July 6, 2020 | By Margo Hammond

Traveling By Book Through Tampa Bay

. . .

Books can transport us to faraway, exotic places we’ve never seen, but they can also show us new angles of familiar places we thought we knew. Places closer to home like Hyde Park, Tierra Verde, Davis Islands, Palma Ceia, Clearwater Beach, Pass-a-Grille, Indian Rocks Beach, Westshore, St. Petersburg’s 34th Street, Gibsonton, Lake Maggiore, Pinellas Park, Largo, Safety Harbor and Rattlesnake.

Those are the local settings — yes, Rattlesnake is a real place! — for the 15 stories collected in Tampa Bay Noir, an anthology of new crime fiction due out in August.

Edited by Tampa Bay Times book editor Colette Bancroft, Tampa Bay Noir is the latest noir anthology published by the Brooklyn-based publisher Akashic Books. The first, Brooklyn Noir, came out in 2004. There are now more than 81 titles in the series.

“It’s surprising it’s taken Akashic so long to get around to us,” laughs Bancroft. “There so much material here.”

The publisher, she explains, has several established criteria for the series – every story must be an original, set in a distinct locale within each book’s geographic area. The contributors have to be a diverse lot. And they all must have lived (or still live) in the chosen city.

The contributors whom Bancroft has gathered — Michael Connelly, Lori Roy, Karen Brown, Tim Dorsey, Lisa Unger, Sterling Watson, Luis Castillo, Ace Atkins, Sarah Gerard, Danny López, Ladee Hubbard, Gale Massey, Yuly Restrepo Garcés and Eliot Schrefer and Bancroft herself — all have a connection to Tampa Bay.

Bancroft’s own tale is called “The Bite.” It’s set in Rattlesnake, a Tampa neighborhood where Bancroft grew up. Located in near Gandy Boulevard and Westshore, Rattlesnake started out as a town in the 1930s, founded by George End who ran a rattlesnake canning business there. It once had its own post office, general store and snake pit attraction. End died from the bite of one of his own rattlesnakes. His town was annexed to Tampa in the ‘50s.

“Ask most people what the Tampa Bay area is famous for, and they might mention sparkling beaches and sleek urban centers and contented retirees strolling the golf courses year-round,” Bancroft writes in her introduction to Tampa Bay Noir. “But it’s always had a dark side.”

The Tampa Bay Noir anthology follows a long tradition of crime fiction set in this land of fake Gasparilla pirates and all-too-real mob gangsters. In Live and Let Die, one of Ian Fleming’s James Bond books published in 1964, the author sends Bond and a love interest named Solitaire to St. Petersburg to meet up with Felix Leiter, Bond’s counterpart in the CIA. Fleming had visited St. Petersburg with his wife a few years before.

Fair warning: Fleming’s description of the city didn’t win him any Chamber of Commerce awards:

“‘For heaven’s sake,’ said Bond, ‘what sort of a place are we going to?’ ‘Everybody’s nearly dead in St Petersburg,’ explained Solitaire. ‘It’s the Great American Graveyard. When the bank clerk or the post-office worker or the railroad conductor reaches sixty he collects his pension or his annuity and goes to St Petersburg to get a few years’ sunshine before he dies. It’s called ‘The Sunshine City.’”

Leiter ends up losing an arm and a leg in “Sunshine City.”

Tampa’s Ybor City didn’t fared much better in the hands of John D. MacDonald when the granddaddy of all Florida crime writers wrote his very first novel in 1950 and set it there. In The Brass Cupcake, he describes the Tampa neighborhood as “depressed” and mocks local officials who think they can turn it into something that looks like New Orleans’ French Quarter.

Depressed or not, Ybor City wins the prize for the most popular Tampa Bay setting for writers. Lawrence Block opens his 1961 thriller Killing Castro in Ybor (he calls it the “Latin quarter”). Ace Atkins’ White Shadows, published in 2006, is set in 1955 Tampa, with many of the scenes taking place in Ybor. It’s based on the real-life (and gangland killing) of Charlie Wall, an Anglo kingpin with deep ties to the “Latin” neighborhood. Dennis Lehane brings his Boston-born fictional gangster Joe Coughlin to Ybor in Live by Night (2012) and World Gone By (2015), the last two books in a trilogy that began with The Given Day.

Crime though hasn’t been the only inspiration for books set in Ybor. José Yglesias who was born in Ybor City set his first, highly autobiographical novel there. A Wake in Ybor, published in 1963, describes three days in the life of a Cuban-American family in 1958. Paul Wilborn gives us a glimpse of Ybor in the ‘80s in Cigar City: Tales From a 1980s Creative Ghetto, winner of a Gold Medal in this year’s Florida Book Awards. The linked short stories in this collection are fictional but they are based on Wilborn’s real-life experiences. Born in Tampa, Wilborn grew up in Temple Terrace but his maternal great-grandparents, Sicilian immigrants, were married in Ybor. In the ‘80s, while working at the Tampa Tribune, he rediscovered the neighborhood – which had become party central, filled with actors, musicians, street poets and drag queens.

