Honoring the Beat Prophet in his Adopted Hometown

“‘A prophet is not without honor

except in his hometown.” – Matthew 13:57

There’s a Jack Kerouac Park in Lowell, Massachusetts where the author was born, a Jack Kerouac Alley in San Francisco where he was launched as a poet and Beat writer, a rue de Jack Kérouac in Quebec City in honor of his French Canadian ancestry, a rue Jack Kerouac in the hamlet of Kerouac in the French region of Brittany which is the source of Jack’s surname and a Jack Kerouac sign in front of the house where he lived in Orlando. There’s even a crater on Mercury named in honor of Jack Kerouac.

So why is there no monument, no park, no street named after Kerouac in St. Petersburg — not even a plaque at St. Anthony’s Hospital where the iconic author died on October 21, 1969?

I was puzzled by this when I arrived here in 1990 to work as book editor at the St. Petersburg Times. Wasn’t Kerouac considered an important enough literary figure to honor? Was the town embarrassed that St. Pete had become the end of the road for the troubled author of On the Road?

When I proposed to include a Kerouac tribute at the first Times Festival of Reading in 1993, I was met with skepticism. My colleagues at the Times questioned Kerouac’s literary merit (“You know what Truman Capote says about Kerouac’s work: ‘That’s not writing, that’s typing’”). Some felt he was a poor role model (“You know, he drank himself to death here”) as if suffering from alcoholism exempted him from posterity.

I did manage to include Kerouac panels of biographers, editors and friends who had known Kerouac in St. Petersburg at the first two festivals, but got no support to make Kerouac an ongoing feature at the festival.

Happily, interest in the Beat author has grown since that time. In 2013 Keep St. Pete Lit held its first event – a city-wide reading of On the Road. That same year The Friends of the Jack Kerouac House, Inc. was formed. Interested in turning the house where Jack had lived into a writer’s retreat or museum, the nonprofit group sponsored concerts and bike tours of Kerouac sites to raise money to buy it.

In 2016 the Dalí Museum held a celebration of Kerouac and his local legacy which included a reading from Desolation Angels where Kerouac describes meeting Salvador Dalí at The Russian Tea Room in New York: “I looked into his eyes, and he looked into my eyes, we couldn’t stand all that sadness.”

In 2017 Jack finally returned to the Times Festival of Reading – Kristy Andersen, an independent St. Petersburg filmmaker, presented Snowbird, her documentary-in-progress about Kerouac’s years in St. Pete.

And last year The Friends of the Jack Kerouac House launched the first annual Spirit of Kerouac Festival which included a Literary Roast of Jack Kerouac organized by Wordier Than Thou at The Studio@620, complete with a Jack Kerouac look-alike contest and an “appearance” of Jack himself.

This year’s festival, which features events throughout October (see sidebar), will be held virtually, of course.

One of the participants I invited to those earlier Kerouac panels at the Times festival was Ron Lowe who told great first-hand stories about Jack’s life here. Twenty years younger than Kerouac, Ron was the last in a long series of male buddies Kerouac cultivated for lively conversation — and rides home (ironically, the author of On the Road never learned to drive).

Ron had met Jack in 1965 at a St. Pete bar where Ron’s band, The Dominoes, was playing. (The band was the first racially-mixed band to play in front of an integrated audience on the beaches here, at the Peppermint Lounge in Madeira Beach).

Jack would come to hear The Dominoes and then Ron and his “philosophical talking-all-night buddy,” his “impromptu ‘let’s-drive-to- Miami-right-now’ buddy” would sit and talk up on the rooftop of the Twilight Lounge on Central Avenue or over breakfast in an all-night diner (yes, once driving a Coupe de Ville all the way to Miami).

Ron, who sadly died in 2001 before finishing his memoirs about his friendship with Jack, talked to me often about how steamed he was that biographers described his friend in his final years as washed-up and defeated.

“Those biographers who assumed that Jack crawled off to St. Petersburg to die didn’t have to try to keep up with him,” he said. “Sure, Jack was frustrated (‘I live in a monastery with my mother’) and, yes, he drank a lot (‘Any freshman who’d read his Kerouac knew that’) but, he lived ’til he died.”

And continued to write.

