Dancer, choreographer, professor – and inventor – Merry Lynn Morris talks with Barbara St. Clair about her work exploring dance and disability, and how dance companies and educators are embracing a diversity of dancing bodies in performance.

Transcript Highlights

from Merry Lynn Morris

What I love and what excites me and has excited me for a long time now since I started the work in 2002 – I love the way that dancers with disabilities really, in my view, really push our field forward.

They make us question our training practices, how we can expand our training practices, we can make them more accessible. How we can innovate in our creativity.

Choreographically, if you have a dancer without legs or who uses a wheelchair or has another way of understanding dance or communicating through their body – that frankly, by nature, is innovative.

Traditionally there’ve been perceptions that one type of dance, particularly classical ballet, kind of sits at the top and these other things fall underneath it. And that hierarchical vision of dance is really problematic.

A lot of educators have recognized that – there’s a lot of questioning of that. It’s been going on for for some time now. Certainly it’s becoming more heightened – a discussion about race and dance, what bodies have permission to hold the spaces, how sometimes dance is racialized. In the past, it certainly has been.

But a lot of those barriers are changing. I see positive things happening. I see dancers who identify as transgendered. I see dancers of a variety of racial and demographic backgrounds. I do see more incorporation of disabilities and attention to that population, that it exists.

But I think there’s more work to do, and certainly getting the word out, making sure the visibility is there so there can be a change in perception.

. . .

We need multiple perspectives, multiple bodies. We need people from different walks of life, giving us that gift – actually giving us the gift of their experience – through dance or whatever medium they may be working through.

I’m at a university where entrance to our dance program is via audition, so students essentially come in having a lot of skills under their belt – specifically in two different forms, ballet and modern. That naturally limits someone who has a flamenco background or has a hip hop background or has not taken dance at all.

That questioning is happening a lot now with with different sexualities, different types of bodies and approaches to what dance looks like, to really reshape something that’s been embedded for a long time.

There’s a process for reconstructing curriculum, particularly in relationship to race, because that’s one of the biggest conversations going on. Educators are questioning the design.

Who are we designing things for? Who is being left out of the room and who’s being included? Is there predominantly one racial representation here? And why is that? Is there predominantly one type of sexual orientation here? Is there one type of ability?

Disability can be a very fluctuating thing over one’s lifetime. . . mentally, physically, whatever it might be. It it is an interesting space because of that kind of fluidity a disability might have – even a permanent disability may fluctuate in its nature. Maybe one day [a person is] experiencing a certain kind of thing in their body, another day it changes.

Human mobility is important to us all, whether we’re driving cars, riding bicycles, climbing ladders or whatever kind of tools we’re using to get us from one place to the next.

You and I are using [Zoom] technology in order to interact, in order to produce something that will go somewhere. It’s a mobility tool. If I take off my glasses, I can’t see the hand of hand in front of my face. It’s a mobility tool, to allow me to interact with my environment. It’s essentially an assistive device.

And so I think that access tools or mobility tools are important to all of us. Innovating inside of that space is important to all of us because it affects how we can extend our capacities, our abilities to interact with the world.

