By Jake-ann Jones

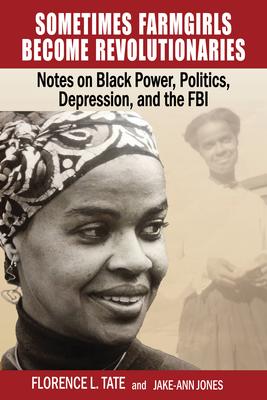

Sometimes Farmgirls Become

Revolutionaries: Notes on Black

Power, Politics, Depression, and the FBI

a new book by Florence L. Tate and Jake-ann Jones

. . .

Author Talk February 22 at 7 pm

Tombolo Books

Details here

. . .

About the Book

Florence Louis Grinner Tate kept a vast collection of press releases, articles, letters to the editor, communications from politicians and organizational leaders, flyers, essays and other writings in a dozen or more boxes in her Sarasota garage. The journal from which much of this book is taken was kept in the study she shared with her husband Chares. Her FBI files, now bound with a photo of Stokely Carmichael on the cover, was kept on an end table in the living room.

Between 2010 and 2013, Florence and I sat, walked and on occasion – on the way to a movie or a health visit – drove with a tape recorder perched between us in the ‘on’ position, recovering what seemed like hundreds of hours filled with memories of her past.

Sometimes she clearly enjoyed the process of sharing stream-of-consciousness recollections of her 80+ years – other days she dutifully strained to chip away, unearthing less-savory memories. Sometimes dates were foggy – she ruefully reminded me about her memory loss, much of it from age, some from electroconvulsive treatments. Towards the end, she would glower at me in near resentment as I asked her to once again, cover old ground we needed ‘more of.’

Sometimes she refused to talk about the past at all, and instead insisted we tune into Facebook to see who was up to where and when, or call her sister Lucille or oldest friend Josephine to help recall, or correct a memory. Still other times she would chuckle in glee as she strained to speak over a three-way call with Miriam and Dick Meisler, Paul Delaney, Laverne McCain or another old friend, while they prodded each other’s memory to get to the ‘fact’ of the event – or their closest shared approximation of it.

When she talked about the memoir’s publication, it was often with a wistful sigh, “If I’m still alive to see it.” Of course, I poo-poohed her and changed the conversation to an upbeat discussion of what fantastic outfit she’d wear to the book party, which of course would be planned by Mae and Kay Shaw, who really knew how to “throw a party.” She’d stare at me sternly. “Ok, now, Jake, you have to promise to get this book out when I’m gone.” I would return a baleful gaze and shush her “negative” vibes, wanting to hear none of it.

In the end, of course, that’s what this is. Me, trying to fulfill a promise.

This book was sewn together in a manner that can best be described as an incomplete collage of Florence Louise Grinner Tate’s life on the planet. There was a lot to choose from – but, even with all that we had, a lot that was undocumented – and therefore is missing.

Florence insisted that it was her farm years, her earliest memories, that made her who she was. She balked at calling the book, The FBI’s Most Wanted Press Secretary – my name for her, and one that I and others found “catchy.”

“But that’s just a small part of who I am, who I was,” she protested. “I don’t want folks thinking that part of my life was important to me!” Charles agreed. “It needs to call her a revolutionary, because THAT’S what she was,” he’d bark at me.

In the end, again, they won out. I retitled the book to honor the only title idea Florence could share. “I don’t know. Something about Eads to Angola. My life going from the farm to the Movement. Or something,” she sighed, rolling her eyes, already done with the conversation.

Sometimes Farmgirls Become Revolutionaries… It was a whisper in my ear that evoked the vastness of Mrs. Tate’s experiences and the unlikely likelihood of her journey from rural Eads, Tennessee, to the field camps in Huambo, Angola.

Mrs. Tate passed in 2014, and some of the people interviewed were interviewed after she left us. Her husband Charles passed four years later, in 2018. I wish they were both here to see that I honored my promise.

. . .

********

. . .

An excerpt from Farmgirls Become Revolutionaries: Notes on Black Power, Politics, Depression, and the FBI – by Florence L. Tate

and Jake-ann Jones

. . .

Acrid fumes and the sound of gunfire.

