Story and Photos by Tony Wong Palms

. . .

A (Short) Visual History

of Poverty in the United States

. . .

Through March 4

Free

USF Contemporary Art Museum

Details here

. . .

There’s religious art, environmental art, still life art, court painters’ royal art as in Velázquez for King Philip IV of Spain… but what is poor people’s art?

Poor People’s Art came up as the title of an exhibition at the USF Contemporary Art Museum (CAM) that opened in January.

There’s no specific category for “poor people’s art” in art history books, but plenty of artists do engage with issues raised in this broad category head-on – sometimes also called protest art, activist art or resistance art.

One notable artist is Käthe Kollwitz, 1867-1945, providing empathy and advocacy through the strength of her stark etchings, woodcuts and lithographic depiction of women, the downtrodden, oppressed and war victims during the first half of the 20th century.

A riff on the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign, the exhibition Poor People’s Art with the subtitle, “A (Short) Visual History of Poverty in the United States” responds to injustice due to racial, economic disparities and messy political discourse in the second half of that century – more specifically The Poor People’s Campaign of the Civil Rights Movement and following years.

This campaign was a mass protest planned by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to bring the plight of the poor to the doorsteps of the nation’s leaders by occupying the National Mall in Washington DC.

Cut short by his assassination in April 4, 1968, King’s vision was carried forward by the Reverend Ralph Abernathy and other leaders of the Civil Rights Movement, mobilizing people across the country.

For five weeks, from May 12 to June 24 in 1968, people set up camp at the National Mall, christening the encampment “Resurrection City” and bringing their demands for employment opportunities, fair wages and equal housing.

In the exhibition are 57 works from 18 artists, plus over 30 placards created by USF students, faculty and staff inspired by the protest posters used in the original Poor People’s Campaign.

a Virtual Tour is available here

and a Spotify playlist

On CAM’s exhibition banner and the exhibition catalog title page (the fully illustrated catalog is free to all visitors and the digital version is downloadable) is a contemplative image of flutist Lloyd McNeil playing at one end of the Lincoln Memorial Reflecting Pool with the Washington Monument at the other end.

