December 15, 2019 | Amanda Sieradzki

Morean Center for Clay Opens The Great Divide

Through December 29

Tue-Sat 10 am – 5 pm

Details here

“A house divided against itself, cannot stand.”

Abraham Lincoln, who would eventually become the nation’s 16th president, famously delivered those words as he ran for the U.S. Senate in 1858. Less than 100 years stands between the converted 1926 Seaboard Freight Depot that houses the Morean Center for Clay and the sage wisdom that spoke against slavery as a nation stared down a civil war.

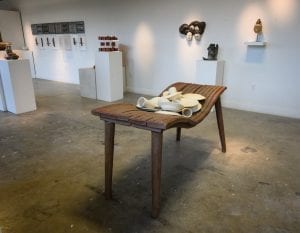

Showcasing the work of 50 ceramic artists, the Morean Center for Clay’s newest exhibition, The Great Divide, opened yesterday. The pieces in the gallery space exist in a fissure similar to the one Lincoln addressed. Narrative, political, aesthetic and structural divides make their presence known on a global scale with works ranging from functional pottery to sculpture, porcelain to wood-fired ceramics.

Internationally renowned-ceramist Bruce Dehnert of the Peters Art Valley Craft Center in New Jersey conceived of and juried the show. Clay Studio Artist Program Manager, Matt Schiemann, connected with Dehnert at a workshop and after many discussions was intrigued by the exhibition’s creative potential.

“It was an open-ended idea, thinking about the politics that are happening now and the division that is happening within ceramics with functional or non-functional routes,” says Schiemann. “There is this giant divide and this is a way to bring those two sides more uniformly together.”

“It is really interesting in terms of the use of clay as a material of the earth because some of the divide is around environmental issues and issues of geography,” adds Robin McGowan, the Morean Arts Center’s Director of Marketing & Communications.

184 artworks were submitted from artists as far away as China and across the bay in Sarasota. The 44 selected works can be viewed and purchased through the end of this month. Thematically, pieces traverse many gulfs and crevasses. Thoughtfully hung near the entrance, Alex Hodge’s Hang in There, I’ve Got You, my Love, tenuously connects two ceramic and wax figures with silver string.

The rescuing figure’s face catches the light as the second figure dejectedly hangs, tangled in the string and cast in shadow. Hodge conjures up familial rifts and fractures of self — or, perhaps from a political lens, families being torn apart as they flee and desperately hang on to one another.

Immediately around the corner is Luke Sheets’ Hold My Beer, a slip cast porcelain and wood piece juxtaposing two sets of praying hands — seemingly referencing Albrecht Dürer’s 16th century ink and pencil drawings — as they cradle a beer can and long-barreled revolver. A few steps away hangs Cindy Leung’s People Talk, which renders two women’s nebulous heads in ceramic, enamel paint and nail polish.

These works are balanced by smaller, functional pieces on pedestals such as current Morean artist in residence, Yeonsoo Kim, with his Listening 2019-3. Covered inside out with intricate black and white creatures, the piece tells a story that wraps around the oblong, ceramic vase.

Similarly, Nick Ngeankoplis’ Tea and Coffee Series | Tomorrow is Going to be Different ceramic tea set delivers an optimistic whimsy in its gray and white mosaic façade. Light to the touch, Valerie Scott Knaust, Director of the Morean Center for Clay, takes a teacup in her hand as she describes its quality and why she fell in love with clay in the first place.

“You look at it and you just want to hug it,” says Knaust. “You know it is hard, but it has that quality of the softness which I find very appealing.”

Clay feels an appropriate choice to mirror the more abstruse topics contained within the idea of our global and human divisions. Despite their hard exteriors, once something is held or contemplated by the mind and eye for more than a few moments, a divide can be examined with renewed clarity and empathy.

Perhaps the largest focal point and example of this is Meredith Knight’s A Brief History of Inequality in America. This piece generates the most conversation and silence. A series of antique door handles in Lucite boxes are hung below metallic squares overlaid with black lines and patterns. One box is frosted while another pattern appears broken.

Could it be referencing open and closed doors or circuits? A divide between digital and analog thought processes? Or is it implying something deeper about the real or virtual rooms behind the doors and who is allowed inside?

“We love the length of time that people spend in the gallery because you can see them trying to puzzle out what is going on,” remarks Knaust as we stand speculating. “Clay is often utilitarian. There is an answer to it. But I love when there is no answer.”