June 14, 2021 | Story and Photos by Margo Hammond

. . .

Jim Sweeny has collected art for decades, but most of the pieces he’s acquired haven’t ended up over his couch — or even in his home. He prefers to share the art he finds.

Over 300 hundred pieces that he collected with his wife Martha, who died in 2019, are now part of the permanent holdings of St. Petersburg’s Museum of Fine Arts. Dozens more have been donated to the Leepa-Rattner Museum in Tarpon Springs – and the most recent donations to the Leepa-Rattner are up on the museum walls as part of an exhibit highlighting African American prints, on view through August 29.

Oh, and a glass vase created by a high school buddy and five paintings from Creative Clay that Sweeny donated to Westminster Palms, a senior assisted-living community north of St. Petersburg’s downtown where he came to live in 2017 when Martha fell ill, are on display in the complex’s Royal Palm dining room.

The Sweenys didn’t start out buying art for other people to enjoy. The first pieces the couple purchased — over 40 years ago — were for their own viewing at home.

The earliest painting — by contemporary artist Maurice Clifford — still hangs on a wall in Sweeny’s apartment at Westminster Palms.

A St. Petersburg native, a Northeast High School graduate and a 1965 graduate of Eckerd College, Sweeny bought the Clifford painting while he was working as a chemist at the Coca Cola Company in Atlanta. His wife was administrative assistant to the curator for decorative arts at Atlanta’s High Museum of Art. They had met while Martha was also working for Coca Cola (in the company’s wine division, which eventually was sold to Seagram’s). Her new position at the museum had plunged the couple into a whirlwind of art openings, kickstarting their interest in acquiring art for themselves.

“We went to everything — exhibits of pottery, photography, glass,” says Sweeny. The Sweenys were most touched, however, by the self-taught art they saw. After the Clifford purchase, they started more and more to collect pieces of what is sometimes called visionary art, sometimes folk art.

That art was affordable and often the artists were as unique as their work.

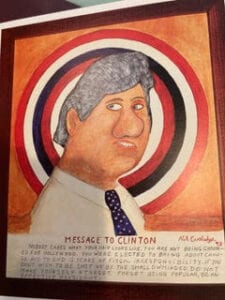

In the case of Georgia-born sculptor Ned Cartledge, they became friends with the artist. Every two weeks, says Sweeny, he and his wife would go out to dinner with Ned and his wife Amy. Cartledge, who sold lawn mowers at Sears when he wasn’t whittling his colorful wooden bas-reliefs, preferred the Longhorn Steakhouse, the Fortune Cookie Chinese Restaurant and the Red Lobster. At one of Cartledge’s exhibit, Sweeny overheard someone ask Ned, “Didn’t you sell me a lawn mower at Sears?” Sweeny sighs. “Ned talked about lawn mowers for the rest of the evening.”

Cartledge, who died in 2002, often mixed political themes and humor in his art. “When people asked him what inspired him,” says Sweeny, “He answered, ‘I’m not inspired. I’m provoked.’”

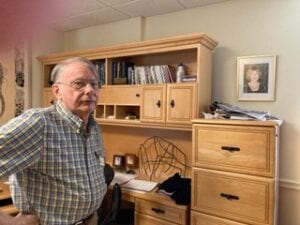

I am chatting with Sweeny in his apartment at Westminster Palms. Also with us is Sweeny’s friend Elie Visel, a 95-year-old fellow resident of Westminster who befriended the Sweenys when they arrived at the complex. Visel, Sweeny tells me, has quite an art story to tell herself. Through her brother John Rublowsky, she met Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein and other Pop artists who gathered at her brother’s Park Slope townhouse. A musician, her brother was the author of Pop Art, illustrated by Ken Heyman – the first book on the pop art movement.

Earlier the three of us had taken a tour of Westminster Palms, to see the pieces Sweeny had donated. The first — a massive glass vase infused with a scene of egrets, palm trees and a setting sun — was posed on a side table in the sprawling dining room on the first floor. The piece was made by Chuck Boux, a classmate of Sweeny at Northeast High School. Boux, Sweeny explains, started out as an electrician but while he was in New York rewiring the World Trade Center in the ‘80s, he saw an exhibit of glass art in a gallery and was inspired to start making glass art himself. In 1991 he founded the Sigma Glass Studio. His glass art is now on display at the Imagine Museum and Florida Craft Art in St. Petersburg.

The second Sweeny art donation to Westminster was located on a wall in a small dinning room beyond the main hall – five colorful paintings of palm trees by members of Creative Clay. The paintings, per the custom at Creative Clay, are only signed by the artists’ initials. Sweeny has been an important supporter of the organization which provides art experiences for people with disabilities and neuro-differences.

Up in Sweeny’s apartment, visitors are greeted at the door by a collage by Tallahassee-based Mary L. Proctor. Across the room, I spot another Proctor – a full-sized door propped against a window featuring quilt squares and a woman at a loom under the title A Time to Quilt followed by this quirky, run-on sentence, “They sat hours pulled out bags of clothes bow ties that was no longer to be worn quietly they sat and patch together a lovely quilt made out of scrap clothing for peace and love to share with others.”

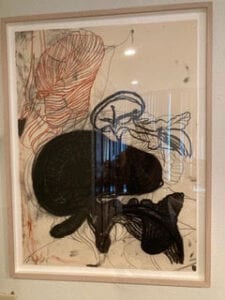

On the way to showing me more artwork in his home office, Sweeny stops and points out a print on the wall by Brooklyn abstract artist Terry Winters. He bought it at a fund-raiser for the Brooklyn Academy of Music. “A lot of people miss that it’s a portrait of Snoopy,” he says, chuckling. In his office, there’s a small Santa sculpture by Cartledge, another Winters print called Marginalia (1988) and two paintings by a 60-something Creative Clay artist known as Karen C.