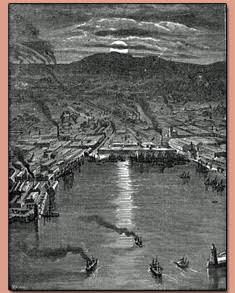

The very first novel set in Tampa Bay was interested in the cosmos. In 1865 Jules Verne, a French novelist best known for such classics as Journey to the Center of the Earth, Around the World in Eighty Days and A Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, set his adventure story From the Earth to the Moon in a place he called “Tampa Town.”

Dozens of writers have followed in Verne’s footsteps, using venues throughout Tampa Bay as backdrops for their stories. The have penned books of fiction and nonfiction, books of humor and romance as well as crime and science fiction. These books provide us with a unique look at familiar spots, a travel guide to worlds just outside our doors. And you don’t even have to get up from the couch.

. . .

TOURING TAMPA BAY BY BOOK

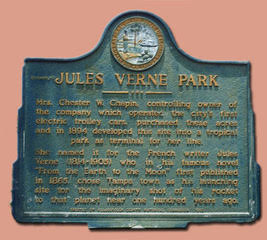

Jules Verne Park, Tampa

(now called Ballast Point Park)

“After coasting along a series of creeks abounding in lobsters and oysters, the Tampico entered the bay of Espiritu Santo where she finally anchored at a small, natural harbour, formed by the embouchure of the river Hillsborough, at 7 p.m. on the 22nd of October… Barbicane has scarcely set foot on shore when three thousand

of the inhabitants of Tampa Town came forth to meet him… Declining ovation, he ensconced himself in a room of the Franklin Hotel.” — From the Earth to the Moon by Jules Verne (1865)

In 1894 Mrs. Chester W. Chapin, the controlling owner of the company which operated the city’s first electric trolley cars, created a tropical park as a terminal for her line. She called it Jules Verne Park in honor of her favorite author. The park’s name was changed to Ballast Point Park in 1920 (ballast is a word used by sea captains for the rocks they pick up to balance their loads).

Alas, now all that is left in the park of Chapin’s tribute to Verne is a plaque.

The plot of Verne’s novel, set in what he called “Tampa Town,” involved an attempt by a Baltimore gun club to send a rocket to the Moon. They choose Florida for their launch. Early editions of From Earth to the Moon are accompanied with engravings of Tampa Town that show the locale “previous” to and “after” the “undertaking.”

Remarkably, 104 years later NASA successfully sent men to the Moon for the first time from Florida, just as Verne had predicted. Okay, he was slightly off on the exact spot — Apollo 11 was launched from Cape Canaveral, 114 miles east of Tampa — but give the guy some slack. He had never set foot in our state. His protagonist Barbicane stays at the fictitious Franklin Hotel. There is a Franklin Street in Tampa and there is a hotel there, but Stay Alfred at 915 North Franklin Street is currently closed due to COVID-19.

More here

La Septima – 7th Avenue

Ybor City

“I jockeyed the car through the traffic in the direction of Ybor City. Melody wondered about it and I told her. The city fathers have, for some time, had the rather vague idea of turning Ybor City into something resembling the French Quarter in New Orleans. But there isn’t enough to start with. Ybor City is what you would get if you took the flavor and atmosphere of one square block of old New Orleans and scattered it, diluted it over thirty or forty blocks of depressed ex-residential, semi-industrial area in any U.S. city. A lot of the best food is served in tile palaces that look like annexes to the men’s room in Grand Central, and you can get the same food next to a patio fountain with colored lights shining on it — if you want to pay the differential.” — The Brass Cupcake by John D. MacDonald (1950)

Located northeast of downtown Tampa, Ybor City was founded in the 1880s by Vicente Martinez-Ybor and other cigar manufacturers. The area attracted immigrants from Cuba, Spain and Italy who were hired by their factories.

By 1929, cigar production reached its peak with 500 million cigars rolled in Ybor. The Depression, however, hit the area hard, sparking an exodus that was accelerated by World War II. By the late ‘70s, the area was virtually abandoned only to be revived in the ‘80s by an influx of artists.

John D. MacDonald and his wife first came to Florida in 1949 to winter in Clearwater. The following year he published his first novel, The Brass Cupcake, set in Ybor City. MacDonald obviously was not enamored with Ybor, but two years later he ended up moving permanently to Sarasota, so he obviously warmed to Florida.