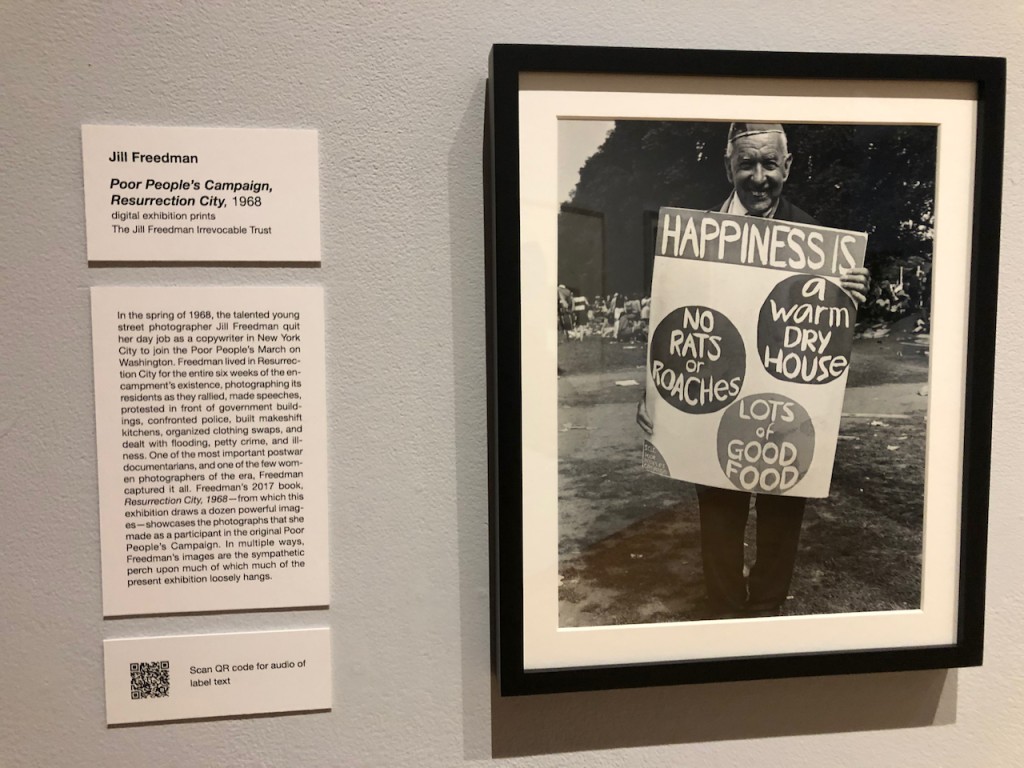

Taken by photographer Jill Freedman during the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign, the image very much recalls the massive 1963 March on Washington where Dr. King gave his immortal “I Have a Dream” speech.

Eleven other images from Freeman are in the exhibition. While there were other photojournalists capturing headlining moments, Freedman’s photographs were unique and in-depth – she was there as a participant, living the duration in the encampment, developing relationships, capturing the immediacy of the day to day, including the “frank and unromantic” moments.

Her images first appeared as part of a photo essay on the Campaign in LIFE magazine.

Besides Freedman, works of two other artists directly reference the Poor People’s Campaign –

Three pieces from Corita Kent – one of which, a 1968 lithograph poster was actually commissioned for the Poor People’s Campaign’s March On Washington.