It is 1976 in Southern Angola, and I’m pressed against the doorframe of a shanty on the edge of a field; twenty or so yards away, soldiers slide along the ground on their bellies as bullets fly above their heads. It’s a deadly training exercise and it’s terrifying to watch.

My interpreter speaks over the barrage of gunfire in broken English, translating for the young Portuguese-speaking woman beside her – who in turn, interprets for the Lingala and the Umbundu-speaking women with us. “This is how they must train; they must be prepared. If they cannot dodge the bullets… they die.”

Soon the girls, members of LIMA, the League of Angolan Women, lead me away. We pass wire-and-wood pens holding chickens and a few goats, then travel through planted rows of maize, beans, and sweet potatoes. As we settle down in a field just beyond the farm, the musical voices of the women momentarily transport me to my own childhood in rural Tennessee…

As we trade halting scraps of conversation above the now-distant shellfire, gesturing in our patched-together language, I’m entranced by the rich, easy laughter of my young guides, and taken by their easy, unadorned beauty. I wonder if they are as jarred by the complexity of their lives as I am; the grim reality of their country’s civil war clashes with the pastoral beauty around us.

In the warm haze of Huambo’s afternoon heat, various memories of moments I’d experienced along the way to becoming an ardent Pan Africanist and well-known activist shift in and out of my mind. Yet, at this moment, I am mostly still awe-struck by my present surroundings.

How had I ended up here… surrounded by these gentle and brave young sisters fighting for their country? Some of them were as young as I had been when I’d left the south–a young, single mother… barely more than eighteen at the time.

How and why on earth had Florence Louise Grinner Tate traveled all the way from Eads to Angola?

In the echoes of those sisters’ voices, something whispers:

Because…sometimes, farmgirls become revolutionaries.

This is how it happened.

. . .

***********

. . .

Chapter 1: Seeds

From the FBI FILES OF FLORENCE TATE:

SAC, Cincinnati [sic] (167 – 1293) January 14, 1969

Director, FBI

FLORENCE LOUISE TATE

RACIAL MATTERS – BLACK NATIONALIST

Florence Louise Tate, a 38-year-old Negro female who resides with her husband in Dayton, is a representative of the black extremist SNCC in Dayton and a close friend of Stokely Carmichael.

She is included on the Agitator Index.

. . .

**********

. . .

A Sunday morning in Dayton, 1965. Outside my bedroom window there are signs that my neighborhood is on the move: Black church-going families dressed in their most respectable attire (hats, gloves, jackets, ties), on their way to ask God for another week of fortitude, self-restraint, and a roof overhead.

This morning my family is headed to church as well. It’s not going to be just another day of listening to the sermon and smiling politely at the other—mostly-white—members of the Unitarian church we joined, more for its politics than anything else.

“Florence… you coming?” Charles calls from downstairs. I can hear him trying to hustle our sons, Brian and Greg, out of the house and into the car.

“Hold on!” Quickly patting my short natural into a soft halo, adding a dab of lipstick, and clipping on my favorite pair of earrings, I can’t deny my excitement. After hurrying to the car to help settle the boys in the back and sliding in next to Charles, one look told me that beneath his calm exterior, his anticipation matched my own.

Only a night or so before, Rev. Harold J. LeVesconte – the progressive, pro-integration pastor at First Unitarian Church, had called to ask “a favor” of our family. “Mrs. Tate, perhaps you know that Stokely Carmichael is currently on a speaking tour, and we’ve invited him to come here to Dayton. He’ll be here at the church this Sunday, along with one of his colleagues, and they need overnight accommodations.” Rev. LeVesconte might have paused momentarily, but I’m sure he already knew my answer. “Mr. Carmichael has specifically requested to stay with a Negro family,” he continued. “I was wondering, could you all accommodate him during his visit?”

Charles and I were two of a handful of Blacks attending the church, and LeVesconte and many of the white members who had supported his efforts at integration were aware that we were heavily involved in Civil Rights Movement activities in Dayton and beyond. In fact, the organization we helped form, the Dayton Alliance for Racial Equality (DARE), greatly admired the work that Stokely and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) were doing in the South. Stokely, SNCC’s chairman, was encouraging a new philosophy — Black Power.

It also made sense that Stokely would want to spend as much time as possible with the Black folks who lived in the communities he was visiting; and it couldn’t be any more divinely designed, as far as I was concerned.