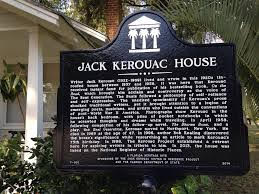

While living at 5155 10th Avenue N. with his mother from 1964 to 1966, Kerouac wrote about sports for the Evening Independent, a sister publication of the St. Petersburg Times – and most likely finished Sartori in Paris, published in 1966, in that house.

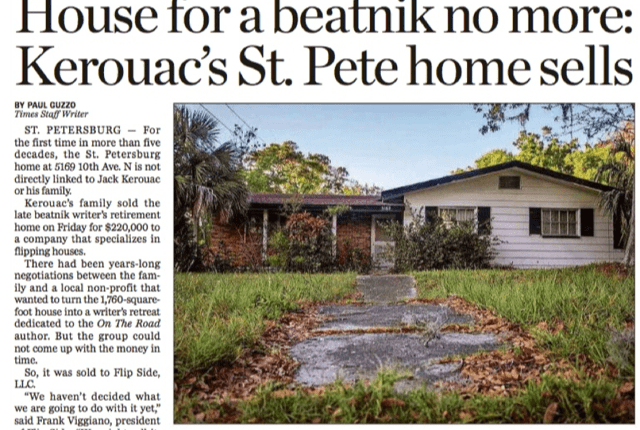

In 1966 Kerouac returned to Massachusetts, but he came back to St. Petersburg a second time in 1968, buying the house right next door at 5169 10th Ave. N. This time, along with his mother, he brought his new wife, Stella Sampas, the sister of his childhood friend in Lowell.

There is some speculation that Kerouac might have written some of Vanity of Duluoz, a semi-autobiographical novel about life between 1935 and 1946, in that second 10th Ave. N. house. His last published work, it appeared in 1968.

And those houses? Unlike the cottage where Kerouac wrote Dharma Bums in Orlando which has been turned into a writer’s retreat, neither of the Kerouac houses in St. Petersburg has been given such literary status.

Not that The Friends of the Jack Kerouac House didn’t try. John Sampas, Kerouac’s brother-in-law, who inherited the dwelling from his sister, made the nonprofit group the home’s caretakers. Volunteers went to the house to care for the lawn and to regularly empty the mailbox which routinely was stuffed with fan mail to Jack. “”Dearest Jack,’ reads one,” reported Ben Montgomery in the Tampa Bay Times. “‘Thank you for everything. Your work is why I write, and write to live.’ ‘Hey Jack, We came by to say hello,’ says another. ‘Sorry we missed you.’”

To raise funds for house repairs, the group held concerts, led by Pat Barmore and Pete Gallagher, at The Flamingo Sports Bar on 9th Avenue N. The bar, which sports a gigantic photograph of Kerouac on its facade, claims that the author hung out there to play pool and drink “a shot and a wash,” a whiskey with a plastic cup of beer that’s served now there as the Jack Kerouac Special.

According to Margaret Murray, even the city started to show interest in Jack Kerouac. She singled out Council member Amy Foster as being particularly supportive of the group’s efforts.

Murray organized the bike tours. They grew out of her graduate thesis at Savannah College of Art and Design. “They were tours of Jack Kerouac in St. Petersburg, but also of the history of the city and how it’s changed,” says Murray, now the associate curator of public programs at the Museum of Fine Arts.

Murray would add and subtract sites to the tours as she continued to research Kerouac’s time in St. Pete. Among the popular stops were the Twilight Lounge at 2235 Central Ave which in Kerouac’s time stood next to an International Harvester store selling tractors, and the site of the old holding cells at the police station where Jack was arrested for public intoxication after he went on a binge when his sister Caroline died in 1964.

Neither did much to bolster Kerouac’s artistic bona fides.

Murray, who serves as treasurer for the Kerouac nonprofit, admits there always has been that concern that Kerouac wasn’t literary enough. “But to be fair, even Jack’s friends in New York were embarrassed by how his life ended,” she points out. “We all have experienced how an alcoholic can cut off connections and lose their friends’ support.”

