August 7, 2020 | By Margo Hammond

. . .

On walks through my neighborhood in south St. Petersburg — a daily ritual I have adopted during this time of coronavirus lockdown — I have been looking more intently at my neighbors. No, not the human ones, but the things of nature whose ancestors were here way before ours.

Those things with feathers, for example. Is that an egret, a heron or a pelican? Was that an osprey diving into Tampa Bay? Did I just see a mockingbird attacking a black bird? Is that a woodpecker I hear?

Or the oaks, pines, magnolia and palm trees which, according to environmental scientists, actually form communities and communicate with each other. What messages are they sending to each other? I wonder as I pass by.

When I’m not outside contemplating nature, I find myself inside reading more and more nature books. Three recently published ones offer a window on Florida’s natural world – I Have Been Assigned The Single Bird: A Daughter’s Memoir by Susan Cerulean; Cat Tale: The Wild, Weird Battle to Save the Florida Panther by Craig Pittman and Voices of Booker Creek, a collection of writings inspired by a nature writing class offered by USFSP professor Thomas Hallock. The Booker Creek book addresses the intersection of race and nature in St. Petersburg, offering stories about a forgotten waterway and the community on its banks that was also left behind.

This month’s pick for the Museum of Fine Arts Virtual Book Club also addresses the intersection of race and nature. The group’s discussion of Remembering Paradise Park: Tourism and Segregation at Silver Springs is scheduled for August 13 from 6:30-7:30 p.m. Access to the online discussion is free but limited to 50 participants – registration is required.

And, finally, I recently ordered a copy of Mary Ann Carroll: First Lady of the Highwaymen from the St. Petersburg Library system (which has begun to distribute books again on a limited basis at its main and Mirror Lake branches, with curbside pickup) to remind myself that nature is there for all of us to seek some solace in this time of loss and disorientation.

. . .

I HAVE BEEN ASSIGNED THE SINGLE BIRD: A Daughter’s Memoir

by Susan Cerulean

University of Georgia Press, 2020

“I Have Been Assigned The Single Bird offers a lament for the precious things that have passed, an elegy for the fragile beauty that remains, and a recognition of the inseparable Nature of all living things,” writes naturalist, wildlife artist and nature writer Joe Hutto.

Its Tallahassee author — a self-described writer, naturalist and earth advocate — has written many books on nature: Tracking Desire: A Journey after Swallow-tailed Kites, UnspOILed: Writers Speak for Florida’s Coast (co-edited with Janisse Ray and A. James Wohlpart) and Coming to Pass: Florida’s Coastal Islands in a Gulf of Change.

But I Have Been Assigned The Single Bird, a memoir, is her most personal to date. It juxtaposes her role as a caretaker for her father who has dementia and her volunteer work protecting wild shorebirds along the Florida coast on a tiny island just south of the Apalachicola bridge.

This month you can hear Cerulean talk about the book at Zoom sessions sponsored by Tallahassee’s Midtown Reader at 6 p.m. on August 7 (with FSU professor and former St. Petersburg Times writer Diane Roberts) and by St. Petersburg’s Tombolo Books at 6:30 on August 19 (with USFSP professor Tom Hallock).

You can register for the Tombolo event here and a Zoom link will be sent to you closer to the event date. You can pre-order a signed copy of the book here.

. . .

CAT TALE: THE WILD, WEIRD BATTLE TO SAVE THE FLORIDA PANTHER

by Craig Pittman

Hanover Square Press, 2020

Craig Pittman, the author of Oh, Florida!: How America’s Weirdest State Influences the Rest of the Country, tells another weird Florida story in Cat Tale, describing with his trademark mixture of humor and erudition how a motley crew of people sought to save the Florida panther from extinction.

Among the panther’s would-be saviors were a grizzled old Texas trapper, a rich scientist, a retired showman, a biochemist who looked like Santa Claus, two former Detroit bootleggers, a veterinarian who collected panther semen and a biologist known as “Dr. Panther” who nearly derailed the effort with faulty research.

It took Pittman more than a decade to finish Cat Tale, which was published in January. Why so long? He compiled much of the research for the book while he worked as an environmental writer for the St. Petersburg Times (now the Tampa Bay Times), but he was waiting for a happy ending to the story, he told CBS Miami in February.

Despite all the bungling and professional rivalries, those seeking to pull the panther from the brink of extinction finally largely succeeded.

In the ‘70s, there were about 20 in the state. Today the population of panthers, long thought to be spiritual beings by Native Americans, numbers about 200. Pittman’s CBS Miami interview gives us a glimpse of the graceful (and elusive) cat — Florida’s official animal — and an update on the fight to preserve the panther’s habitats, still threatened by interstate highways.

. . .

