Tom Jones: Here We Stand

Through August 27

Museum of Fine Arts, St. Pete

Details here

Here We Stand is a mid-career retrospective of photographs and collages by Ho-Chunk artist, Tom Jones. Jones interprets the contemporary Native American identity with poignant humor and irony by photographing his tribe and how it’s represented.

The exhibition is a mixture of several series including mixed-media portraits of tribal citizens, conceptual still lifes of cowboys-and-Indians playsets, snapshots of tobacco offerings and doctored artifacts.

The show includes several series that resemble conceptual practices of photography like those from the Pictures Generation of the 1970s, the ‘banal’ and ‘deadpan’ theoretical practices of the 1990s, and the depictive experiments of the Helsinki School in the 2000s. We see pluralistic images that represent multiple perspectives and eras in one photograph alongside vernacular photographs that look like someone in your family is documenting your life for you.

The first room of the exhibition consists of black-and-white reportage-style photographs of Ho-chunk citizens in their homes, at pow-wows, and living their lives in ways that celebrate their culture. The photographs were created while Jones was in graduate school at Columbia College in Chicago, and are the earliest examples of his work in Here We Stand.

Dorothy Crowfeather (1999) is a snapshot of a young girl cheesing for the camera. She’s head-to-toe in Ho-Chunk regalia with her neck and waist wrapped tightly with beads strung in triangular patterns. She stands in an open field that looks like it holds soccer games when it’s not hosting a pow-wow. We see a crowd of people behind her sitting in folding chairs and seeking refuge from the Sun under pop-up tents. In her hands is a Super Soaker 100 – the weapon of choice for children growing up during the 1990s.

Bill O’Brian (2000) shows an elderly man relaxing in a comfy chair, in a living room, with a dreamcatcher hanging above his head. A painted portrait of a younger man wearing feathers and beads and brandishing a rifle hangs on the wall to his left. Other than the moccasins on his feet, the elderly man’s attire is quintessentially American – blue jeans and a button-up.

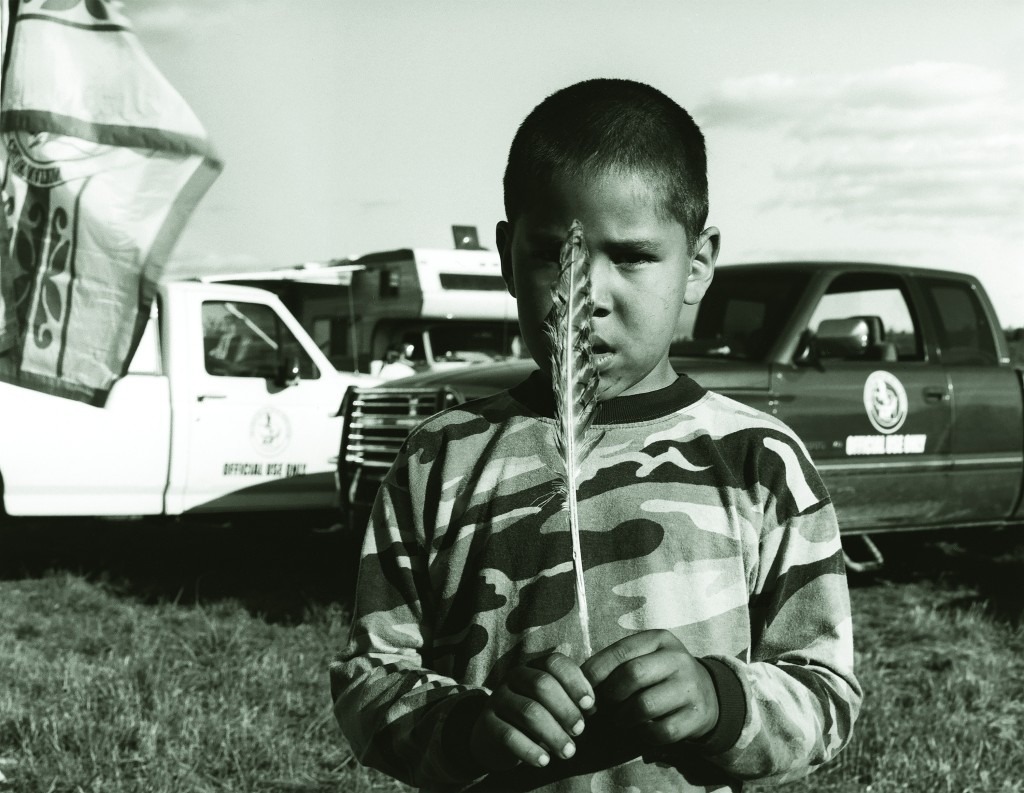

James Hill (2001) is a close-up of a child holding a feather in front of his face. The child is so young that the quill of the feather sits at his torso and its vanes extend all the way to his forehead.