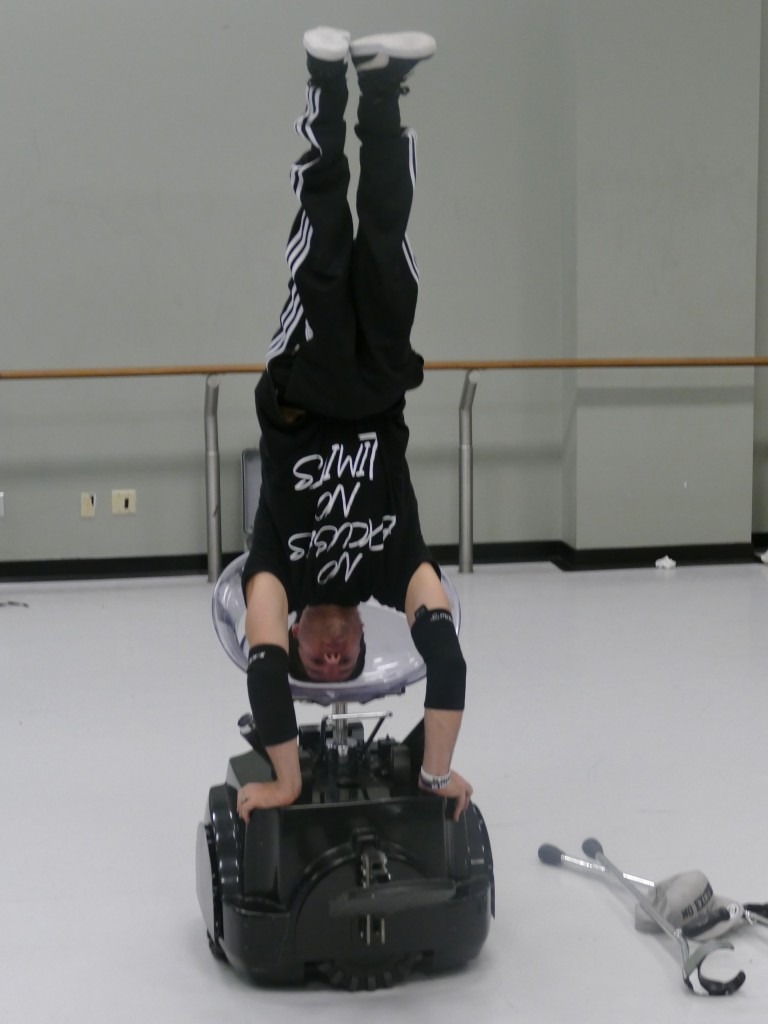

If wheelchairs or mobility devices from the outset were thought of as needing to be dance-specific, how would they have evolved? That sort of was my entry into looking at both the aesthetics of the form as well as looking at the controls.

In particular, I was interested in creating a hands-free control. How could the dancers lean forward and lean back? Lean forward and go forward. Lean back and go back and move through space?

So that led me down the path of working with engineers, collaborating with engineers at USF, doing my own research in existing technologies and seeing what was out there and putting Segway technology, gyroscope technology in response to basically weight shifts as you’re standing on the device. Well, what if we mounted a seat on a Segway? Where would that get us? Is this really a useful idea?

I think reflection and questioning is always an important part of any practice. Is this a good solution? Is this a helpful solution? Who is it helpful for? How do we make it better? Those are my questions.

And so I have I have a prototype device. The mobility devices that have been developed so far, there have been five U.S. patents received for them.

That’s what we do as creative artists is explore and invent and collaborate together.

Dance medicine, dance science has to do with the health and wellness of performing artists – whether it’s mental health, physical health. So we’re talking about our training practices, we’re looking at flooring, we’re looking at shoe wear or costuming or whatever has to do with health and wellness and how do we train dancers better and how do we train them longer and create longevity in the field mentally and physically. That really interests me a lot.

There’s another piece of dance medicine / dance science that includes dance for health – using dance in different settings with different people, for social impacts. . . Using dance in Parkinson’s populations, using dance with at risk teens.

That’s also part of the umbrella of dance medicine / dance science. It involves medical professionals working with dancers, dance educators, people like myself, dance scientists. So that’s another aspect of my research.

I love dance and I’m invested in it. And I think dancers, they bring a lot to the table. Working with engineers, working in the sciences, trying to bring artists to have a voice at the table [solving societal problems]. The notion that artists don’t simply need to reside in this little space called ‘entertainment’ or whatever you want to put them in.

We wouldn’t have gotten to this particular innovation solution for this [mobility] device unless I had actually brought this kind of dance lens to it. And that, I hope, can happen more. Just crossing disciplinary boundaries.

. . .

Usually when I’ve done collaborations outside the arts, I would say it’s always been me reaching out to them. . . Me saying, hey, I had this idea, what do you think about this?

I rarely see it go the other way so that in the scientists, the biologists, the physicists, the engineer, the businessperson comes to the dance department and says, you know, you work with human beings and expression all the time, communicating human ideas and experiences, and you work with human bodies. You’re designers in a form of motion. And I thought it would be interesting to bring your perspective to the table on this project.

mlmorris5.wixsite.com/mlmorris

. . .

NPR Science Friday (2016) – A New Spin on Dance

Arts & Disability YouTube channel