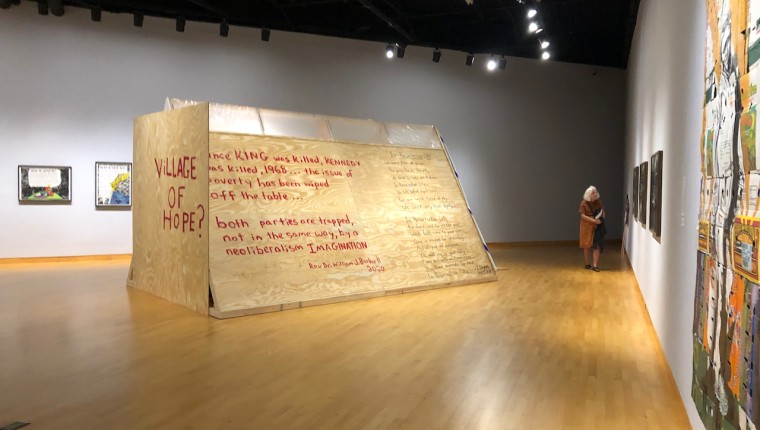

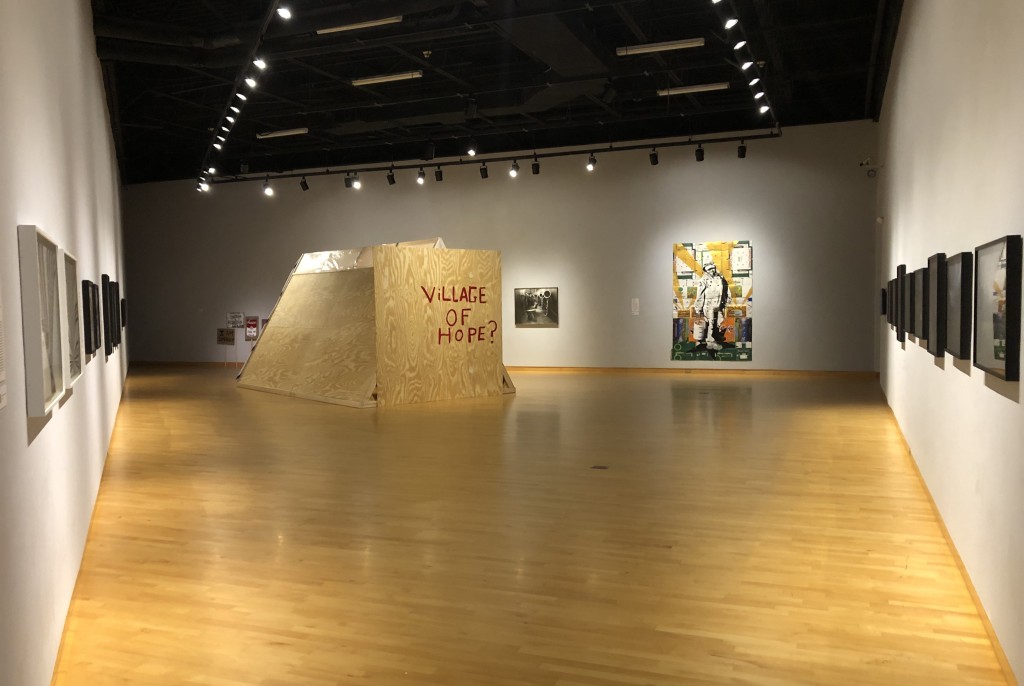

And visual artist and USF professor Jason Lazarus’s interactive installation Resurrection City/Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival, first exhibited in Chicago’s Co-Prosperity Sphere in 2018. The work recreates the plywood tent-like structures erected at Resurrection City. Inside, literature is displayed – including a copy of that LIFE magazine article – and a QR code for visitors to dive deeper into this campaign and related history.

Here’s an article from the The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford, with a photo of of Rev. Abernathy and Coretta Scott King sitting in one of Resurrection City’s plywood tents.

The ’60s was a moment of generational awareness and activism where the understanding of human rights grew and encompassed a greater community of disadvantaged people and minorities who have lived, built and sustained this country, yet are denied its prosperity, benefits and freedoms. The Poor People’s Campaign highlighted this by involving all people regardless of race, ethnicity and belief.

One such group is documented in CAM’s Lobby Gallery with a collection of eight photographs by Hiram Maristany telling the story of the Young Lords Organization (YLO). Emerging from a Puerto Rican street gang this become a community organization advocating for equal access to education, health care, housing and employment.

Founder José “Cha-Cha” Jiménez modeled it after the Black Panther Party, holding free breakfast programs and adopting a similar 13 point program in 1969. Established in Chicago, the Young Lords expanded to New York and other cities, and formed coalitions with other organizations.

