. . .

Twenty years ago in Barrie, Ontario, Janet Lee – now a Safety Harbor resident – was doing her best to engage a classroom of tired teens. Students, for whatever circumstances, who were considered difficult to teach.

Little did she know that the next few hours would mark the beginning of a beautiful friendship, life lessons – and that in 2023 she would collaborate with an Emmy award-winning director to create a documentary – Always Ask For Help – inspired by events that started on that day.

“I was having a hard time connecting with them,” she says. “Maybe it was because it was first thing in the morning. Teenagers are sleepy that early in the morning.”

As if the day couldn’t have started worse, Lee was interrupted by the intercom, asking her to bring her students to the library to hear a guest speaker. “The students were mad that they had to walk down three flights of stairs,” she says.

She hadn’t expected a speaker that morning, especially not the older man who sat at the front of the library. He was disheveled, noticeably shaking. A pack of cigarettes peeked out of his shirt pocket. She took a deep breath and approached him. “I asked if he needed water. He was so nervous.”

Lee and her students sat and listened to the man’s presentation. “He said, my name is Arnie Stewart. I was in grade one for two years, grade two for two years, grade three for two years, grade four for two years, and grade five for one hour. I got kicked out of school when I was 15, and I could not read or write.”

Arnie was eating from dumpsters and living in a parked car, turned down from many jobs, and struggled his whole life bluffing his way through low reading and writing skills. Arnie blamed himself because he never asked for help.

“By the time he finished his story we were all crying.”

Janet Lee and her students silently climbed the three flights of stairs back to the classroom. “One of my students was very emotional. He put his hood up. Everybody was around him. I said, Chris what’s happening?

“He said, I’m Arnie. I need help.

“I had this beautiful classroom. We called it 302, the room-with-a-view. I had a view of the lake, and the parking lot was there. We looked out the window and he said, see that car in the back of the parking lot? There are people in it. We live in that car. That’s my family. I’m Arnie. I need help.”

As soon as the bell rang, Lee walked Chris to the counselor’s office then rushed to the main office. “I asked, where’s Arnie? Did he leave?”

She remembers her relief when she saw him across the room, sitting in a chair and looking at a map. “He was trying to figure out how to get to his next school. I sat next to him and said, you don’t know me but I’m Janet Lee and I want to write your book. I’ve never seen anybody make an impact like you. My students are different now.”

During planning period, Lee drove in front of Arnie to the next school where he was to speak. She finished her day, reeling with the emotions this humble stranger had bestowed. Those feelings stayed with her on the drive home and as soon as she entered her house, she told her husband her whole life had changed.

“He said you can’t just tell some stranger you’re going to write his book,” she says. “I was discouraged. I put it down for at least a year. I tried to forget about it.”

Inspiration and Renewed Purpose

After a workshop with Natalie Goldberg, author of Writing Down the Bones, Lee had a revelation. “I needed to connect with Arnie and help him tell his story.

“Our first meeting was at the McDonald’s. Arnie, his wife Barbara, and me.” Lee gave him a gift—a journal. “It was very insensitive. Because little did I know, he was telling everybody he had learned to read and write. This man wasn’t writing at all. When he died, I got the journal back, empty.”

Not only had Arnie made Lee believe he had learned to read, all of the children he spoke to believed it as well. The literacy center that sent him to the schools to speak, must have assumed it too.

Much of his life was spent figuring out how to get by while not giving away what obviously felt like a shameful secret.

“What I didn’t know,” Lee says, “is the literacy center that organized this trip for him didn’t ever organize a place for him to stay. They said here’s the address. You have a speech at 8 a.m. This school was at least an hour from his house, maybe two hours, so Arnie drove there the night before to avoid getting lost and being late for his presentations.”

She learned that after he was kicked out of school at age 15, Arnie hitchhiked to Niagara Falls. He slept in an abandoned car and ate food from garbage cans.

She learned ways in which someone with low literacy gets by in society. When Arnie wanted to eat at a restaurant, he’d look around to see what people were eating and order the same. He couldn’t fill out applications for jobs. Later, when he worked as security at the border, he walked around with a newspaper under one arm, pretending he could read it.

Serendipity was at play when Lee received a promotion. She took on the role of literacy consultant with the responsibility of training teachers at 126 schools. “That’s a lot of teachers. I thought, I’ll get Arnie to go to the schools and speak. The teachers would encourage the students to generate questions for Arnie before our visit.”

He Became a Living Text

“In Ontario there are four strands of literacy – reading, writing, oral language and media literacy,” Lee explains.

“The oral language piece is really hard to get at and that’s what Arnie was, an oral text and a real live person. You make inferences based on what he was wearing, how he acted, what tone of voice he had, and how he told his story. Every single audience we went to— fourth graders, were absolutely quiet during the talks. We never had a problem with any student misbehaving, ever.

“Then when we left, they would write us letters and that was the writing activity that went along with the lesson plan. Every time he would talk in a school, they would write him letters and he’d have to read them all and slowly, he got better.”

