By Robin O’Dell

. . .

In Dialogue

Dawoud Bey & Carrie Mae Weems

. . .

Through October 23

Tampa Museum of Art

Details here

. . .

So many things have transpired over the last few years that give new weight to the Black experience in America. The Black Lives Matter protests empowered many artists of color across the nation to speak about and document their experiences. The triumph of living in skin in a wide range of hues has traditionally been undervalued and underrepresented in the history of American photography and most people would be hard pressed to name more than a few Black photographers who are historically known and venerated.

. . .

. . .

The Tampa Museum of Art is presenting the exhibition Dawoud Bey & Carrie Mae Weems: In Dialogue. In a newly expanded gallery, this gathering of over 120 photographs offers retrospectives of two very important and influential photo-based artists weaved together into a complex body of art, sharing themes of race, class, sadness, pain, beauty, representation and power. It is grounded in the Black experience and at the same time speaks to human life and universal conditions.

. . .

. . .

Weems and Bey met in New York City in 1976 and have maintained a friendship and supportive artistic dialogue ever since. They are the same age, both born in 1953, and have become important voices in the modern landscape of the photographic dialogue. The exhibition was organized by the Grand Rapids Art Museum and is curated by Ron Platt.

The exhibition is divided into five themes, which gather images by similar areas of exploration, loosely following a timeline. The first part explores both artists’ Early Work. Encountering them feels like stumbling onto stories of community that have somehow been left out of the conversation. Street and documentary photography from the 1980s with subjects like kids on a boardwalk or people walking down city sidewalks evoke work by photographers Bruce Davidson or Joel Meyerowitz, except these images feature people of color. The glorious normalcy of them makes one realize how little images like these have been part of the canon of photography.

. . .

. . .