Tampa does make another brief appearance in Bright Orange for the Shroud, MacDonald’s sixth novel, published in 1965 and starring his most famous creation, detective Travis McGee who was based in Fort Lauderdale.

More here.

Lowry Park Zoo

Tampa

“Lowry Park’s very existence declared our presumption of supremacy, the ancient belief that we have been

granted dominion over other creatures and have the right to do with them as we please. The zoo was a living

catalogue of our fears and obsessions, the ways we see animals and see ourselves, all the things we prefer not to

see at all. Every corner of the grounds revealed our appetite for amusement and diversion, no matter what the cost.

“Our longing for the wildness we have lost inside ourselves. Our instinct to both exalt nature and control it. Our deepest wish to love and protect other species even as we scorch their forests and poison their rivers and shove them toward oblivion. All of it was on display in the garden of captives.” — Zoo Story: Life in the Garden of Captives by Tom French (2010)

The zoo began in the 1930s as a municipal department with a small number of animals native to Florida. In 1982 a group of community leaders took over the management from the city, creating a public-private partnership now called the Lowry Park Zoological Society of Tampa, Inc.

The renovated Lowry Park Zoo opened to the public in 1988 with 24 acres. Now caring for 1,100 animals, the zoo has spread to 56 acres of tropical gardens and habitats, offering animal exhibits of endangered, threatened and vulnerable species from Asia, Africa, Australia and Florida. After closing down in March due to COVID-19, the zoo is now open to a limited number of visitors.

Inspired after reading Yann Martel’s The Life of Pi, Tom French, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, first wrote about the Lowry Park Zoo in a series of newspaper articles for the St. Petersburg Times.

More here.

. . .

The Sunshine Skyway Bridge

“This bridge is huge,” I said.

“Jinxed, too,” Angie said. “This is a replacement bridge. The original

Skyway — what’s left of it anyway — is off to our left.”

She lit a cigarette with the dashboard lighter as I looked off to the left,

found myself unable to discern anything in the shroud of falling water.

“In the early eighties,” she said, “the original bridge was hit by a barge.

The main span dropped into the sea and so did several cars.”

“How do you know this?”

“When in Rome.” She cracked her window just enough to allow

the cigarette smoke to snake out. “I read a book on the area yesterday.

There’s one in your suite, too. The day they opened this new bridge, a guy

driving to the inauguration had a heart attack as he drove onto the ramp on the St. Pete

side. His car pitched into the water and he died.” — Sacred by Dennis Lehane (1997)

The Bob Graham Sunshine Skyway Bridge aka the Sunshine Skyway Bridge or more simply the Skyway, crosses Tampa Bay, connecting St. Petersburg in Pinellas County and Terra Ceia in Manatee County. Construction was completed in 1987, replacing an older bridge built in 1954.

In January 1980 that older bridge was damaged by a collision between a Coast Guard cutter and a freighter. The cutter sank and 23 crew members were lost. In May of that same year, another freighter collided with a bridge support during a sudden squall, causing the bridge to collapse, plunging vehicles into Tampa Bay, killing 35 more people. Jinxed indeed.

One of the main scenes of Dennis Lehane’s Sacred involves a car chase and a fatal crash on the bridge. The story, the first to feature Lehane’s popular working-class Boston detectives Patrick Kenzie and Angie Gennaro, is an update of Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep. The detectives are hired by dying billionaire to find his daughter. Patrick’s mentor, a detective named Jay Becker, has already disappeared in St. Petersburg while working the case, so that’s where the two head.

Lehane, who has set three books in Tampa Bay, is a graduate of the Eckerd College creative writing program and founder, along with Sterling Watson, of Writers in Paradise, a writers’ conference held on the Eckerd campus.

The Sunshine Skyway Bridge also appears — or more precisely, disappears —

in Ben Bova’s 2005 thriller Powersat. Along with the Brooklyn Bridge and the Golden Gate Bridge, the Skyway is demolished in a coordinated terrorist attack.

More here.

The Don CeSar Resort Hotel

St. Pete Beach

“At a distance — and it can be seen from bridges and causes more than a mile away —

it seems to rise out of the sea, huge and rosy, like Godzilla in a prom dress: pretty in pink.

And one can be forgiven for imaging that one is gazing at the single biggest, pinkest Big Pink thing

on a planet where, admittedly, not many things manage to be massive in scale and vivid of hue.

At least, not of that hue usually associated with cotton candy, Pepto-Bismo and girlie underwear.”

— “Eight-Story Kiss,” essay in Wild Ducks Flying Backwards, by Tom Robbins (2005)

The Don CeSar opened in 1928. Four years later F. Scott Fitzgerald and his wife Zelda stayed there. Zelda had just been released from a Swiss clinic where she had been treated for mental illness. A letter to Fitzgerald’s editor Maxwell Perkins is headed: Fitz Don CeSar St. Petersburg (for three days only) circa January 15,1932. Both were working on novels at the time – Scott on Tender is the Night and Zelda on Save Me the Waltz (her only published novel). The trip ended sadly with the re-emergence of Zelda’s symptoms.