She remembers how proud Arnie was to get all of those letters—about 5,000 in total. The pressure to fulfill the initial promise she made to him began to overwhelm her. “I only write teacher guides – my thing is not writing a book,” she says. “It was this insurmountable thing.”

Traveling to Where it All Started

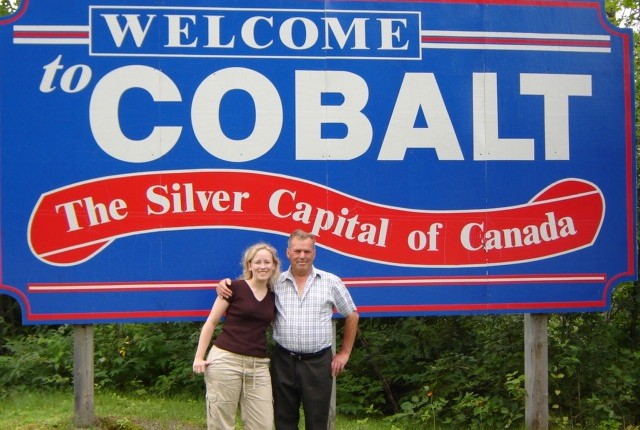

In order to tell his story, Lee needed to see the place Arnie came from. She wanted to understand how the education system had failed him — how society failed him. She wanted to meet his family. “So I had a semester off,” she says. “We went to Cobalt.”

Arnie and his 12 brothers and sisters, his mom and dad, had lived in a small home that Lee describes as a box. There was one bed for the boys, one for the girls. The holes in the roof made the sky visible through the ceiling.

“This is Canada, northern Ontario,” she stresses. “It is so cold that when you light a fire and the smoke comes out of the chimney, it slides down the side of the building. Snow is there until May.”

She met everyone and remembers that they all had varying degrees of broken hearts. None of them had ever had it easy.

Arnie was given the Queen’s Jubilee Award before Lee had met him. It was something he was very proud to have. Lee created an award inspired by it to give to students. “It wasn’t for the kid who had straight A’s – it was for the kid who was determined, maybe they struggled with literacy but they had the help of their family and overcame it. Arnie never got an award as a kid.”

The first recipient of the Stewart Family Literacy Award was an 11-year-old named Mitchell Bannister.

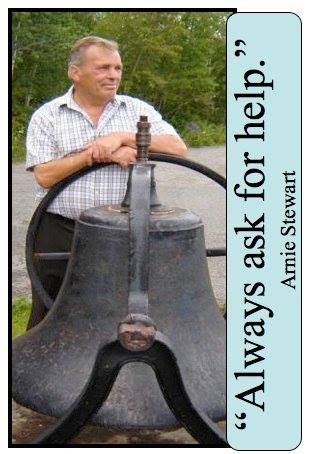

Knowing they needed a way to help the kids remember Arnie’s message, Lee created Arnie Cards after visiting Cobalt and seeing what remained of the old schoolyard.

“We found his school bell in the yard in front of his old school. He plopped his arms down on the wheel. It became an iconic photo, the one we used on the cards.”

On the back of the Arnie Card, a kid would write their name and then hand it to a teacher. Not a word had to be spoken — just the action of handing someone a card was like a secret sign to let that person know they needed help.

After one of Arnie’s talks, a teacher approached Lee. “He said, so Arnie was 15 when he was kicked out of school, right? What was the name of the principal?”

Lee answered and the teacher told her he knew the man. The old principal was still alive and he lived there, in the same town where Arnie had just shared his story.

“We were 430 kilometers from where Arnie grew up. The teacher asked if Arnie would like to meet with him.” Lee pauses. “This man told Arnie he would never amount to anything.”

But Arnie Wanted to Meet with Him

Janet Lee and Arnie went to the school’s library and waited. “In comes the old principal with a walker,” she says. “I gave him an Arnie card. He sat there, staring at the card. He said, I remember you Stewarts. You carved your name in a desk.”

Arnie was sitting directly across from the man who had given up on him. The principal who could only see Arnie as that boy 50 years ago with his 12 brothers and sisters. “He said to Arnie, you were bad kids. Arnie was like, yeah, we struggled. We had hard times. We were poor.”

In the quiet that followed, Lee heard something hitting the table. “They were Arnie’s tears,” she says. “Arnie said, you know you told me I’d never amount to anything. But talking to these kids, I think I finally made it.

“The principal was sitting with his arms crossed. He said, Arnie, it seems to me you have.”

Returning to the USA

Lee and her husband decided to move to Florida. “At that point, Arnie and I had spoken at 72 schools, often three schools a day. But the board office told me they had a new dean for me and she brought me in the office and said I know Arnie’s your baby but you can’t do this anymore.”

During their time together, Lee had given him every dollar the schools paid for his talks. It was their work, their partnership. It was Arnie’s life. “I had to hook him up,” she says. “I had to find someone else.”

Lee and her husband moved to Safety Harbor in 2012. “We were here in March and in August, I got a call from Barb and she said they’ve diagnosed Arnie with lung cancer.”

