December 2, 2019 | By Victoria Jorgensen

Witness at Tornillo

December 7 at 11 am

Free

Tampa Theatre

RSVP here

“If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?”

This century-old philosophical question about observation and perception directly applies to the story of Josh Rubin and the documentary Witness At Tornillo.

The Filmmakers

Carbon Trace Productions Executive Producer, Andy Cline and his team traveled to Brownsville, Texas in 2018 for a National Day of Protest, where they met Josh through a friend of a friend. The next day, they traveled to Tornillo Detention Center, a temporary tent city created to detain immigrant children at the border.

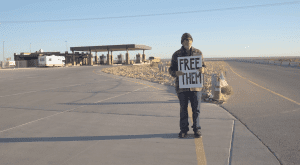

The desolate facility, operated by BCFS, a global network of nonprofit organizations operating health and human services programs on behalf of the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Refugee Resettlement was in the middle of nowhere. When they arrived, Josh Rubin was standing there holding his cardboard sign “FREE THEM.”

Andy and crew were there to protest, but decided to do a quick hotel interview with Josh, not knowing how they would use it. Josh turned out to be an incredibly interesting subject who not only talked about protest, but followed with action — there was the story.

Other people influenced by Josh’s actions showed up to protest and that was an even better story.

Andy wants people to be outraged and spurred to action by this powerful story of the power of an individual.

The “subversive act of seeing” is the idea that observing anything changes it. You are seen watching and that affects the actions of others. Josh showed up by himself with one sign and influenced many to become “witnesses” which eventually led to the closure of Tornillo and other detention centers.

The Story

Since the 2016 election, there have been massive changes in immigration policies including the most apparent, separation of families at the border. This policy created a wave of unaccompanied minor children at the US Southern border, which lead to the creation of remote detention centers in places like Tornillo, Texas and Homestead, Florida.

President Trump’s statement, “These aren’t people, these are animals!” and his zero tolerance immigration policies framed an acute, mammoth crisis at the border. The U.S. government separated thousands of families and drove a wedge between ideologies of the American people.

Joshua Rubin traveled from Brooklyn to Tornillo to protest because he was “tired of sitting and watching the TV and yelling at it!”

. . .

In the film, Josh says, “The border between Mexico and the U.S. is made by a not very wide, dirty river. Coming together at the edge of that river and asking for refuge are people who are desperate enough to leave their homes and come and ask for help. Instead of opening our arms and offering them help, we started putting them in jails. We started separating families. It just seemed so horrendous, I figured I had to come down to the front lines here to the struggle against that!”

Josh stood with his handmade cardboard sign, motioning to anyone who passed by that this was the place where children were held, calling for their freedom. He continued his protest for two weeks before returning to Brooklyn.

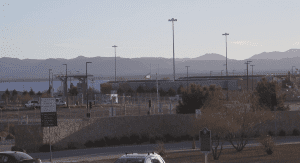

He returned to Tornillo in four months with a motor home which he parked near the border patrol station. He stood in the middle of the desert with his sign, observing the expansion of the facility, trying to learn more about what was going on, on the other side of the fence. The guards, who were paid two to three times more than any local job, overcame issues of conscience and made his presence as difficult as possible by continuously calling the sheriffs and local farmers, making up stories about Josh interfering and trespassing on private land. Soon, the sheriffs stopped showing up as they could find no proof.

Josh microwaves soup in his motor home as he states, “Certain things happen in the world that are affected by people looking at them. It’s kind of a quantum notion, right? If we observe this, it changes the quality of it. People inside now, know that they are observed.”

The U.S. government spent over $750 per day per child to run the Tornillo facility. Everything had to be trucked in including water and generated electricity.

“It’s my hope that witnessing brings about that art of reflection that leads to the question I really want people who work here and support this financially and the government that makes this possible [to ask]. It’s the idea that people can look at themselves and say, ‘I might not be doing something right, I might be doing something really wrong.’”

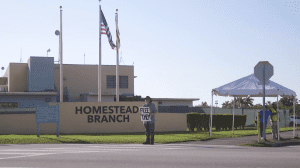

Slowly, people began to show up and protest with Josh until the facility closed in January 2019. One month later, Josh left his home in Brooklyn again, to travel to another detention facility in Homestead, Florida, operated by the unlicensed, for-profit corporation Caliburn.

Caliburn operators came up with a plan to provide a stock offering which was then canceled after it was reported in the New York Times. Former White House chief of staff John F. Kelly was on the board of Caliburn.

There’s no denying and in any discussion you get to the point where people generally admit that being in a place where you can’t leave and you can’t be with your family and you can’t touch anybody else, and you can’t talk to the people you want to or hang out with the people you want to hang out with, makes it a prison. And a prison is not a good place, even with ice cream. – Joshua Rubin, Witness

Find out more about

Witness to Tornillo here

Artists Reflect on the

Radical Act of Seeing

Helen Hansen French

I worked with Your Real Stories, telling Jasmina Kuljanac’s story through dance.

