Challenge and Taught Us About Courage

. . .

White Rabbit, Red Rabbit by Nassim Soleimanpour is, hands down, the strangest play I’ve ever seen.

I use the term “play” loosely. As the Iranian author himself freely admits (speaking to us across the span of time and space through the “Actor” who has agreed to perform his work), White Rabbit, Red Rabbit may not be a play at all.

It might, he tells us, more accurately be called an “experience.”

Or as one critic described it, “a cross between a psychological thriller, a double-blind social experiment, and slightly disturbing performance art.”

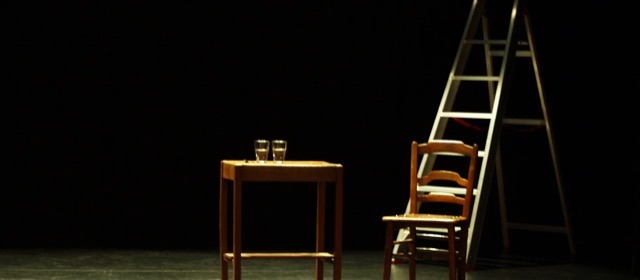

I saw this “experience” twice — first starring Fanni Green and then a couple days later with Beth Gelman, two seasoned actors based in Tampa Bay. Their performances were part of American Stage’s 10-show presentation of White Rabbit, Red Rabbit, staged from November 2 to November 19 with 12 different actors at different (and unusual) venues in St. Petersburg, including a Black church (Historic Bethel AME), an art gallery (WADA ArtsXchange), a creative arts district (The Factory), an event venue (Savant on Second) and a museum (The Woodson) – and in Tampa at a college campus (the USF Theatre Center).

Note that no two performances of White Rabbit, Red Rabbit are ever the same — for two important reasons.

The first reason is that any actor who agrees to star in White Rabbit, Red Rabbit can only perform the play once. They have to promise they have never read it.

They are instructed not to research anything about the play and are forbidden to go to any performances before they perform the play themselves. The first time they lay eyes on the script is when they step onto the stage and pull it out of a sealed envelope.

That’s right. No rehearsals. No preparation. Just a cold reading on the spot.

Why would an actor agree to these restrictions and sign up to do this odd duck (or should I say rabbit?) of a play?

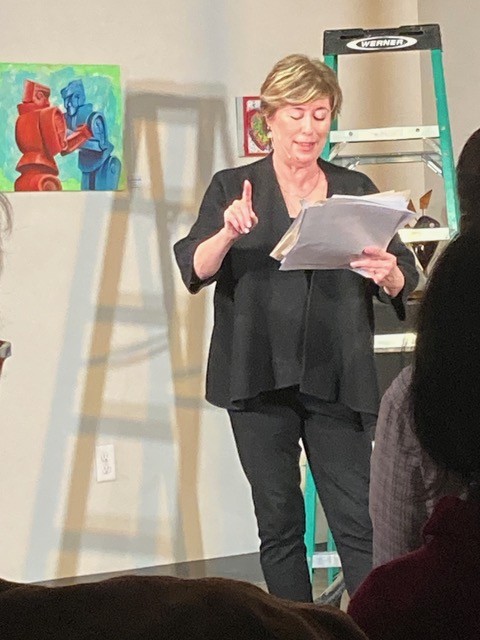

“I always like to do things that scare me,” Fanni Green told me when we sat down to chat after her energetic performance at downtown St Pete’s Historic Bethel AME Church. I posed the same question to Beth Gelman after her equally lively reading a few days later at the ArtsXchange in St Pete’s Warehouse Arts District.

“When Patrick Arthur Jackson (one of this year’s Creative Pinellas Emerging Artists) came to ask me to do this really amazing play, I told him, ‘You had me at no rehearsals,” laughed Gelman. Currently the senior director of arts and cultural programming for Creative Pinellas, Gelman knew she would have her hands full preparing for Creative Pinellas’s Arts Annual 2023 which intersected with the show’s run.

Green and Gelman join an impressive list of thespians who have agreed to perform Soleimanpour’s social experiment of a play. Nathan Lane launched White Rabbit, Red Rabbit’s Off Broadway run in 2016 which also featured performances by Whoopi Goldberg, F. Murray Abraham, Cynthia Nixon, John Hurt, Stephen Fry, Stephen Rea and Brian Dennehy. Per the rules, none of these actors will ever do the play again.