They Gave Him 11 Days to Live

“I landed in Toronto and drove to Niagara Falls where he was. I went to the hospital which was an old elementary school, super dirty. The last thing he ever said was, Tell the kids to never be afraid and to always ask for help.”

When Arnie died, his son called Janet Lee. “Before the coroner arrived. His son said we just want to thank you for all you did for my dad. They put me in the obituary. They said I was part of the family.”

There was no funeral.

Fulfilling a Promise

“I wrote it in different ways. A three-part book – Arnie, me, and Sheldon, a kid we always used to go see. The book still felt overwhelming.”

Lee attended meetings to learn to write a screenplay. She was invited to a screenwriters group in St. Pete. There were a lot of filmmakers there. One was Joe Davison, who approached and asked about her story.

“Arnie Stewart,” she pitched. “He grew up with low literacy. Never learned to read and write. He went to the no frills grocery store. He looked for something to make the kids for dinner. He saw a can with the word beef. His kids all had dinner — stew. The next day his wife came home, she looked in the garbage. He had fed his kids two cans of dog food. “

With Davison’s help, the script was finished in two weeks. “Joe is a horror movie guy,” she says. “He went on to the Stranger Things Netflix series. He is really successful now.”

She and Davison sent the script to Hollywood. Hollywood sent it back for edits. Lee was certain it was going to happen.

So many people believed in her project and she knew she was on the right track. But soon enough, she was back at the beginning.

“I ended up getting divorced. I decided I was changing my life. I went back to school and got my master’s, but it’s always been about literacy.

“This instructional design degree I have really helps me get things out in the world in a huge way. I got to be part of a MOOC, which is a massive open online course. This course was for instructional designers to learn how to make materials for people like Arnie. I got to add Arnie’s story as one of their personas.

“The Hollywood thing. . . it went away. I never heard back. I ended up hiring somebody else to write the screenplay again. I kept doing things and every time I’d talk about Arnie, somehow.

“Last year I was working with a teacher from Southern New Hampshire University through the instructional design company that I work for. I got to pair up with a faculty member who asked me about my story.

“He has a friend named Rebecca Hogue and she’s Canadian and has a great podcast about instructional design and demystifying the whole career. Before I knew it, I was on Rebecca’s show.”

The episode was called Always Ask for Help and it became widely circulated. Soon, Lee was contacted by Louis Chesney. They spent a while talking about his own experiences and struggles. “He’s the nicest guy,” she says. “Finally, I asked, why are you really contacting me, Louis?”

That call became the pivotal moment that she’d been working toward for 20 years. Louis introduced her to Scott duPount, and he loved the story — enough to help her make it happen.

He suggested they make a documentary and then introduced Sylvia Caminer. “She did Follow Her and Places to Love, a travel series,” Lee says. “That’s what she won her Emmys for.

“Next, duPount got an entertainment lawyer on board. They wrote a business plan.”

The film will be in three acts – Arnie’s story, Arnie’s story with Janet Lee, and what his legacy means today. “I said to Sylvia, we have to go back to Canada before it snows. If we don’t do it now, we will have to wait another year.”

Returning to Cobalt

Back in Cobalt, the film crew, Lee and Caminer met with Arnie’s living siblings — all in their 70s and 80s. Lee told them the story of meeting their principal and what he’d said to Arnie. “He was saying all the Stewarts made it.

“It was like they transformed in front of my eyes,” she says. “They stopped talking about it. I was again a teacher, standing there, telling them their principal had a moment of reckoning. I saw it mattered.”

Lee stepped out onto that beach at Minet’s Point Park. She was there with the film crew for a photo shoot. The beach was covered in white feathers, like all the birds on the lakefront were molting.

She and Arnie used to pick up white feathers. And Mitchell was there — the first recipient of the Stewart Family Literacy Award.

“Literacy rates are low in the prison system where Mitchell works. He plans to continue telling Arnie’s story.

“The movie has turned into a ripple effect,” she continues. “If you take a moment and go back in time, sometimes you can see that yes, you did make a difference.

“Now, Mitchell will carry the torch. How one life can touch so many others. We all have that, we all touch somebody else’s life. All of us can cause a ripple effect.”

All of the film footage has been captured and after 20 years spent traveling with Arnie, seeing his impactful message change lives – and Lee herself speaking to thousands about the importance of not only asking for help, but being the one to help, production is finally underway.

“Any documentary can tell a history story but any that can inspire. . . well, this is what I’ve always wanted to make. It’s about Arnie but it’s about now, about teachers, about today,” Lee says.

“When you have a dream, you have to resolve it.”

. . .

Free Reading Resources

. . .

Literacy Council of Upper Pinellas

Pinellas Early Literacy Initiative

St Pete Library Early Literacy Summer Reading Program

Training as a Volunteer Reading Tutor

Find Places to Volunteer as a Reading Tutor

To follow the documentary’s progress and for information

about Janet Lee and her team, you can visit everythingjanetlee.com.

You can find out more about supporting Arnie Stewart’s message

and this film by emailing everythingjanetlee@gmail.com.