Alert! Longer form content ahead (1900 words-ish)

As I was trying to hunt down some media files in old emails, I came across a piece of writing I did for grad school in 2017 that I had emailed myself a draft of. I thought I had lost most of my grad school writing because of a confluence of unfortunate events (hard drive crashed, back-up USB drive permanently damaged, didn’t store all the stuff in the cloud, ASU changed their online platform the year after I graduated so I can no longer access my submitted work). But here was this draft, in its final stages. It’s the first paper I wrote for my master’s program in sociology at Arizona State for a class related to diversity/intersectionality and is written in the form of personal narrative. It was my first time synthesizing aspects of my formative years as a way to understand how I was forged from those experiences, from my own perspective. With my artwork, I do not feel compelled to explain or put a lot of words and context to it. But this is writing! And it’s a personal essay!

So, although this is not directly art related, it is an origin story germane to who I am as both a person and an artist and is part of the initial wellspring from which everything originates.

The Freedom of No Identity: Finding Connection Through Diversity (May 30, 2017)

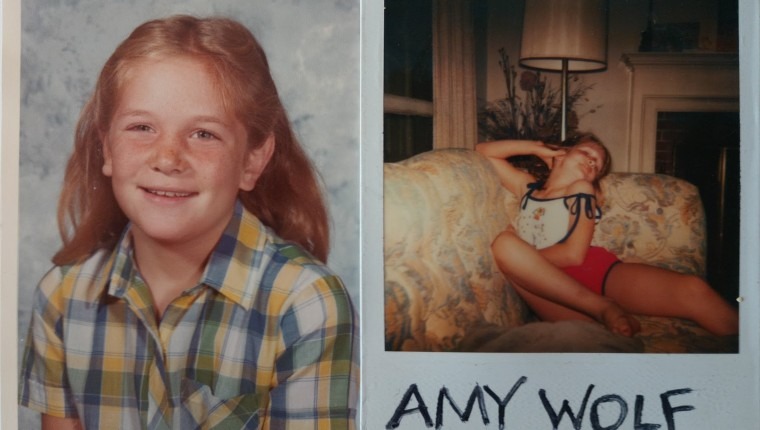

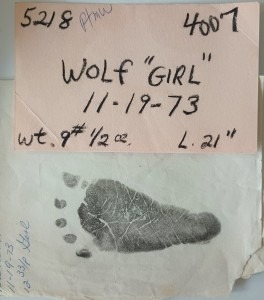

My full name is seven letters: A.M.Y.W.O.L.F. I have no middle name. I couldn’t calculate the amount of hours I spent as a child assigning different middle names to myself, or the time I spent writing my self-created names over and over again to see what each one looked like, felt like, and if it projected an impression of me I was satisfied with. I might mentally adopt one name for a while, then change it when my first choice lost its appeal. Everyone had a middle name. EVERYONE. The failure to be second-named was my first experience feeling like there was a fundamental flaw in my personhood. From a child’s perspective, this denial of a middle name sent the message I wasn’t of value enough to be given one. That feeling of deficit caused me to glorify “the middle name” out of proportion, and envy everyone else who had this secondary, seemingly well-considered and deeply meaningful, component to their identity.

Chen states that our given name operates as a symbol of our identity which overlaps the individual and cultural aspects of who we are, as well as the personal and political (2016). As a five or six-year-old, I just wanted a middle name. I didn’t understand that I was wrestling with concepts of personal identity and desperately seeking connection; a theme that would consistently arise throughout my adulthood. My name-seeking was the first symptom of the intangible disconnection I felt. I would later come to terms with the invisible threads that wove together my story, shaped my experience, and informed my unique relationship to the world.

I wouldn’t know until I was eighteen that the reason I grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area, on the opposite coast from any family, was because my parents had fled the east to escape shame and familial disdain over their being together. My mother was 42 when I was born in 1973 and my father was 21. I was the product of the affair they had while my mother was married with children still in the home. She left her family to be with my father; a union that quickly fell apart in California when my young father’s drinking, mental illness, and abusiveness were brought to the surface. My mother never dated again, or remarried, but provided a middle-class life for us as a nurse. She was a child of the depression and lived without introspection or self-pity. Although mom made a wildly unconventional, scandalous (for the time) life choice, she self-identified as a Roman Catholic daddy’s girl who was crowned the queen of Warren, PA, was voted most popular in high school, and who went off to marry her high-school sweetheart, living the conventional life expected of her (until she didn’t). She didn’t smoke. She didn’t drink. She didn’t swear. I maintained forced visitation with my father who was an emotionally violent, anti-social problem-drinker. He never had a phone and rarely had a regular living arrangement. He had conflicts wherever we went, often ending in others threatening to call the police. Dad had no real friends that I knew of and, like my mother, never dated or remarried after they were together. I cut off all connection with him when I was nineteen after going to college, where I came to understand what abuse was. I didn’t speak to him again until I was thirty and a new mother myself. He was living in a flop-house in Miami, where he went in anticipation of what he thought was his impending homelessness; at least it would be warm if he had to sleep on the street was his rationale.