Jasmina was born in Yugoslavia and is from the Bosnian region. When she was nine her family left Bosnia as refugees (minus her dad, men weren’t allowed to leave). She lived in Germany and then moved to the United States when she was 15. At the time she was interviewed she had been living in the US for 18 years.

When I first read Jasmina’s script I was struck by how matter of fact she was regarding some the things she had seen and experienced. Just reading about her childhood experiences was difficult for me — living them seemed unfathomable. Yet, I knew that I wasn’t reading fiction, I was hearing the truth of another woman’s life.

When I first started working on movement for Jasmina’s story I was very intimidated and concerned that I wouldn’t truly “see” Jasmina and that I would get caught up in my own emotional response to her experiences. But as I worked through my own doubts I saw more clearly how valuable empathy is.

Beyond sympathy, empathy propels you to a deeper understanding of a shared humanity and reveals places in your soul that are yearning to connect with others. When I can connect with others and truly “see” them an authenticity exists that goes beyond words, it is transcendent.

I think the phrase “the radical act of seeing” is very apt. Humanity is all interconnected and when you truly “see” others — live, in person, and hear their stories — I suppose that is radical and an act of protest.

More on Helen Hansen French’s work here

Saumitra Chandratreya

. . .

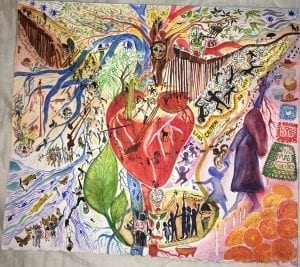

We all have agency. Being able to protest an unlawful, immoral policy is one such agency. I am interested in exploring this through my art because that is my most effective way of affecting change right now.

What I find particularly poignant is the availability of information through various channels, many legitimate and some, untrue. This information compels me to make sense of larger power structures.

I am forced to respond to human rights violations such as the inhumane and barbaric family separation policy of the current Administration, because of the national media attention that this policy commanded. We, as residents of this nation were able to know about the suffering of the people who crossed the border seeking better lives and asylum for themselves and their families.

Even though I am not witnessing the horrors of this policy firsthand, the experience of reading, seeing, watching and consuming news about the policy has compelled me to make work about the forced separation of families at the border. Via still and moving image, and narratives of journalists, activists and congresspersons, I am able to witness, understand and absorb the deplorable, subhuman conditions in which this administration is caging people. This situation needs me to carefully and delicately handle the information and it requires me to clearly see the facts. Seeing this information clearly and with focus enables me to determine symbols that I can use as focal points in my composition.

Stars & Xenophobia, 2019 is an installation which uses various strong symbols that I saw in the images and videos. It uses a tea-dyed United States flag as a backdrop on which the headlines about the family separation policy are hand screen printed repeatedly, to recognize that all Americans in this democracy are equally responsible for the actions of our government.

I also printed names of two children who had died in the CBP custody when this installation was conceived – Jakelin Caal Maquín and Felipe Gomez Alonzo.

In front of the flag, on a pedestal draped with emergency foil ‘blankets,’ sits a replica of the White House. The core structure was fabricated from sides of a toddler’s crib. One of them is woven with tape made from the paper-thin foil. It is neatly woven and opaque, representing the neat, clean and opaque structure of this vile policy.

On the other side, the foil leads to a much more emotional image where the bars of the crib imprison clothing, shoes and stuffed animals symbolic of the children trapped within. The cold, paper thin foil ‘blankets’ are their only comfort. The intensity of the installation is embellished by the viewer, having to step into an enclosure of fencing and barbed wire in order to view the installation.

Making this installation was cathartic. Through it I expressed images and symbolism which enabled viewers to absorb the gravity of this injustice. This installation was publicly shown at the ArtsXchange in St. Petersburg in February 2019.

Ana Maria Vasquez

“It’s witnessing, it’s accompanying what’s happening.”

Painter Ana Maria Vasquez visited the Supreme Court last month for their crucial case that decides whether a U.S. Border Patrol agent is liable for the death of a 15-year-old boy in Mexico, that he shot from El Paso. She was in D.C. to watch.

Ana Maria draws on the wall with her hands. “I would paint the three women judges, with roots. And stand in front of the Supreme Court and hold it up so they can see the judges harvesting good instead of pain, blood, separation, sadness — all that is being harvested right now, because there’s no law to stop this.

“But if the law stands with the people? Sería increíble. But of course they don’t want to make that decision because that would admit they were wrong, they made a mistake.

“The decision is not just for the families, it’s for the whole countries. Which seeds are you going to plant? You have planted seeds of violence, but you have the chance today to plant the seeds of justice.

“Be just, that’s all. It’s not like you’re going to fix all this miraculously.

“Harvest is the key word. What are you going to harvest?”

Bob Barancik

I have been thinking and imaging the plight of refugees for a long time.

Refugees by the Shore series – Graphics & Haiku

Seeking Shelter – Video

creativeshare.com/exhibits/refugees-by-the-shore