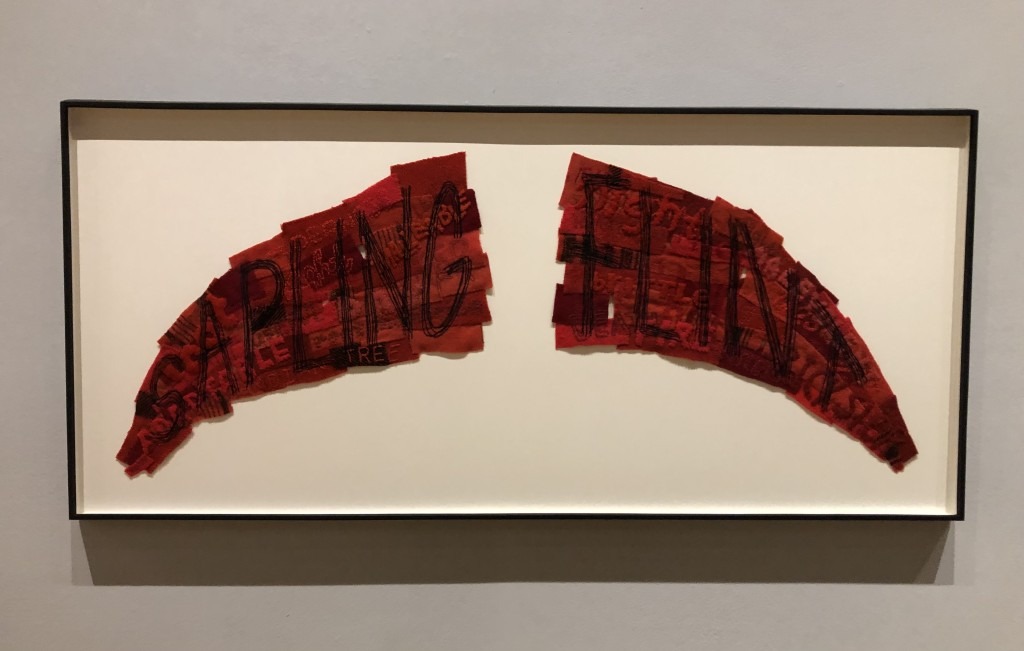

These photographs, selected by another artist in the exhibition, Miguel Luciano, whose two pieces are also in the Lobby Gallery. The People’s Pulpit and a banner from the public art project, Mapping Resistance: The Young Lords in El Barrio demonstrate that while YLO existed only a few short years, their work and ideas are not lost, and are carried on by a new generation, which Luciano represents.

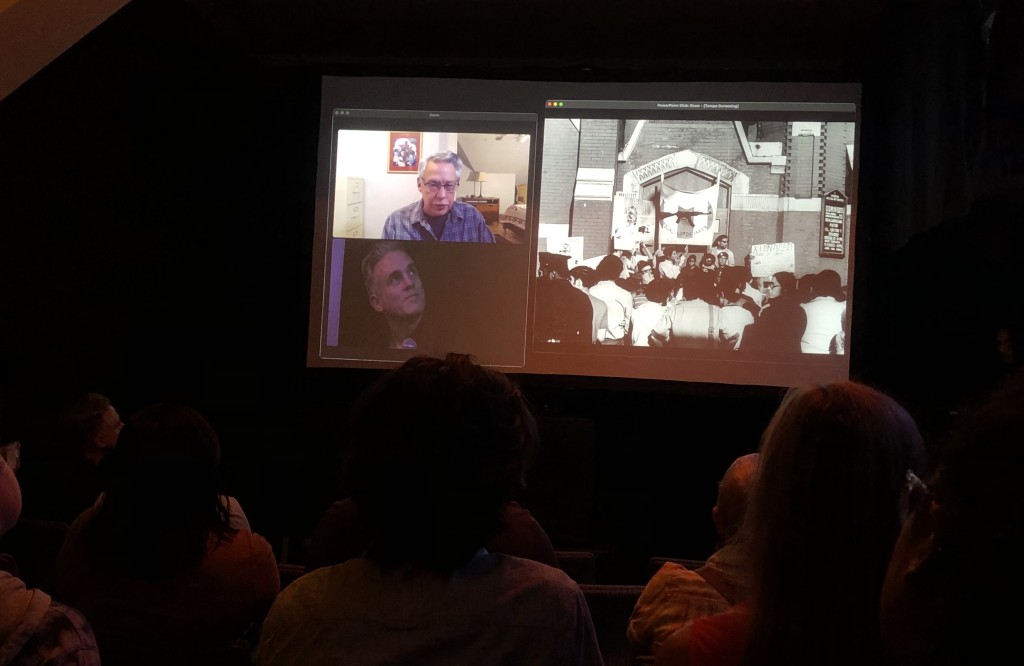

As part of the expanded knowledge projects CAM develops for its exhibitions, Luciano and CAM’s Curator of Education, Leslie Elsasser, hosted a film night showing El Pueblo se Levante (The People Are Rising) at Screen Door: Ybor City Microcinema, documenting YLO action in New York in the late 1960s.

After the screening, Luciano moderated an enlightening Zoom call with Juan Gonzalez, former YLO Minister of Education in New York, now broadcast journalist and frequent host of the television program, Democracy Now with Amy Goodman.

In 2021, The Reverend William Barber II and the Reverend Liz Theoharis launched The Poor People’s Campaign 2.0 bringing the fight against poverty to present day America.