I didn’t know my backstory until I was an adult. Children just accept. I did know that the conventional, middle-class narrative my mother insisted on did not match anything I was experiencing or living. I was raised as the only child of a an older, single, working mother. At the same time, mom had previously been married for seventeen years and raised five children as a 1950’s housewife. Although this was in the ether of my consciousness, it was confusing emotionally. I never had the benefits of the family system I only knew of through stories, nor did I, as the sixth child, receive the spoils of an only child, which was my lived experience. My mother coped with her own shame through denial, and by shaming and punishing me for not living up to a narrative she herself was unable to live up to. Without being able to name it, that disparity presented as intense feelings of alienation. Home never felt like a safe place. To be home was to sit in rage over feeling unprotected and unheard. To be home was to be invisible and have my experience denied. The whole dynamic, however, provided me an odd amount of freedom. I didn’t fit into any defined category and had no fixed ideas about normalcy. I was a latch-key kid from a young age, alone a lot, and permitted to roam the neighborhood all day. I used that independence to seek a feeling of “home” in other places.

I lived in the San Francisco Bay Area where cultural diversity was normative and it’s where I first connected difference to liberation. I never felt comfortable with the kids and families who looked like me. I didn’t understand the unspoken rules I was always being punished for breaking, which gave me constant anxiety. I didn’t feel that pressure with my friend Sooah, first generation Korean, or with Ghada, first generation Indian/Hindu, or with Azar, American Indian, or with Courtney, daughter of the only black family in our neighborhood. For decidedly different factors, we were all either foreigners in a foreign land or foreigners in our homeland and there was a mutual acceptance through outsider status. When you are an outsider amongst outsiders, there are no rules; there is no cultural script. I could be myself and be seen, heard, and accepted, as they were by me. These early friendships taught me there were ways to think, live, and be that were different from what I was shown at home. I was fascinated by the rituals, customs, religions, and languages of my friends’ families. As a child who felt identity-less, and with no concept of white-privilege, I was painfully envious of not only their rich cultural identities, but of what I considered to be their good fortune of having brown skin or unique physical qualities that set them apart from what I knew. Difference was a place of hope, where things could change, and I associated difference with everything good. The more different than what I knew, or what I looked like, the better it seemed.

I lost all of that when my mother moved us from the Bay Area back to rural, conservative, all white, Christian, Warren, Pennsylvania when I was ten years old. I was thrown into an instant, extended, significantly older, “family” that I never knew and couldn’t relate to, and who couldn’t relate to me, with the expectation of unquestioningly falling in line. I was out of place and alone but simultaneously desperate to find connection and have a sense of family, even if it meant conforming to uncomfortable standards. That manifested itself by me 1) becoming a cheerleader and 2) being baptized into the Roman Catholic church, both at age twelve.

I had only been to church a few times before coming to Pennsylvania. Religion was otherwise never a part of my daily life. In Pennsylvania, however, everything involved church. Everyone talked about church. Everyone went to church. Everyone was in a church-group. If you weren’t part of a church, you didn’t exist. And here I was, this no middle-name having, transplant outsider from California who wasn’t even baptized. Church was the answer to my problems in my twelve-year-old mind, along with cheerleading. These were two things that seemed to give people instant social acceptability. I would walk to Sister Musante’s apartment in my cheerleading uniform every Wednesday after school in seventh grade where I would study the bible with her, pretending like I understood what she was talking about, and/or cared; neither of which I did. I just wanted to belong. I was baptized along with several converting adults on Easter Sunday that year. It never did change my life or solve my problems, but the dominance of the social structure I lived in had been so powerful against my vulnerability at that age, I felt the only way I could survive was to conform. I ultimately rejected the church a few years later. By that point, I was also rebelling against forced oppression in many other ways, often self-destructive and dangerous. [My saving grace was memory, and stories. I consumed memoirs and in absence of diversity around me, I found connection through stories that gave voice to my own.]

[I left home for college at seventeen and went back to seeking that connection within diversity which had always given me solace. I found it in the art world and the queer community. I found it in political protest. I found it in traveling, in living abroad, and living in cities and neighborhoods where I was the minority, the outsider, but this time by choice. I sought out places where I didn’t have to live by social norms that didn’t make sense to me. I sought out the places where I felt free, where I felt seen, heard, and accepted, and where I could hear and give voice to other’s stories in a way I wasn’t able to for myself as a child.]

[It’s painful to feel disconnected, or that you have no existing identity to attach to. At the same time, with a blank slate you can invent the world you want to live in and aren’t bound to any preconceived structures of how to exist.]

References

Chen, Y. (2016). “What’s in a name?” Shifting meanings, negotiating identities, and globalizing relationships . In Our voices Essays in culture, ethnicity, and communication (6th ed. (pp. 19-24). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.