Hotel. My grandfather, Luther Wimbish, divorced her in the early 1930s and moved to Valdosta, Georgia. He remarried and in my dad’s college application, his occupation was listed as a barber.

My dad graduated from Gibbs High School and eventually Florida A&M. On his college application, he wrote that his career ambition was to be a tailor. In Tallahassee, he met a pretty coed from Tampa named Bette Davis and they were formally married on Valentine’s Day 1945, though they had secretly eloped in November 1944 in Wilmington, Delaware. He was on leave in the Army and my mom was working as a riveter at a nearby ship-building yard.

Sometime after my dad had graduated at the top of his class at Meharry Medical School in Nashville and completed an internship at Harlem Hospital in New York, my parents began building a house in Tampa on the “white side” of 22nd Street, across from the College Hill housing project.

Mysteriously, the house burned down in 1948 on the night before my family was to move in. My dad later told me he put the blame of the owner of a nearby store whom he suspected belonged to the Ku Klux Klan.

I am sure this was the fire that burned deep inside my father as he began his crusade for civil rights.

Shortly after I was born in 1952, my dad decided to move his medical practice to his hometown, St. Petersburg. Our family built another house on the north side of 15th Avenue South at 32nd Street. Because of rigid, but unofficial, zoning restrictions — the so-called red line— that barred black people from living in 100 yards of 15th Avenue, we had a big front yard.

Black entertainers and athletes who came to town in the 1950s could not stay in the city’s segregated hotels, so my dad helped them find accommodation elsewhere. Often, our house guests included Cab Calloway, Elston Howard [baseball All-Star], Dizzy Gillespie, Althea Gibson [international tennis champion], and Jesse Owens [Olympic track and field star].