CAM’s Leavengood Gallery reflects a new generations of activists and artists responding, adding their voices to support, and advocating for the poor and oppressed in many forms.

One means of support is simply recording stories which certain political fractions and demographics try to forget, or deliberately ignore and erase.

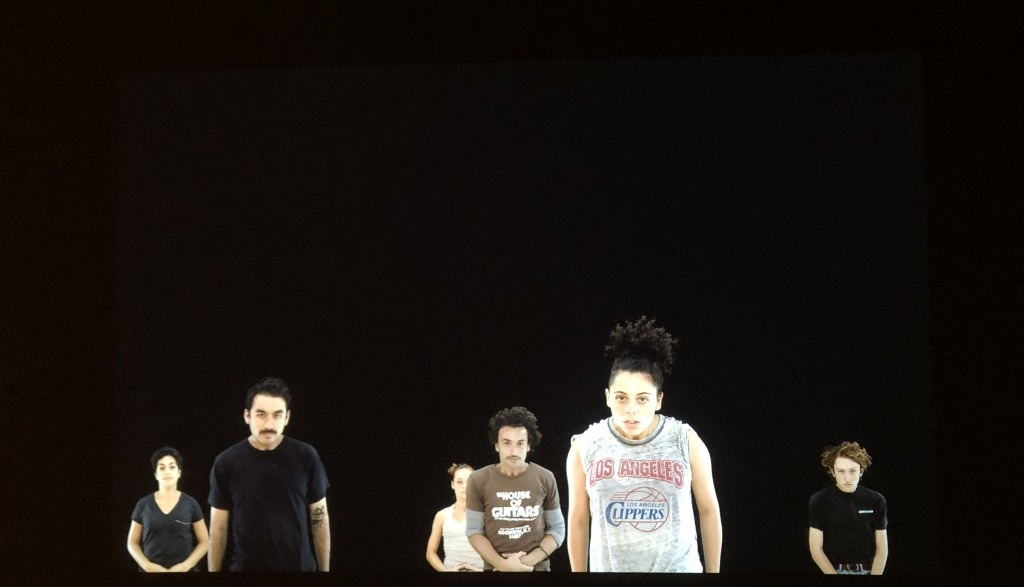

One story I did not know, and learnt while looking at Nina Bergman’s row of brutal photographs and video showing scars, deeply etched faces, and landscapes, is that of the Arthur G. Dozier School for Boys, a reform school operated by the State of Florida until 2011, really more a forced labor camp where inmates are beaten, raped and enslaved.