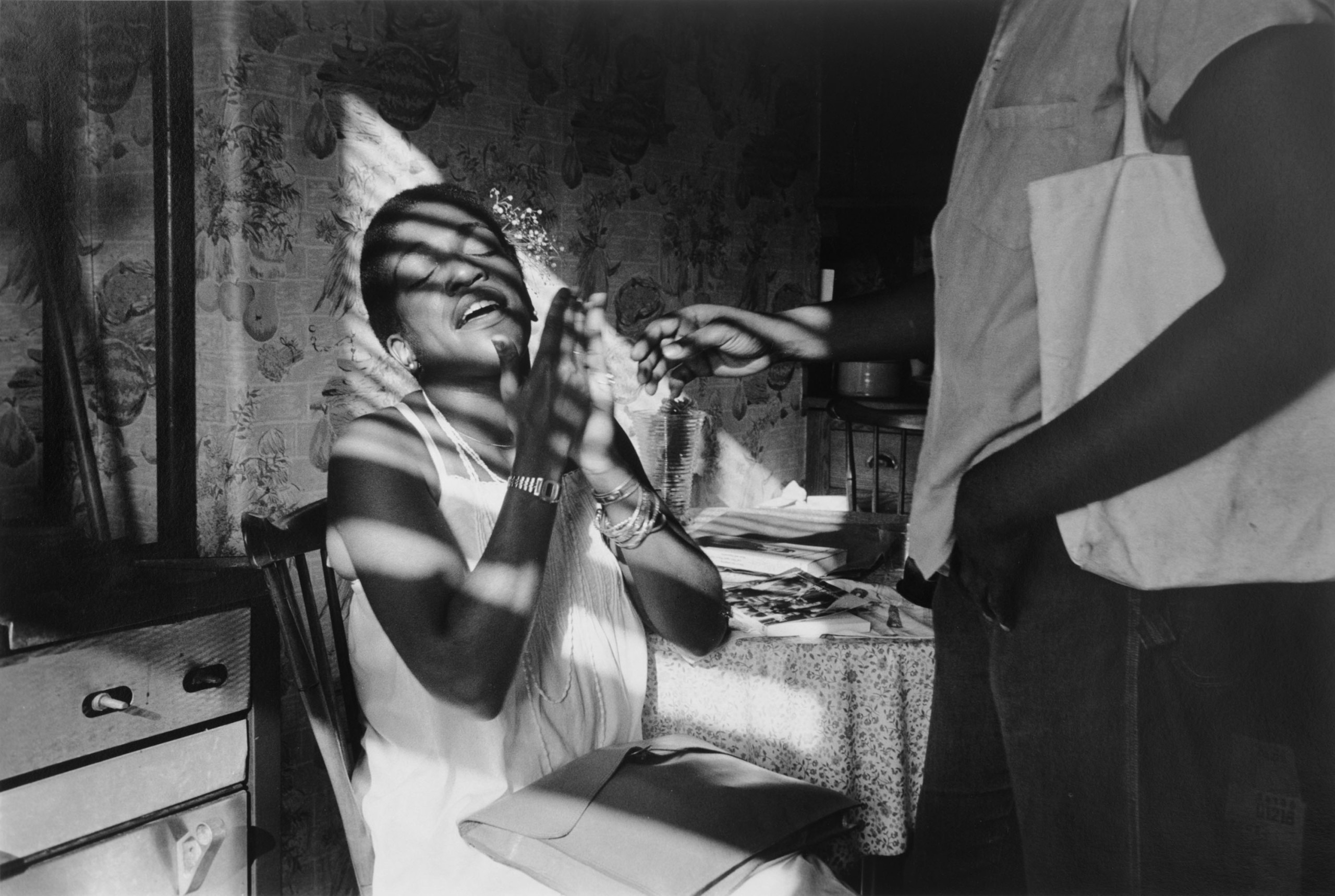

Broadening the Scope allows us to see both artists coming into their own with distinctive voices and methods of representation. Weems turns the camera onto herself as she presents a fictional story of the difficulty of family survival in The Kitchen Series. It is all shot at her kitchen table from a single perspective with varying other characters and props. Her signature trope of adding words to the image is presented through a series of separate texts that loosely correlate with the photographs yet tell a story of their own.

. . .

. . .

I had seen some of these images before individually and found them interesting – but seeing the series made them compelling. Bey’s work transforms from earlier black and white street photography into more formal staged portraits, sometimes brilliantly colored, sometimes presented as multiples and often focusing on young people.

In the section Resurrecting Black Histories both artists explore historical landscapes and cultural experiences. Bey’s giant dark photographs of places in Ohio thought to be locations on the Underground Railroad are hauntingly gorgeous.

In my opinion, these photographs alone make it worth coming to the exhibition because no image in a book or screen could ever compare to the subtle visceral beauty of these prints. The viewer is drawn into the experience of arriving at a place of refuge in the dark of night, with all the fear and excitement that might evoke.

. . .

In Weems’ series From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried, she tackles the subject of how photography has played a key role in shaping racism. Weems appropriates historical daguerreotypes of American slaves that had originally been gathered to illustrate theories of racial inferiority. They are profoundly humiliating. Enlarging them and placing them under red glass etched with poignant script makes them even more difficult to view – part of our collective American history that some people in authority are currently trying to deny or bury.

. . .

and make that history resonate in the contemporary moment?”