VOICES OF BOOKER CREEK

edited by Anna Maria Lineberger, Dylan Furness and Kelly Kennedy

University of South Florida, 2020

Voices of Booker Creek, a collection of essays, poems, interviews, news articles and even a play, is also about a fight for survival — for an almost forgotten waterway and the African-American community that has lived along its banks for decades.

The creek runs through south St. Petersburg for about three miles, from the west side of I-275 to the southern edge of the USF St. Petersburg campus, at spots along its route looking like nothing but a drainage ditch (its nickname, ‘Booger Creek,’ says it all).

In the 1920s, the waterway, which flowed through Campbell Park and the Gas Plant neighborhood, was thriving — as were the racially segregated communities that formed along its banks. But both were equally neglected.

As the city grew, at times developers built right on top of the waterway (in the construction of Tropicana Field, plowing down African American houses and churches that stood in its way). Part of the creek actually flows under Central Avenue. It then continues around Tropicana Field, beneath I-175 and through Campbell Park and Roser Park, before ending up in Bayboro Harbor.

“Booker Creek tells the story of a city that found progress at the expense of nature and a vibrant, tight-knit community,” writes St. Petersburg City Council representative Gina Driscoll in the book’s foreword. Driscoll represents District 6, which includes part of Booker Creek. “Now, after many years of neglect, there is a growing interest in stronger stewardship of the creek to revitalize and celebrate this beautiful, damaged thread.”

The voices heralding that “beautiful, damaged thread” in Voices of Booker Creek are refreshingly diverse. Joe, a homeless man, writes a poem. Shadin Haitham, one of eight Gibbs High School students whose work is included, offers a play called Fighting for Larryisha (who is a frog). County Commissioner Kenneth Welch, local historian Gwendolyn Reese, Bayfront Hospital’s first African American chief of staff the late Dr. Paul McRae and writing coach Roy Peter Clark as well as journalists, graduate students who took Hallock’s nature writing course and other lovers of Booker Creek all provide new perspectives on the waterway.

On the Voices of Booker Creek YouTube page, you can listen to the actual voices of some of the contributors as they read their stories. . . “Jesus Up the Creek” by writer Jon Wilson, “Paddling Toward Reparations” by Professor Hallock, “Ghost Houses” by USFSP professor Julie Buckner Armstrong and “Night” by Luke Bilsborough, a recent graduate of Pinellas County Schools.

“Voices of Booker Creek is a testament to St. Petersburg’s black communities,” says Anna Maria Lineberger, a professor of composition at St. Leo University, who edited the volume along with Dylan Furness and Kelly Kennedy. “It serves as one piece of a vast story stretching before and beyond itself. It bears witness to something far greater than what we can contain in one volume.”

. . .

REMEMBERING PARADISE PARK: TOURISM AND SEGREGATION AT SILVER SPRINGS

by Lu Vickers and Cynthia Wilson-Graham

University Press of Florida, 2015

Race and nature are also addressed in Remembering Paradise Park: Tourism and Segregation at Silver Springs, the MFA Virtual Book Club’s pick this month.

During the era of Jim Crow in Florida, even nature was segregated. Then, the state’s famed tourist parks were off limits to Blacks — with one exception. Silver Springs, the park known for its glass-bottom boat rides down the Silver River, offered a parallel facility for “colored only” called Paradise Park.

Operating for 20 years, the segregated counterpart to Silver Springs provided one of only three beaches that were opened to African Americans in the state at that time. Lu Vickers and Cynthia Wilson-Graham chronicle the story of this leisure spot where Black and white families shared the same river but rarely crossed paths.

Blacks were admitted to Silver Springs in 1967. Paradise Park was officially closed in 1969.

. . .

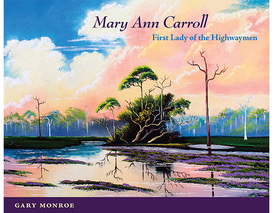

MARY ANN CARROLL:

FIRST LADY OF THE HIGHWAYMEN

by Gary Monroe

University Press of Florida, 2014

Of course, the state couldn’t segregate all of nature — as one book I recently ordered from the library reminds me – Mary Ann Carroll: First Lady of the Highwaymen.

In the 1960s and 1970s Carroll was part of a band of African Americans painters who traveled around the state to capture Florida’s natural beauty on canvas and then sold their landscapes door-to-door and by the roadside.

Carroll was the only female and her story tended to get lost in all the later paeans to the Highwaymen, as the moniker to these painters belies.

But in 2012 she was recognized, along with James Gibson, by First Lady Michelle Obama for her talents at the Florida House in Washington D.C. and in 2014, the University Press of Florida published a book dedicated to her work.

Filled with Carroll’s vivid landscapes, the story told by Gary Monroe is of a Black female artist’s hard-fought journey to provide for her family (she raised seven children) while making a name for herself in a man’s world.

“Life is not about being a male or a female,” she told Monroe, “It’s about surviving.” Carroll died in December at age 79.