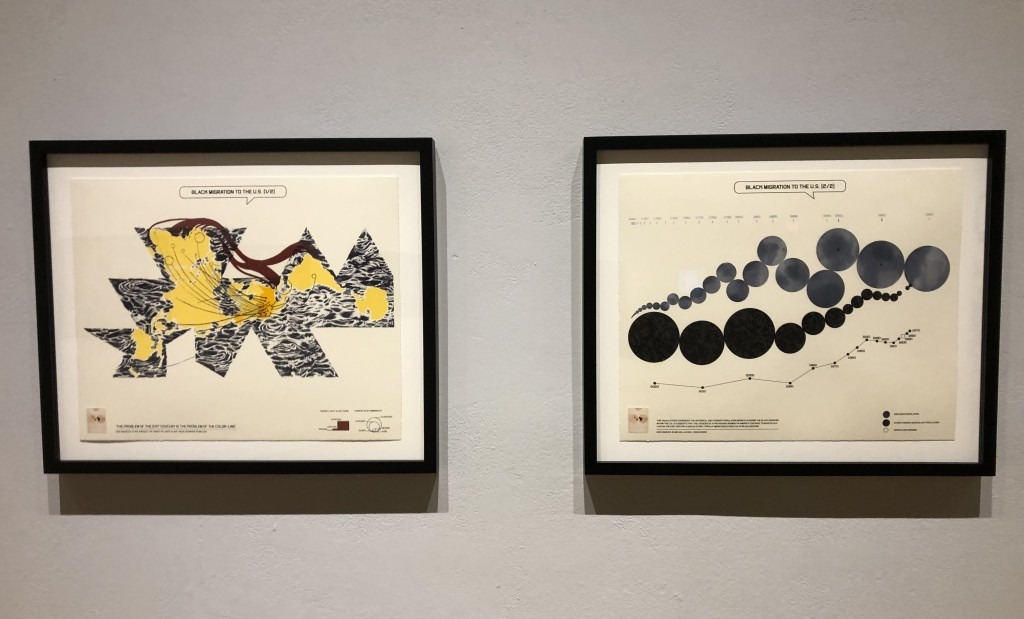

This “reform school” is a legacy of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade as illustrated in two ironically visually appealing graphs, titled Black Migration to the U.S. 1/2 and 2/2 on the opposite wall of the gallery, by William Villalongo and Shraddha Ramani, based on W.E.B. Du Bois’s research data on global migration of Black people.

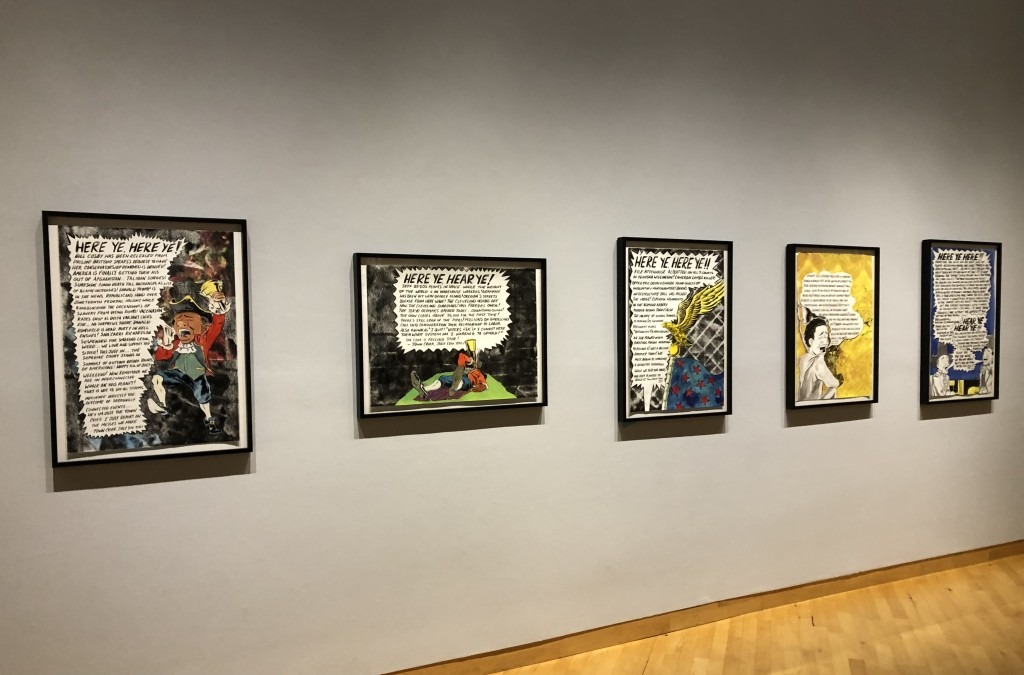

On that same wall, perhaps the most contemporary piece in terms of content is Mark Thomas Gibson’s Town Cryer series – “one part Twitter feed, one part protester, and one part interior monologue” For the older generation, this series is direct offspring of the satirical Mad magazine with its old school illustrations and speech bubbles commenting on current events.

For example, “HERE YE, HEAR YE! Jeff Bezos floats in space while the weight of the world is on warehouse workers! Germany has been hit with deadly floods! Oregon’s streets buckle from heat wave! The Cleveland Indians are now the Cleveland Guardians! Hell Freezes over!…”

Exhibition curator Christian Viveros-Fauné was sensitive in his selection of each artist’s work to build a cohesive dialogue on this long and complex protest history of the poor and oppressed.

