January 10, 2019 | By Steven Kenny

Now part of the permanent collection

Museum of Fine Arts, St. Petersburg

Details here

One of the many ways in which art functions is to help familiarize us with ideas, cultures and individuals we may otherwise not be exposed to.

One of the many ways in which art functions is to help familiarize us with ideas, cultures and individuals we may otherwise not be exposed to.

This has always been the mission of any encyclopedic art museum. St Petersburg’s Museum of Fine Arts’ recent purchase of a large Kehinde Wiley painting serves that function brilliantly — while greatly enriching its collection of contemporary art.

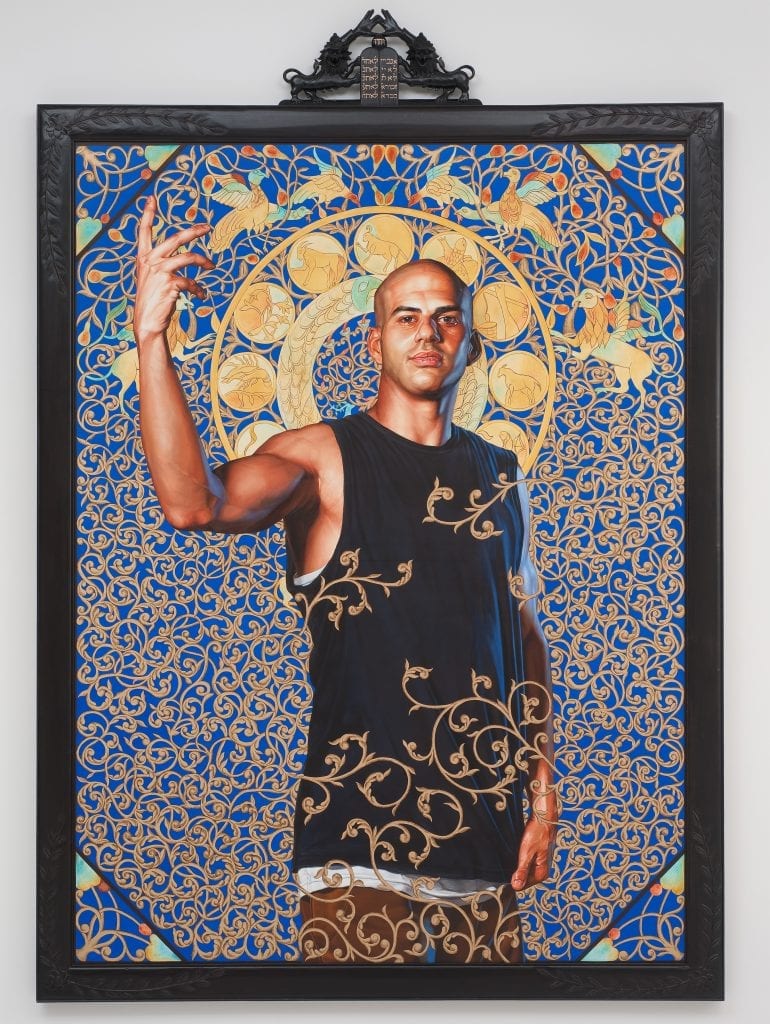

Leviathan Zodiac (The World Stage: Israel), 2011, oil and gold enamel on canvas, is an enormous portrait of a young Israeli man, casually dressed in a sleeveless shirt, standing in a pose reminiscent of the well-known statue of Augustus Caesar in the Vatican Museum. Like Caesar, Wiley’s subject holds his head up proudly with an expression of self-possession while his right arm is raised in a magisterial gesture.

Swirling behind and partially in front of him is a pulsating blue and gold pattern evoking decorative Jewish ornamentation. A halo containing images of the zodiac frames the man’s head. The black, ornate, hand-carved frame designed by the artist boldly surrounds the lush, vibrant colors that radiate from the painting. It is embellished at the top with symbols relating to the Old Testament.

There is a long tradition of painters updating classical and religious themes. Two artists who come to mind are Caravaggio and Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Both reinterpreted scenes from the Bible by dressing figures in contemporary clothing. This made the messages and stories more resonant by transporting them into the present day — allowing viewers to see themselves in the art and reminding us that these lessons continually repeat themselves. Wiley is doing the same for us.

It is common that museum visitors are exposed to works created in the near or distant past and, while able to enjoy them aesthetically, feel little or no connection to the actual subject being presented.

Wiley changes that by presenting us with ordinary young men and women he meets in his travels — people resembling those we might pass on the street every day. Here, he goes a step further and focuses on people of color who emigrated to Israel, many having “been mistreated in their home country.” Wiley imbues them with the dignity, respect and status they have previously been denied.

To create his World Stage series of paintings (of which this is one), Wiley said he traveled to countries including China, Brazil, Nigeria and Israel “to chart the presence of brown and black people throughout the world.” He frequented a wide variety of locations like markets, beaches and clubs to find his models, getting to know them individually through speaking with them and visiting their homes.

Wiley’s paintings illustrate the fact, perhaps truer today than ever, that there are undeniable threads connecting everyone on a global scale.

Perhaps Wiley’s best known painting to date is his presidential portrait of Barack Obama that now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC. Obama chose Wiley specifically for the task, knowing full well both Wiley’s great talent as a representational painter and his reputation as a champion of equality and inclusiveness. In this case, however, instead of depicting Obama in a stance reminiscent of some historic military leader, Obama sits casually in a chair, open shirt collar, hands crossed on his knees, accessible to all.

Wiley is a great artist doing important work. He’s an artistic ambassador making connections in the hope of bringing us a little closer to understanding and accepting each other. The Museum of Fine Arts, with the generous help of donors, is doing its job, too — and St Petersburg is very lucky to have Leviathan Zodiac.