By J. J. Frauenfelder

. . .

Through January 9

The James Museum

Details here

. . .

In collaboration with the Booth Western Art Museum in Cartersville GA, and the Cochran Collection in LaGrange GA, the James Museum of Western and Wildlife Art presents Warhol’s West — a special exhibition intended to “show a different side of Andy Warhol.”

Curated by Emily Kapes, Warhol’s West combines materials from the James’ archives as well as the Smithsonian-affiliated Booth Museum and the privately-owned Cochran Collection. Through revelation and evidence of Warhol’s personal sensibilities, choices of subjects and process, this exhibition highlights the artist’s body of Western-inspired work — culminating in Warhol’s 1986 Cowboys and Indians series, completed shortly before the artist’s death.

Eschewing contemporary political ideology, Kapes smartly curates the exhibition to allow for viewers’ contemplation of a more nuanced American history – and the effect of Warhol’s quintessential Pop Art style as a vehicle for constructing Americana.

Visitors are immediately greeted by a large image of Andy Warhol wearing cowboy boots. Photographs of the artist’s personal inventory display Native American artifacts and crafts. Warhol’s West leaves little room for speculation with such bold visual evidence of Warhol’s affinity for the mythic American West as well as the people and cultures of America’s First Nations.

. . .

. . .

Kapes’ curatorial lens serves to establish the meaning of Warhol’s stylistic choices and provides insight into the calculated nature of the artist’s craft. An entire wall at the beginning of the exhibition is dedicated to a series of 20 processual screen-prints utilizing the image of Sitting Bull from Warhol’s Cowboys and Indians series (1986). On the surface, these serigraphs are a practical display of the screen-printing process. However, they ultimately demystify the mass-produced quality of Warhol’s finished work.

By foregrounding the steps of artist’s process through a series of screen-prints that represent successive technical steps, museum-goers are made acutely aware of an intentionality that is not directly evident in Warhol’s finished Pop Art prints.

With this awareness, viewers are encouraged to consider the artist’s deliberate choices of source images, cropping, composition, placement and color. These initial impressions of Warhol’s West set the stage for guests to view the rest of the exhibition with a sense of perception into the artist’s Pop Art style – as a visual instrument with the power to elevate, or iconify, his subject matter.

Two Warhol series make up the bulk of this exhibition – Myths (1981) and Cowboys and Indians (1986). Museum-goers are initiated into the subject matter by an image of Elvis “in Western garb” from a 1963 show of Warhol’s work that reveals Warhol’s Western-inspired imagery as a “mirror for America to view itself.”

As Kapes points out, Andy Warhol chose a very specific image of Elvis, from the 1960 movie Flaming Star, representing a “triple Americana” of Elvis’ pop celebrity, cinema star and Western cowboy.

. . .

. . .

Warhol’s West not only presents an intimate view of the artist’s choices and personal relationship to this unexpected subject matter – the exhibition reveals snapshots of American life during the artworks’ creation. Most finished screen-prints in the exhibition are accompanied by polaroid facsimiles of their iconic subjects — which shed light on human narratives implicit in Warhol’s art practice.

The polaroids, alongside Warhol’s finished screen-prints, show Warhol’s intentional relationship with his subject is beyond pure voyeurism.

From the American Indian (1976) series, portraits of the Lakota activist Russell Means are visual evidence of Andy Warhol’s purposeful engagement with the leader of the American Indian Movement (AIM).

While apolitical in tone, Warhol’s work with First Nations subjects does achieve a certain reimagination of collective American identity by uplifting the contemporary American Indian activist to the level of popular icon. The American Indian series signifies Americana’s revisioning by highlighting a prominent First Nations’ activist.

. . .

. . .

Warhol’s West is effective in further exemplifying the artist’s late series Cowboys and Indians (1986) in its constructivist approach towards popular representation and Americana. Relative to the rest of Warhol’s work, there is a democratizing effect that takes place within this series. The artist’s Pop Art style is so bold and visually confrontational — yet static – bestowing an equal visual power upon any subject.

In this manner, Theodore Roosevelt, Annie Oakley and Chief Sitting Bull are designed to occupy the same imaginary space, as popular icons in a graphic sphere of Americana.

While Kapes’ curatorial methodology remains speculative, or ambiguous, concerning Andy Warhol’s political inclinations, there is an undeniable transformation that takes place when the artist’s signature style is applied to subjects of America’s First Nations. In some ways, it is in Warhol’s lack of political statement that his work is most ingenious in re-writing history.

. . .

. . .

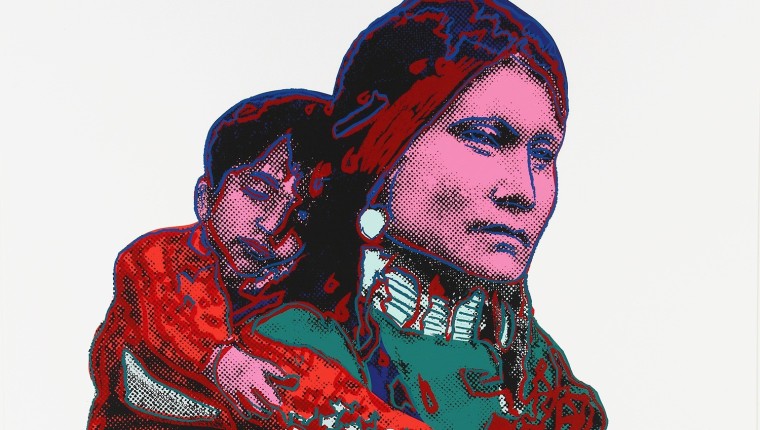

Towards the back of the exhibition is a 1987 screen-print entitled Mother and Child, which shows a cropped image of a woman carrying a sleeping toddler on her back. The source image displayed is a postcard of the same two subjects set in a forested background, accompanied by the caption, “’Bright Eyes,’ Squaw and Papoose.” Effectively, Andy Warhol’s treatment of derogatorily racialized, colonial imagery was able to strip down the layers and manifest a romantic portrait of motherhood in late 19th century America.

Andy Warhol’s work operates in a purely semiotic dimension – as visual symbols. However, Warhol’s West displays the artist’s ability to instigate change in the realms of popular representation.

At its core, this exhibition creates space for museum-goers to indulge, question and fantasize about what it means to be quintessentially American.

. . .