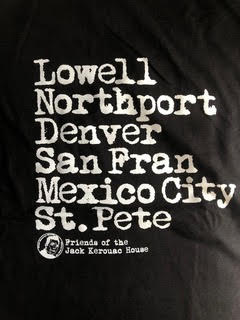

Kerouac tee, available at the Friends of Jack Kerouac House Etsy store

There was one decidedly literary stop on Murray’s tour though – Haslam’s Books.

Jack used to stop there regularly to see if his books were on the shelves and complained when they weren’t. Ron Lowe was convinced that Kerouac haunted the store after his death.

“For years now there have been strange reports coming out of the Central Avenue bookstore,” Lowe wrote in one of the many reviews of books about Jack that he wrote for the St. Petersburg Times. “Seems when the store is opened in the morning, there are sometimes books dislodged and laying on the floor. They’re always Jack’s books.”

In 2015 Sampas suddenly changed his terms with the Kerouac group, changing the house’s locks and offering to sell the place to them — for a whopping $500,000. When Sampas died in 2017 without a sale and the house passed on to his son, the battle over the fate of the Jack Kerouac house intensified — and got more complicated.

In 2019, some members who had originally founded The Friends of the Jack Kerouac House — including Barmore and Gallagher — split away to form a second group, The Jack Kerouac House of St. Petersburg, Inc, to more intensely focus on raising the money needed to meet the Sampas family’s asking price. They announced they wanted to turn the house into a writer’s retreat.

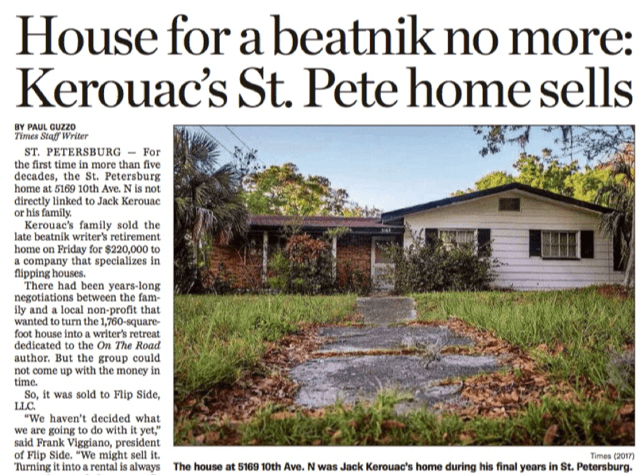

But, alas, the group was unable to raise enough before the family’s June deadline (even at the lowered asking price of $300,000), and at the end of June the house was sold for $220,000 to Flip Side, LLC, a developer, as its name implies, devoted to flipping houses.

The headline about the sale in the Tampa Bay Times — “House for a beatnik no more” — must have been particularly galling for Jack Kerouac’s ghost. “I’m not a beatnik,” Kerouac famously said. “I’m a Catholic.” A political conservative, Kerouac loathed the hippie generation he was said to have inspired. When he named the Beat Generation, he often explained, he meant “beat” as in beatific not beatnik or the beat goes on.

Kerouac was a Catholic but he also embraced Buddhism, especially during his final years. On the first page of kerouachouse.com, the website of the original Kerouac nonprofit, there is a poignant image of Jack living at the 10th Avenue N abode: “Attempting to reconcile his Buddhist leanings with his overwhelming urge to drink and carouse, he spent many nights in the peaceful backyard, dragging a cot outside to sleep under the stars.”

That original Kerouac group, which since the split has expanded its board of direction, now calls itself simply Friends of Jack Kerouac. It has refocused its mission. “For the time being, we are moving away from an emphasis on property acquisition, explains USFSP professor Thomas Hallock who is the group’s vice president, “and focusing more on Kerouac’s literary legacy. Through community discussions and arts and cultural events, we want to spark the creative spirit within us all.” Plans include mapping outdoor routes for cultural-literary tourism, readings and critical discussions, as well as outreach with the community and allied groups. And continuing the annual Spirit of Jack Kerouac Festival.

Meanwhile, the second Kerouac nonprofit hasn’t given up completely on the acquisition of Jack’s house and the dream of turning it into a writer’s retreat. “We will remain hopeful,” Barmore, the president of The Jack Kerouac House of St. Petersburg, Inc. told the Times after the June sale. “Maybe an angel will fall out of the sky.”

And maybe one day in St. Petersburg, we’ll drive down Avenue Jack Kerouac.