In the upper-left of the frame is a waving flag with an insignia that’s also emblazoned on the doors of pick-up trucks parked in the field behind him. Printed on his shirt is that Pop-military camouflage pattern that movies and music videos made popular at the time. The expression on his face is not one of a child. He looks serious, reverential toward the delicate feather he holds in his hands.

The main gallery transitions to Jones’s more conceptual photographic practices. There are colorful still lifes, Richard-Avedon-esque portraits taken on that quintessentially white background, collages with diamond-like beads and sequins bedazzling appropriated images of racist, anti-Native images of the past – and in the middle of the gallery, a small room with close-ups of cigarette packages and lighters neatly placed in front of pictures of people in uniform.

I am an Indian First and an Artist Second is a depictively abstract series consisting of large, mostly black images of chromatic blobs hovering like a Ron Gorchov painting.

For this series, Jones used a flatbed scanner to capture the bottom side of miniature figurines from children’s cowboys-and-Indians playsets. As we all remember, the miniature legs of the small figurines in those playsets were adhered to a flat, globular-shaped foundation so they could stand upright while enacting imaginary battles. But the battles play out somewhere off-camera in this series because all we see are the zoomed-in, abstract shapes and the vibrantly saturated, childlike color palette created by viewing the figurines from underneath.

In this series, Jones is giving us a new perspective on things we all probably assumed couldn’t yield anything we didn’t already know. In doing so, I am an Indian First and an Artist Second may be interpreted as an allegory for how American society should view Native American cultures from a new, more nuanced perspective.

One series in the exhibition that provides such nuance is Identity Genocide. The modern Native American identity is characterized by cooperation and dual-citizenship. Tribes independently determine who’s a citizen — usually by bloodline — but those same individuals are usually also citizens of the State in which they reside, and because of that, can vote in local elections as well as enlist in the armed services.

For the last few generations, there have been many tribal citizens who’ve lost their lives fighting to protect the American way of life.

Anna Rae Funmaker (2015) depicts an offering to the deceased. It shows a framed, black-and-white military portrait of a young woman whose cap has a United States Air Force insignia on it. Beside her portrait is a framed, yearbook-style photographic print of her entire squadron that reads ‘LACKLAND AIR FORCE BASE’ and is dated 1936.

Sitting in front of the frames is a small wooden bowl with two packs of Marlboro cigarettes and a lighter in it. The objects are placed snugly on a small table a few feet above the ground in front of a galvanized steel pole that extends upward out-of-frame.

The side gallery is a more intimate, quieter setting, and the work on display includes some of the exhibition’s most ironic and sardonic imagery. The large, color photographs include commercialized representations of Native American culture photographed in a deadpan way that emphasizes their bastardization.

The photographs’ seemingly disparate and anachronistic juxtapositions create wry visual puns that leave an aftertaste of self-deprecation.

Like the photography of Martin Parr, Jones’s series “Native” Commodity re-presents the world around him with witty irony. Black Hawk Motel (2006) shows an aged, retro-futuristic-looking roadside sign advertising the liquidation of items like ‘SMALL FRIDGES,’ ‘MATTRESSES’ and ‘TVS’. Off-camera, we’re led to believe that the aging motel is going out of business.

The declining American economy is depicted in the image, and the pride of the booming yesteryears seem like little more than fading memories. As such, the photograph serves as an allegory for the motel’s namesake – Black Hawk, the Sauk war leader who rallied the Ho-Chunk, Potawatomi, Kickapoo and Ottawa alongside the British against the United States army in the War of 1812, but whose legacy has since been co-opted by Chicago’s professional hockey team.

The North American Landscape is a series of still lifes of various types of trees and foliage from children’s toy playsets. Each photograph in the series consists of one type of tree from the playset with a title that names the tribe who lived where that tree can be found.

Taken on a stark, black background accentuating the vibrant greens and browns of the molded plastic miniatures, this series recalls the history of nature mortes — French for ‘dead nature’ — a genre that utilizes representations of bounty and abundance to signify ephemerality and mortality. Instead of photographing hunted pheasants, wilting flowers, or skulls, so indicative of the genre, Jones represents life and death by depicting objects that were never alive.

The title of the series references a photography series of the same title by Edward S. Curtis, who, in the 19th century took an exploitative approach to photographing tribal communities by making them seem primitive, vincible and racially distinct from those who sought to colonize westward.