Each artist and work link to each other through history and social context, and deserve much more than what this article can articulate. But writing cannot replace entering the exhibition and physically encountering the works.

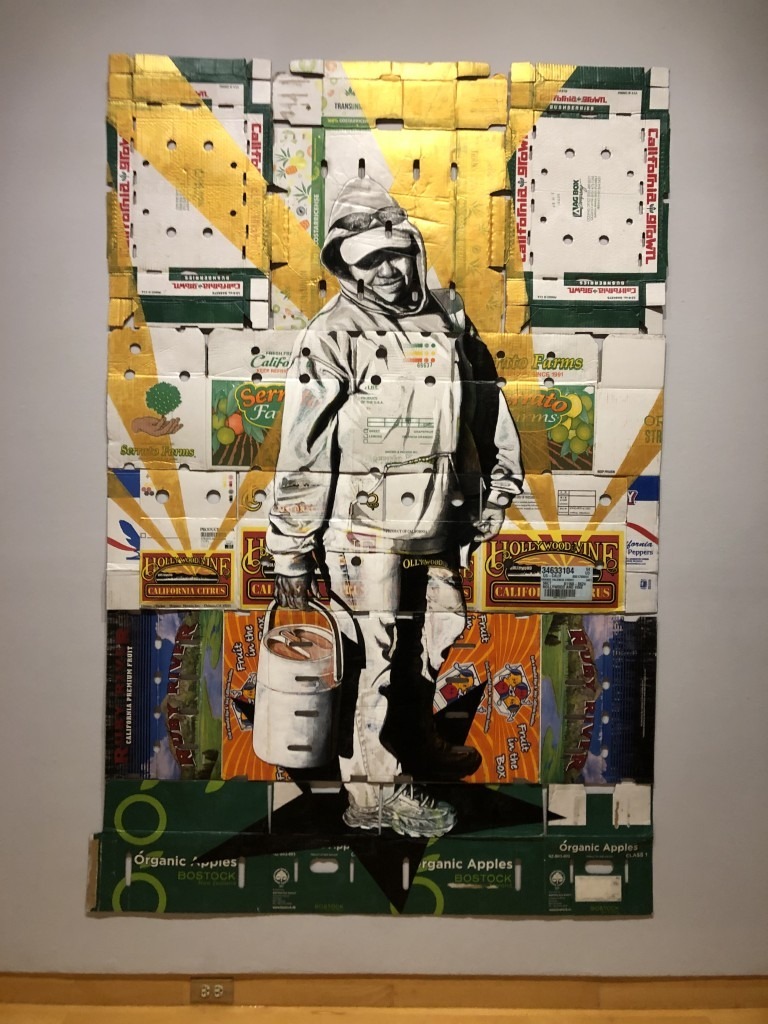

Narsiso Martinez’s Hollywood and Vine (2022) highlights disenfranchised immigrant farmworkers – painted on discarded cardboard boxes used for shipping oranges and other fruits by industrial growers.

Martinez’s use of materials makes an interesting aesthetic connection with subtle social commentary to another piece in the exhibition, that of Robert Rauschenberg’s Made in Tampa print from old cardboard boxes. Rauschenberg has always made art from common materials that surround our everyday life, stuff considered valueless and casually cast away, like the poor among us.

In the early ’70s he made a series of wall sculptures from discarded cardboard boxes (Last exhibited at the Menil Collection in Houston in 2015). Consciously or not, Martinez has reanimated this same material, infusing it with new layers of social concerns and controversies.

This exhibition is like a cherry bomb. A cherry bomb is a bit larger than its eponymous fruit with unexpected large explosiveness, causing safety concerns and ultimately banned in 1966.

Hopefully, like Käthe Kollwitz’s art, this “short” visual history, and the art within, has an equally long explosive reach and continued potency.

. . .

. . .