You can explore the Wimbish family’s

vital role in St. Pete history on the

African-American Heritage Trail

in the historic Deuces neighborhood

and online

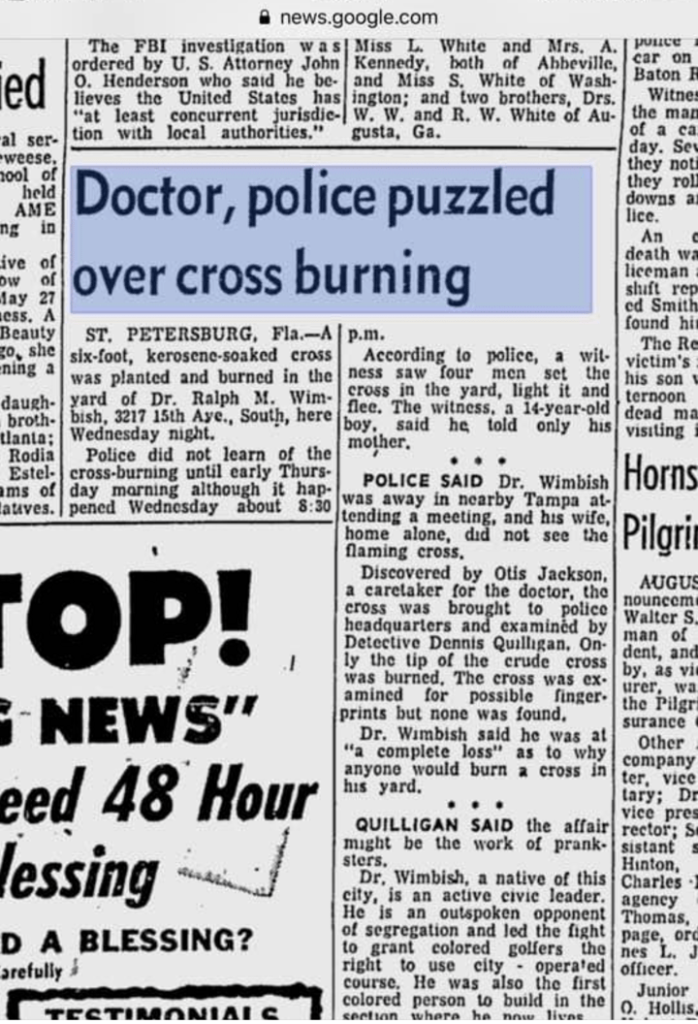

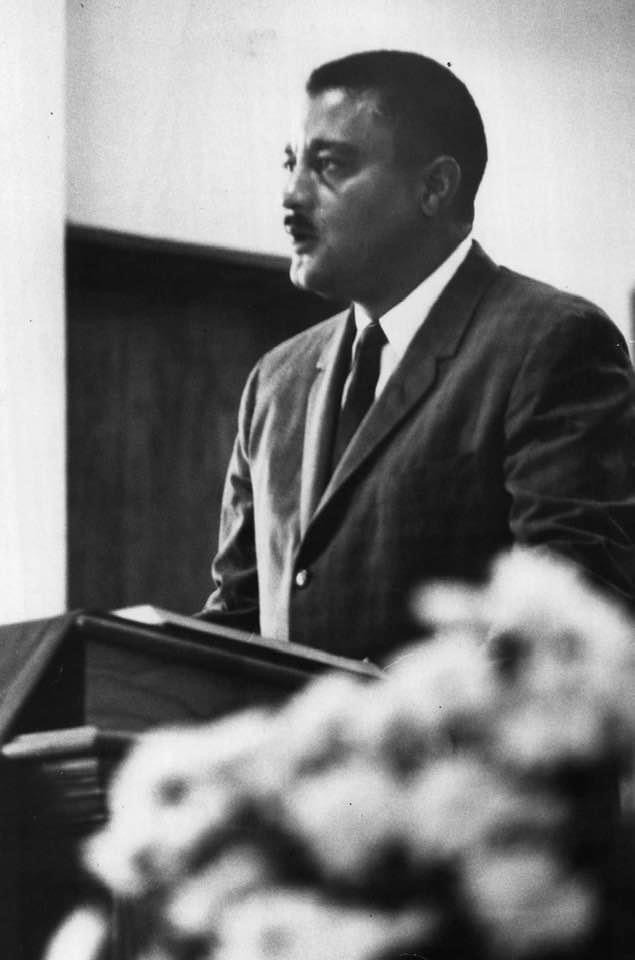

All this time, my dad campaigned vigorously against racial injustice. An imposing 6-foot pillar of testosterone with a mustache, he was a larger-than-life advocate of equal opportunities in health, housing and education. He became the local NAACP president in 1959 and organized a successful nine-month boycott of Webb’s City, the giant downtown department store.

In 1961, he drew national media attention for teaming up with Bill White, Bob Gibson, Curt Flood, and other Major League Baseball stars to end segregation that prevented black players from staying in white hotels during spring training.

My dad also founded the Ambassadors Club, an organization of black professional men that became influential in many community-service projects before it disbanded in 2005.

In addition, my dad filed lawsuit after lawsuit and attended countless county school board meetings, arguing vocally that black schools and black students were being shortchanged.

My mother, meanwhile, was no ordinary homemaker. While pregnant with my brother, she courageously ran unsuccessfully for the school board in 1960. She also fed our family, drove us to and from school and attended various community meetings. She also attended most my baseball games when I integrated the Lake Maggiore Little League in 1964.

My mom entered college when she was 16 and had her heart set on becoming a doctor. While my dad was at med school, she took a job as a junior high school teacher. In the early ‘60s, she wanted to attend Stetson Law School, not far from our home. But Stetson did not admit its first black student until 1971.

Eventually, she was accepted at FAMU law school, and my parents made the tough decision to split up our family. With my sister, Barbara, already at Howard University, my baby brother Terry and I went to Tallahassee with my mom in 1965 while my dad stayed home to support us.

Personally, I hated Tallahassee. I hated to leave spring training, my friends and schoolmates back in St. Pete. Most of all, I missed my dad.

Usually, once a month and most holidays, we would make the 250-mile drive home, or my dad would come to Tallahassee. Still, we longed for the day until we again would be a normal family under one roof.

Because of that, my mom was determined to zip through law school in just 2 1/2 years, all the while attending to the maternal needs of my brother and me. When the summer of 1967 arrived, she had just one semester to go to get her degree.

That summer of love was just that. It began with my sister’s graduation from Howard and ended with her festive wedding reception in early September. In between, I worked for Charlotte McCoy at Doctors Pharmacy on 22nd Street. It wasn’t my first job — I sold Cokes at Florida State football games the previous fall — but now I was earning $1.25 an hour as a stock clerk.

I played baseball that summer at Hoyt Field in Gulfport, and I smoked my first (and last) cigarette. Unlike years past, I could go to Biff Burger or Wolfie’s restaurant in Central Plaza without having to use the back door.

When I got my learner’s permit, my dad took me to a nearby parking lot to give me driving lessons. And there was golf. My passion for the game today wouldn’t exist if my dad had not taught me to play at Airco, a local golf course he personally integrated. To some, he was St. Pete’s version of Martin Luther King Jr. To me, he was my Earl Woods.

When summer ended, I talked my parents into letting me stay home to start my sophomore year of high school at Bishop Barry while my mom and brother returned to Tallahassee for the final three months.

That fall, my dad and I became closer than ever before. We played some golf and got to watch the final weekend of baseball’s last truly great pennant race, when Elston Howard and the Red Sox sneaked into the World Series. My dad loved baseball. In 1960 and 1961, he took me to New York for the World Series. We got our tickets courtesy of Elston.

My dad was still a busy man, and I really began to appreciate the time he would spend with me, all the while his civil-rights activism and all those late-night house calls began to wear him down. Smoking two packs a day didn’t help either.