Jones’s appropriation of Curtis’s title mimics how Native American culture has been co-opted by American culture. By re-co-opting and re-appropriating the landscape where those tribes once lived — even if all that’s left are fake, plastic trees — this series symbolically reinstates what once was.

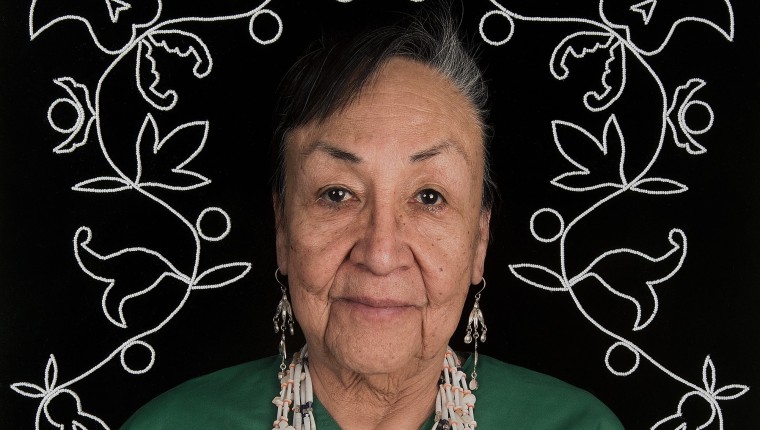

JoAnn Jones (2015) is a portrait of the artist’s mother. Behind her is a stark, black background. She addresses the camera directly with two highlights from the photographer’s studio lighting reflected in her dark-brown eyes.

Around her neck hang long necklaces of white beads made from quartz and glass. Her dangling earrings glisten with silver, and so does the large broach that hangs from the collar of her forest-green blouse. The silver broach is in the shape of a bear’s paw to signify her clan.

In the image, above Jones’s mother’s shoulders and around her head, are shiny beads adhered to the surface of the photographic print. Decorative circles and flowers hover over the black background surrounding her, creating contour lines in symmetrical patterns and shapes.

During a recent talk at the MFA, she retold the story that inspired the series. . .

“I’m also looking for spiritual awareness, and why we are living. Why are we here? That’s a question that’s always been in my mind. So, wherever I go, I’m in contact with people who are spiritually searching for the meaning of life as well.

“For example, I always wanted to talk to a medicine man, and to see one of their ceremonies. So, we went to South Dakota, when the kids were young, and went to a medicine man’s ceremony. During the ceremony, these women started to sing in Sioux. They were singing, ‘Spirits and ghosts, come on in! Spirits and ghosts come on in!’

“And they did.

“There was a lot of sound – like someone hitting the walls. Then, this man who had brought me said, ‘They’re coming.’ When they started coming in, you could see the lights like little white flickers, like fireflies. Then the guy said, ‘They’re coming around to heal you. And when they do, don’t reach out. Don’t try to touch them.’

“And so I didn’t.

“They started coming toward me and working on me. I closed my eyes thinking, ‘Maybe it’s just my imagination.’ So, I opened my eyes again, and I closed them real tight, and I opened them again, but they were still there. Just floating around.

“Tom was with me, and he saw it too. At the time, I didn’t realize it’d made such an impression on him. He said, ‘I saw them too.’

“When you see the photographs, he added the beads and shiny crystals to them. He said, ‘That’s my interpretation of our people being surrounded by spirits.'”

When she was just a child, about third grade, Jones’s mother, along with the rest of the Ho-Chunk children, were forcibly removed from their homes by the United States government and sent to a boarding school. For Dear America: Our Father’s God to Thee (2002), Jones appropriates a group portrait from his mother’s boarding school that shows three rows of children in front of a building that looks like a prison.

At the bottom of the image is text that appears contact-printed into the photographic paper and reads, ‘Bethany Indian Mission Wittenberg Wis.’ In the area above the children, on the balcony, stand the school’s headmasters. Jones adds text above their heads that reads, ‘OUR FATHER’S GOD TO THEE.’ In the margin of the image is a hand-written account of what his mother endured.

Here We Stand offers a perspective of the Ho-Chunk, and the Native American identity as a whole – that’s altogether new.

Jones’s photography and collages show us insights and opinions in styles that are emblematic of contemporary artistic theories and practices. His work has the power to portray that which remains hidden despite being so blatantly obvious, and his wry delivery oftentimes yields a chuckling acknowledgement of his wit.

The more documentary, reportage images offer glimpses into the Ho-chunk experience. The more abstract, conceptual practices allow us to empathize with a nuanced critique.

The exhibition paints a picture of Native American culture that’s long overdue for an update.