As American Stage put it in its publicity for the play – “No do-overs. No repeats. No encores. A theatrical journey into the unknown that holds endless possibilities each time you experience it.” (For a glimpse into some of those possibilities, see Playbill’s 17 Outrageous Moments from the run of White Rabbit Red Rabbit Off Broadway).

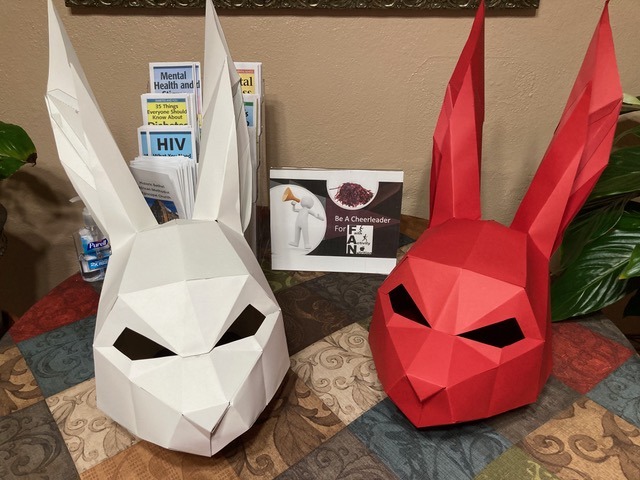

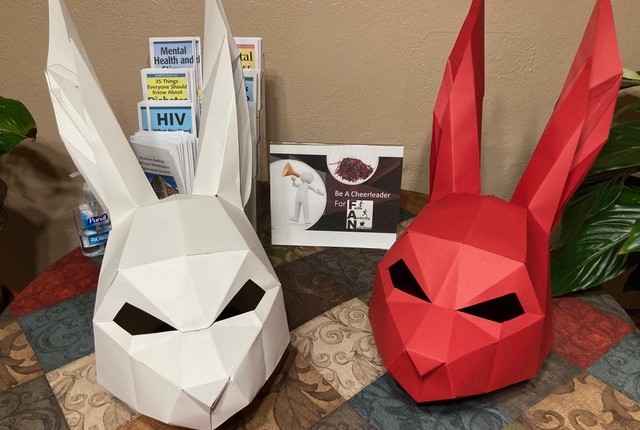

Both nights I saw White Rabbit, Red Rabbit there wasn’t really a stage, just a space carved out in the hall of a church and in a gallery space in front of rows of folding chairs. There wasn’t much in the way of a set or props either. A ladder. A table with two glasses filled with water. And a vial (which may or may not be filled with poison) which was handed to the actor when she arrived at the theater.

In the script, the actor (who can be any gender) is immediately instructed to place the vial next to the two glasses (which may or may not have poison mixed into one of them). During the course of the play when there is a need for a carrot (remember, this is a play that involves rabbits) and an entrance fee (it turns out that even rabbits need money from time to time), the actor is instructed to ask audience members to provide a dollar bill or a carrot — or at least something that could stand in for a carrot.

And that comes to the second reason why every performance of White Rabbit, Red Rabbit is unique – audience members, it turns out, are an integral part of this “experience.”

“The playwright only told one lie,” Green told me. “He said there would be ‘minimum participation’… I had no clue that the audience would be so participatory.”

Every night no one can predict how the spectators are going to react. Will they comply when they are instructed to clap? Will they rebel when they are told to close their eyes? Will anyone agree to come up onstage? “I can see how this play could get out of hand,” said Gelman.

White Rabbit, Red Rabbit premiered in 2011 in Edinburgh and at the SummerWorks Festival in Toronto – it has been performed well over 3,000 times across the globe since.

It begins with Suleimanpour introducing himself – “I was born on Azar 19th, 1360 in Tehran. That’s Tehran, December 10th, 1981 in Christian years…” He tells us he is writing the play — in English — in 2010 in Iran. He is trapped in his country, denied a passport until he does his compulsory military service.

Part of a generation that was traumatized by the Iran-Iraq War of 1980-1988, a generation of “computer-literate, well-informed young people who have never known an Iran other than the Islamic Republic,” Soleimanpour is a conscientious objector. His play, he tells us on his website, is about contemporary Iran and about his generation.

White Rabbit, Red Rabbit, however, clearly is not just about Soleimanpour’s generation, not just about Iran and not just about his failure to obey his country’s rules. It’s about all of us.

The Iranian author jars us with tales of rabbits, ostriches and poison, but as audience members are called upon to participate, it begins to dawn on all of us — actor and spectators alike — that the conformity demanded by the Ayatollahs in an Islamic state is not confined to any one country, that oppression knows no borders.