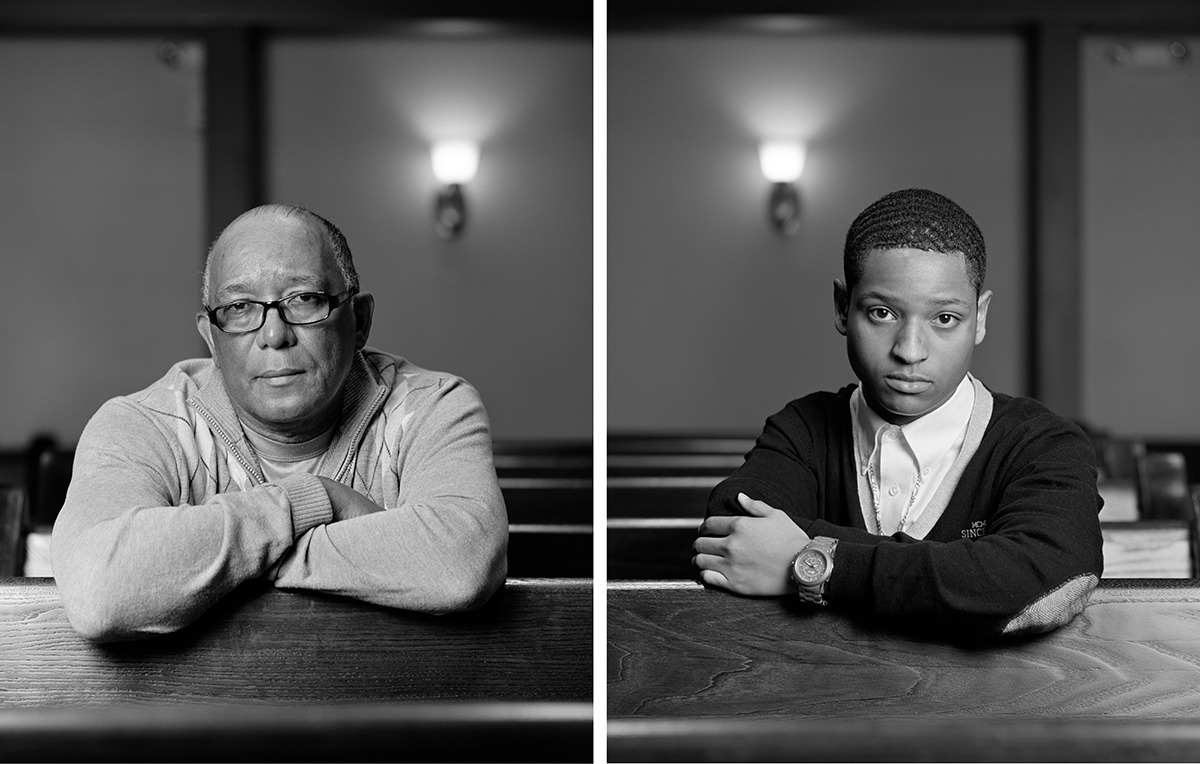

Memorial and Requiem finds both artists exploring 20th century historical events. Bey’s series The Birmingham Project presents large-scale black and white diptychs memorializing the six young Black girls killed in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Alabama in 1963. Photos are paired, images of young people the same age as those when killed with photos of adults the age they would be now, had they survived. The two were photographed in separate settings and have no real relationship to each other, yet bear striking resemblances and evoke the loss the violence created.

. . .

. . .