LeVesconte didn’t need to ask twice. “Well, of course we’d be glad to have him, and he can stay as long as he likes,” I replied, delighted at the prospect of getting to know this new leader of the Black youth movement that was shaking up the country.

Stokely’s name was already well known to many Blacks and whites across the nation, and I expected the church to be full that Sunday morning. Unitarians were known for being open-minded and more socially conscious than many other denominations. But how would they react to this young, radical firebrand?

My curiosity was also piqued because it was apparent that the Movement was branching off into two very different paths, and SNCC’s less “polite” strategy continued to make more and more sense to me. “I can’t wait to hear more about this Black Power stuff,” I assert, as the car pulls closer to the church.

Charles nodded. “Sure seems we’ve gotten as far as we’re going to, doing it the way we have been,” he sighs, speaking of integration and the current non-violent direct-action movements. We both feared that we had come to the end of what could be accomplished by pushing for integration and were fully ready to hear a more self-reliant and self-assertive message.

As we entered the church, I’m convinced that Stokely would share his cry for Black Power. Chuckling to myself, I anticipate that his vigorous proclamation of SNCC’s new direction would fill much of the congregation with dread.

It was hard to sit through the opening rituals. I tried not to be conspicuous as I searched for Stokely among the pews—pews filled with liberal, highly-educated, and largely integrationist whites.

Rev. LeVesconte finally finished his opening notes. When he introduced Stokely, the whole atmosphere of the church seemed to change as the tall, caramel-complexioned young man strode to the pulpit, extremely collegiate and attractive in a suit and tie.

I’m immediately struck by his appearance. His head is clean-shaven, and is not a style that many men sport, unless they lose their hair from old age or sickness. Later, I learned that Stokely had earlier been jailed in Alabama, where his head was shaved supposedly as a precaution against head lice.

Before he began, he looked over his audience, his eyes piercing. It might have been my imagination, but many of the white folks looked apprehensive. The silence in the church was heavy. But as his clear, strong voice reached us, his first words are a surprise.

“’There is but little virtue in the action of masses of men. When the majority shall at length vote for the abolition of slavery, it will be because they are indifferent to slavery, or because there is but little slavery left to be abolished by their vote. They will then be the only slaves. Only his vote can hasten the abolition of slavery who asserts his own freedom by his vote.’”

He pauses deliberately, allowing the impact of his words to resonate. “That,” Stokely continued, “is taken from Henry David Thoreau’s “Civil Disobedience”… written over a century ago, after his arrest and jailing for his refusal to support the system of slavery and warmongering being carried out by the leaders of the United States government. I am here today, to consider the revolutionary merits of civil disobedience, as theorized by that great abolitionist from New England, in light of the very real fight for freedom being waged in our country at this very hour.”

I found myself completely mesmerized as Stokely proceeds to eloquently compare Thoreau’s treatise on civil disobedience with the nonviolent protests of King and Gandhi — even managing to tie in a quote or two from Ralph Waldo Emerson. This was a potent touch, as Emerson has always been considered by the Unitarians the most “revered figure in the Unitarian movement.” Throughout Stokely’s speech, we could hear the white folks around us murmuring to one another under their breath, clearly stunned by this erudite young man.

Surprised by his choice of topic, I found it amusing to surreptitiously take in the apparent confusion on the faces of the white folks. Was I imagining their collective sigh of relief? After all, liberal or not, they most likely expected him to appear breathing flames—and he most certainly was not.

As he ended his remarks by encouraging each of us to do our part in striving for the lofty goals set forth by Thoreau, he was met by rousing applause. By the end, he gained far more support than he would have with an incendiary speech. My thoughts about his success were confirmed when the offering plate is passed. It seemed to me the white folks are more generous than usual – although they were fully aware that their contributions would support the work of SNCC and its new focus on Black Power – which Stokely had cleverly held as the final focus of his sermon.

. . .

************

. . .

This was classic Stokely, as I was to learn. With a tactical brilliance, he always carefully considered how best to connect with his audience, never underestimating the power of his words, or his ability to impact his listeners deeply.