It occurs to us — and to the actors who are coming to this script cold — that the playwright is calling on all of us to contemplate our own easy acquiescence to instructions, to examine our own tendencies to easily pass down hate from generation to generation and to ask ourselves just how responsible do we really feel for others.

In their on-the-spot performances, Green and Gelman both brought the strength of their diverse backgrounds to the stage.

Fanni Green, a playwright, director and professor in the theater department at USF for more than ten years, was especially deft at “directing” the audience members when they unexpectedly were called onto the stage (urging one shy woman to “come into your light”). Providing a running commentary — at times entertaining, at times wry — throughout the play, Green always took pains to say “That was me” when she deviated from the script.

Beth Gelman, who recently appeared as activist Emma Goldman in American Stage’s production of Ragtime, channeled the nearly nine years she spent as executive director of The Florida Holocaust Museum as she read the script.

When the play turned dark, she suddenly was reminded of another time when, for lots of different and difficult reasons, people allowed terrible things to happen. “That slapped me in the face.”

Through scenes of both goofiness and horror, both actors took us — and themselves — on a roller coaster of emotions, from laughter to tears.

“I didn’t feel like an actor in the play,” said Green. “I kept feeling that it was so much in the moment. The discoveries that I made were in the moment.

“I carried the title of ‘The Actor,’ but in the end it was me, it was me making the choices.” Green said she thought that that was the intention of the playwright all along. At the end of the play, she looked truly stricken by her final choice.

“It was quite an emotional journey,” agreed Gelman, who was teary-eyed at the conclusion of her own performance. “I felt the weightiness of something terrible that could happen. The play posed a moral crisis for the audience.”

It also posed quite a challenge for the actors. “As part of the neurotic actor population, I think about choices rather obsessively,” admitted Gelman.

Actors are always overthinking their roles, tweaking them for each performance, she points out. With this play, however, there was only one chance. “When you are doing something like this, you have to just go for it, which is something tremendously freeing.”

Both actors were thrilled to perform outside the normal confines of a traditional theater.

“Look, it didn’t take much to create a stage here,” said Green, eyeing the spacious hall at Historic Bethel AME where she had just performed. “And I don’t think it’s just this play. We could definitely do Hamlet here.”

Green has had a long career in the theater, from her days acting on Broadway and Off Broadway and staging her own work at New York Theatre Workshop and the Ensemble Studio Theatre in Manhattan to her current work at USF where in addition to teaching she directs student productions. One made it to the Fringe Festival in Edinburgh and was nominated for the Amnesty International Freedom of Expression award.

Lately Green has been worrying about the state of theater – “There are so many people who just don’t come to the theater. The theater is about human experience but it almost has become an elite event.

“So to go to different parts of St. Petersburg and to be in this church, this old historic church, and bring the play to the people, that was very smart of American Stage.”

Gelman is no stranger to what she describes as “bringing art to the audience, giving them other ways of seeing it.” For years she acted in unusual venues in Chicago, one time doing a show in the basement of a bar. “It was a super weird show but people came because it was accessible or they were at the bar that night and heard they could ‘pay what you can.’”

Offering theater at an affordable price and in an unusual venue clearly works. “I thought four people would come to this play and I would know them all,” Gelman told me with a laugh. Instead she performed before a full house.

As part of her current job at Creative Pinellas, Gelman, in collaboration with American Stage, oversees play readings every month in the organization’s auditorium in Largo (formerly called First Mondays, it’s now called Fresh Ink). “We’re not going to do Mame, but the plays have been great.”

Part of her challenge with the program, she told me, has been to make the space more welcoming to people who have never been to a play. And while she applauded American Stage’s outreach throughout St. Petersburg with White Rabbit, Red Rabbit, she also would like to see more top level theatrical companies performing throughout Pinellas County.

“I feel like there is an audience that’s hungry for that even if they don’t know it yet in central and northern Pinellas and even by the beaches. There’s an opportunity there.”

In the script for White Rabbit, Red Rabbit, Nassim Soleimanpour (through The Actor, of course) repeatedly gives out his email, encouraging those who are watching the play to get in touch with him. Both Green and Gelman admit they are tempted. “I’d like to ask him where he is now and what does he think about the words he wrote as a younger man,” said Gelman.

If I emailed Soleimanpour, I would tell him that I think White Rabbit, Red Rabbit is the strangest play I’ve ever seen. And that that, from me, is high praise.