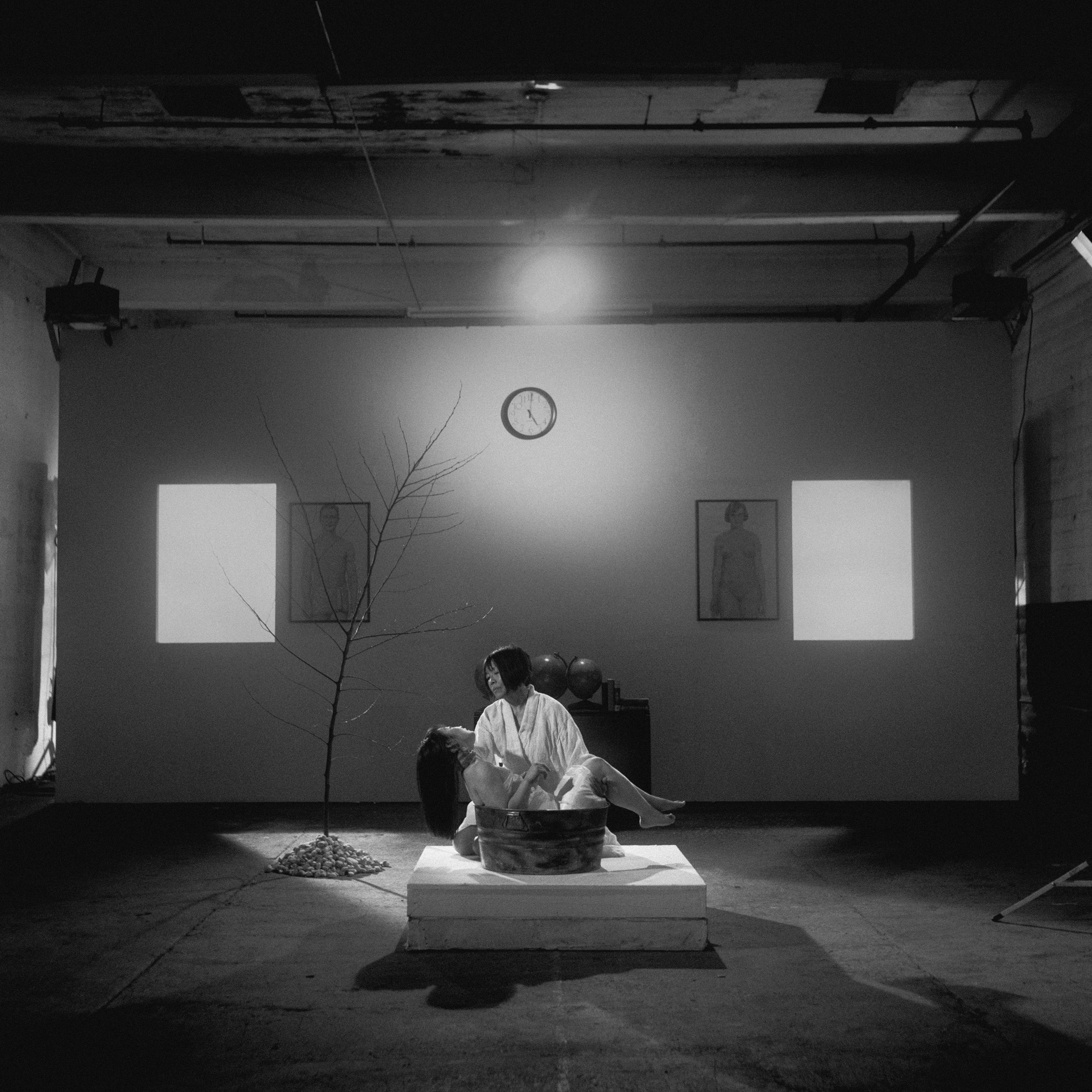

Both artists have videos in this section. Weems’ project features staged reenactments of famous images of the 20th century like those recording the execution of JFK and the funeral of MLK, Jr. She also makes large-scale single images from the series. One is reminded not only of the tragedy, but of the collective memory we share of a single iconic photograph that documents the moment.

. . .

. . .

The final section, Revelations in Landscape, finds the artists returning to ideas from their early work. Bey revisits Harlem in color, which has now gentrified into an area progressively alienating longtime residents. And Weems inserts herself again into the picture, this time into the landscape of Italy, standing majestically among Roman ruins and monuments to a fascist past.

. . .

. . .

Tampa Museum is going through a major transformation. Current spaces are being converted to new gallery spaces, and an exciting new expansion has been announced. Despite all the construction, Executive Director Michael Tomor is continuously trying to figure out how to keep the galleries open.

This exhibition is a must-see for anyone interested in photography, and everyone who wants to see accomplished artists in dialogue about important subjects. This work matters. You should see it and bring every young person you know.

. . .

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dawoud_Bey

tampamuseum.org

. . .