Years after that first meeting, I received the voluminous FBI file filled with references to, and accusations about, my dealings with Stokely and SNCC, DARE, and my associations with the many other community and political organizations I worked for. I felt it to be a testament to my decades of work in the Civil Rights Movement throughout the Midwest, and alongside proponents of the Black Power Movement. The file was also a reminder of my experiences with Pan African and African Liberation activities both abroad and in the U.S.

These very same activities ultimately resulted in my coming under the scrutiny of the U.S. government, and caused me to be branded as a “rabble-rouser,” and “agitator.” I’d been linked to organizations and people labeled as “seditious,” and a “threat to internal security”—all terms used in the FBI’s Counterintelligence Program (COINTELPRO). These terms were repeatedly used to describe me and my activities in the FBI file compiled over a number of years.

To me, the file also symbolized the many years I spent in partisan politics, including my time as press secretary in the early part of Jesse Jackson’s historic 1984 Presidential campaign, and the excitement and coalition-building I experienced working alongside D.C.’s Mayor, Marion Barry, during both his initial run and his first year in office.

Although one friend joked while perusing its pages: “We need to call you, The FBI’s Most Wanted Press Secretary!” – the FBI file only told part of the story. And not even the truth of the story, most of the time.

I prefer to think of its contents as reminders of the roads I’ve traveled from Eads to Angola – from my life as a farm girl to my life as a freedom fighter; or, in my husband Charles’ lexicon, a revolutionary.

. . .

**********

. . .

After receiving my FBI files, and sifting through the copied pages of classified memos, newspaper articles, and case reports, I gradually realized how closely my comings and goings had been monitored. I was astounded by the depth of detail captured to track the minutia of my life, a project on which the government had seen fit to waste taxpayers’ dollars. It was shocking to read how low they would go to bring discord into my personal life for the sake of halting my political work.

Although I had not been politically active for a while and considered myself to be retired, reading the file caused me to wonder just how much privacy there was in “retired” life. Would the FBI ever stop watching me after almost two decades of surveillance? The last pages of the dossier seemed to recommend that my file be closed, as I was mainly considered a “housewife” in D.C. at that point. But the file made me wonder how long they watched my comings and goings… and listened in on my conversations. Had my phone been tapped all that time?

I recalled an incident that occurred two decades earlier. Charles and I were working with DARE and were on our way to a “get out the vote” event in Cleveland. I called Mother, grateful that she was around to help since her recent relocation to Dayton. Although my mother wasn’t big on the Civil Rights Movement, she’d come to realize how important the Movement was to me. We’d been estranged for many years, so after decades of struggling with difficult emotions toward her, relying on her as a support had become a very different, but welcome, experience.

After a bit of small talk, I brought up the weekend. “Well, Mother, I was wondering… could you keep the kids while Charles and I run up to Cleveland this Saturday? We’ll be back by Sunday night, not too late.”

Like most Black activists of the time, we had to work during the week — but our evenings and weekends could quickly become filled with various meetings, picketing, and leafleting. As the years went by, when more activism was required, I became more and more reliant on my oldest child, Geri, to take care of her brothers after school or on weeknights, and on Mother for the weekends.

“I’m sure I can, but I’ll let you know later this evening,” Mother assured me.

Suddenly something on the line distracted me. I pressed my ear into the headset, listening intently. “Wait – do you hear that?” I paused, straining to identify the hollow crackling that had begun to distort our telephone connection. “I hear something strange.”

Before Mother could reply, I loudly announced into the odd, familiar echoing, “Whoever that is—can you please hang up? I just want to talk to my mother!”

Silence. A few seconds later, there was a strange series of clicks.

Mother sighed. “Louise,”— the name my mother and all my other relatives have called me since childhood — “what is going on?”

I ignored her question, not wanting to remain on the line any longer than necessary. “It’s OK, Mother. Just call me back when you know for sure about the weekend.”

Hanging up, I thought, they’re getting mighty bold. What next?

This wasn’t the first time I had heard telltale sounds indicating a wiretap on my phone, nor would it be the last. More than anything, it was a reminder that even my most private communications were at risk of being intercepted and exposed.

Reading the file was also a chilling reminder that those doing the intercepting were powerful enough and had the means and the authority to keep me on their radar all these years.

. . .

Sometimes Farmgirls Become Revolutionaries

is available at Tombolo Books here and through Black Classic Press here.

. . .