On the evening of December 1, my brother and mom flew to Miami to join us so we could attend FAMU’s Orange Blossom football game the following night. I should have realized something was wrong that morning when my dad told me his tongue was bleeding.

Later that night, at the Four Ambassadors Hotel, I went to sleep about midnight, only to be awaken by the screams of my mother. Paralyzed by fear, I couldn’t get out of bed. I heard the paramedics come and go before I mustered the courage to seek out my mother.

With no one to comfort her, she came running toward me. “I’m sorry, I’m sorry,” she cried out, as if she needed to apologize. “I tried to save him. He had a heart attack. I’m sorry.”

I never had seen my mother cry and, suddenly, I was in tears, too. My best friend, my dad, was in an ambulance speeding to a hospital, where he was pronounced dead on arrival.

Had he lived two more weeks, our family would have been at home, reunited again.

I stayed awake the rest of the night thinking about a future without my dad. Early that morning, we boarded a plane home and prepared for the funeral. It still amazes me that my mother kept her composure throughout those awful days. Immediately after we buried my dad, she drove to Tallahassee and took her final law exams. Thankfully, she overcame her grief and passed them all and came home with a law degree.

In 1968, she passed the Florida Bar exam and established a law practice in my dad’s medical office. A year later, she became the first African American elected to the St. Petersburg City Council, beginning a long, distinguished career in local and state government.

“I did what I had to do,’’ was all my mother would ever say.

Yes, she did. So did my dad.

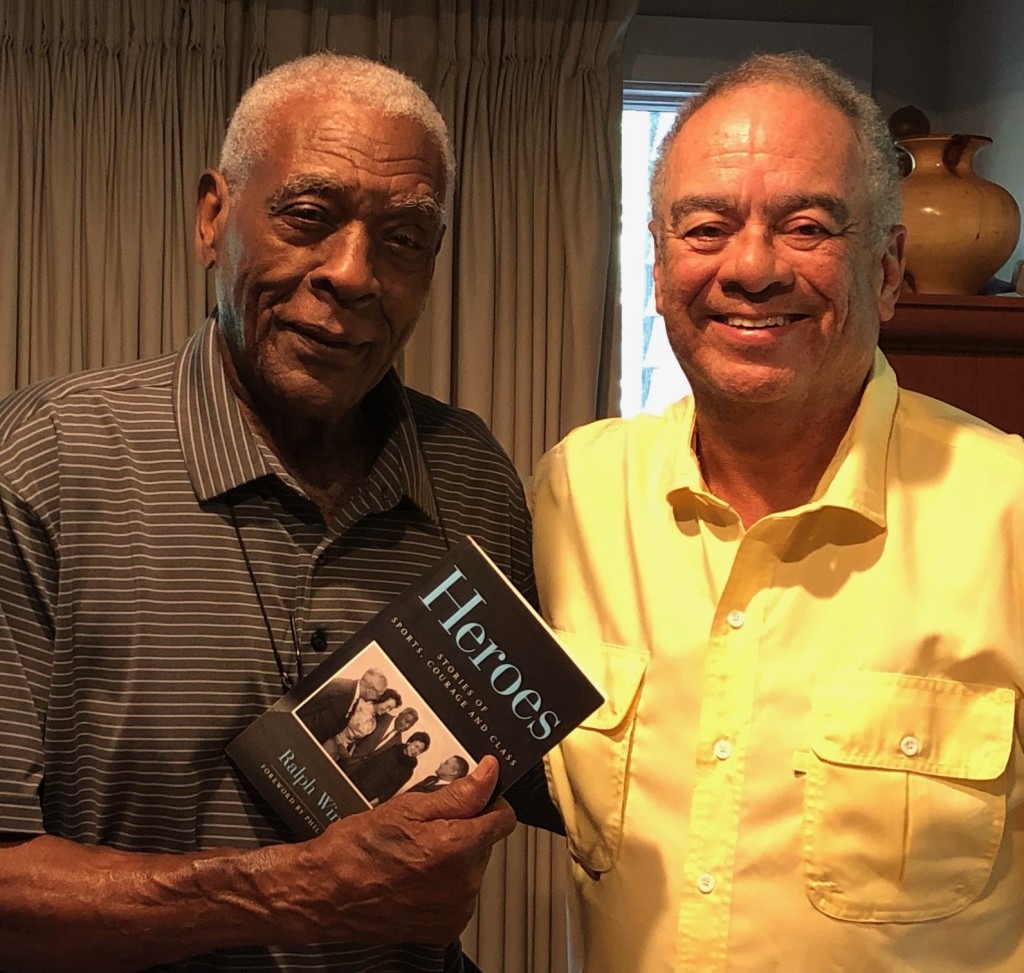

This is a chapter from Ralph Wimbish’s book

“Heroes: Stories of Sports, Courage and Class.”

You can find the complete book here.