For years Tom Robbins, author of Only Cowgirls Get the Blues and other madcap novels, made an annual pilgrimage to Florida to visit what he called The Stations of the Cross – stops that included the circus town of Gibsonton, the Dalí Museum gift shop and the Don CeSar.

In his paean to the latter, an essay called “The Eight-Story Kiss,” he admits he never spent a night in the hotel on St. Pete Beach, but when he’s in the area he goes there to “experience the pinkness.” The hotel, he says is “a shrimp cocktail for the eyes,” a place with a bar that “inspires the consumption of strawberry martinis” or the “quaffing of pink ladies, the favorite libation of pink-haired ladies who coif pink poodles, a breed of beast not entirely absent from the hotel premises.”

More here.

Trinity Lutheran Church

St. Petersburg

“GW believes in service. When he got off the streets in 2006, heturned back around to help others up after him. Not everyone does that.” — “The Mayor of Williams Park” in Sunshine State by Sarah Gerard (2017)

Trinity Evangelical Lutheran Church at 401 5th Street North in St. Petersburg began in 1911 with 18 charter members who met in a room over a garage on 2nd Avenue and 2nd Street South. The church moved to its present location in 1924.

For years Trinity has been involved in assisting the settlement of displaced persons and refugees and feeding the homeless. Before COVID hit, the church had been serving “Loaves and Fishes” breakfasts for the homeless every Saturday morning. According to the church’s website, at times, attendance reached over 200.

To research “The Mayor of Williams Park,” included in her first book of essays Sunshine State, Sarah Gerard worked with Trinity to distribute food to the homeless who were living in the park in downtown St. Petersburg.

A graduate of the Pinellas County Center for the Arts at Gibbs High School, Gerard was the 2018-2019 writer-in-residence at Sarasota’s New College. As a teenager she worked for the organization called Food Not Bombs. Her column Mouthful, written ten years into recovery from anorexia and bulimia, chronicled her relationship with food. Her new novel True Love is out this week from Harper Books. It is set, in part, in “the burned out suburbs of Florida.”

More here.

Open-Air Post Office

St. Petersburg

Listed on the National Register of Historic places in 1975, the post office in downtown St. Petersburg, housed in a Mediterranean Revival building, is the nation’s first open-air post office. It’s been in continuous operation since its dedication in 1916.

The post office is where Truman Kicklighter gets his mail. Kicklighter, a former AP reporter, now retired, is the sleuth in Lickety-Split and Crash Course, mysteries Kathy Hogan Trocheck has set in her hometown.

The first opens in the Ponce de Leon room at the Fountain of Youth Residential Hotel where Kicklighter lives. He is reading the St. Petersburg Times. The Fountain of Youth Residential Hotel sounds a lot like the Princess Martha at 411 1st Avenue N (which operates as a senior living retirement residence), but it could also be the old Dennis Hotel at 326 1st Avenue N (now the Williams Park Hotel). Both are just down the street from the city’s famed open-air post office.

Trocheck has published 24 novels, 10 mysteries under her own name and 14 bestselling novels writing since 2002 as Mary Kay Andrews. Last year Andrews published one set in Tampa Bay. It’s called Sunset Beach, described as “a charming but storm-damaged eyesore now surrounded by waterfront McMansions.”

More here.

Grand Central District

St. Petersburg

Grand Central is an artsy district between 1st Avenue North and 1st Avenue South two miles west of downtown St. Petersburg. The area is chock-a-block with creative businesses – including two new bookstores, Tombolo and Book + Bottle – and is especially known as gay-friendly. The city’s annual St. Pete Pride event is held here.

Author and glass artist Cheryl Hollon, a native of St. Petersburg, sets her 2015 mystery Pane and Suffering in one of those creative businesses – The Webb’s Glass Shop, which is a stand-in for Grand Central Stained Glass, an actual shop on Central Avenue.

Called a cross between a cozy and The Da Vinci Code, the mystery is the first in a series starring Savannah Webb, a Seattle glass artist who returns to her hometown of St. Petersburg to settle the estate of her father who founded the glass shop. Webb stays on, which provides Hollon with fodder for five more books in the series – Shards of Murder, Cracked to Death, Etched in Tears, Shattered at Sea and Down in Flames (published last year).

The books provide a tour of the district and beyond with stops at Haslam’s Book Store, St. Petersburg History Museum, the Queen’s Head, Cappy’s Pizza, Mazzaro’s Market and the Warehouse Arts District.

More here.