There’s also a photo of Martha.

The Sweenys left Atlanta in 2001 after a massive Coca Cola layoff forced Jim into early retirement (he was only 58). By then Jim and Martha had put together an impressive art collection, many pieces bought from Judith Alexander who founded the city’s first folk art gallery in 1978.

In 2002, Sweeny, to associate with other professionals, joined The Academy of Senior Professionals at Eckerd College (ASPEC) — a “life saver,” he says — where he was active until moving to Westminster in 2017, co-chairing the organization’s science and visual art groups. In 2007 at a meeting of the art group (which he co-chaired with local artist Ann Rascoe), he met Jennifer Hardin, then the chief curator at the MFA, who told him that she was putting together an exhibit of what she called folk art. Jim told her he had some pieces that might be of interest to her.

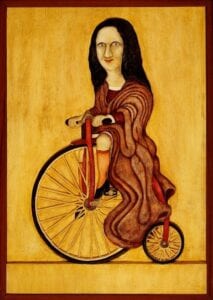

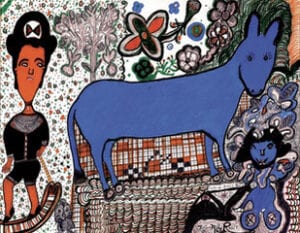

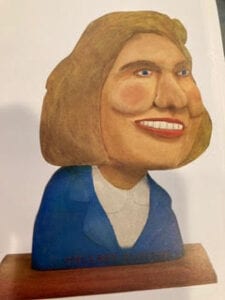

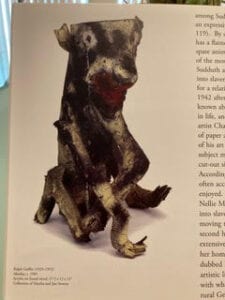

The Sweenys ended up contributing 15 pieces to the MFA exhibit called Compelling Visions, including a 1981 ink and crayon drawing on paper by Nellie Mae Rowe (who picked cotton in Georgia as a child), Owl (1947) by Bill Traylor (an Alabama painter born into slavery around 1853, who took up painting when he was 85), Monkey (1985) by Ralph Griffin (a sculptor from Georgia who had been a janitor for most of his life) and several pieces by Cartledge, including Mona Lisa on a Bicycle (1972), Message to Clinton (1993) and Hillary Clinton (1999). The exhibit ran from March 31-July 8, 2007.

After the exhibit closed, the Sweenys donated the Nellie Mae Rowe drawing to the MFA. It was their first donation, but hardly the last. The museum would eventually be the beneficiary of more than 200 pieces by self-taught artists like Rowe and other African American artists as well as another 100 prints by American women. The latter were the subject of an MFA exhibit called Marks Made: Prints by American Women Artists from the 1960s to the Present which ran from October 17, 2015 through January 24, 2016.

In 2019 the MFA again offered an exhibit featuring the Jim and Martha Art Collection, this time dedicated to the memory of Martha Sweeny who died in March of that year. Straighten Up the World: Self-Taught Art From the Collection ran from May 18 to October 27, featuring works by Howard Finster, Clementine Hunter, Mary L. Proctor, Jimmy Lee Sudduth and, of course, Ned Cartledge. In its program notes, the museum noted that the Sweenys “together had a goal of increasing representation of women artists and artists of color within arts institutions.”

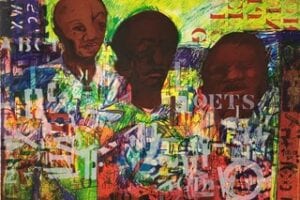

The current exhibit at the Leepa-Rattner entitled African-American Prints from the Jim and Martha Sweeny Collection continues that tradition. Showcasing Sweeny’s latest donations to the museum, again given in memory of Martha, the exhibit brings “the Black experience to the forefront through vibrant prints inspired by jazz music, quilting traditions and the African diaspora.” Prints from such influential Black printmakers as Romare Bearden and Allan L. Edmunds are on display in the exhibit which will be open through August 29.

The Sweenys’ initial donation to the Leepa-Rattner was the subject of a 2017 exhibit called Fall Into Greatness: Contemporary Prints from the Jim and Martha Sweeny Collection. That show was held in the Lothar and Mildred Uhl Works on Paper Gallery. A fellow print collector, Lothar had been a friend of the Sweenys. The 14 prints on display included works by Louisa Chase, Donald Sultan, Brad Davis, Terry Winters, Hung Liu, Howardena Pindell and Thornton Dial.

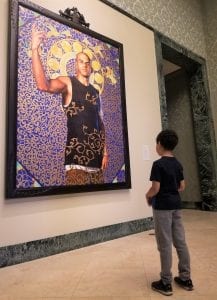

Although for the past year COVID and an eye infection (which hampers his ability to drive) have cut back on Sweeny’s participation in ASPEC, the 77-year-old’s contributions to art institutions has continued unabated. In 2020 he sponsored an exhibition of Louisa Chase’s prints at the Leepa-Rattner entitled Louisa Chase: What Lies Beneath. The display of Chase’s prints ran at the museum from January 25 to April 19. He then sponsored the exhibit Derrick Adams: Buoyant at the MFA from September 12 through November 29. He was also a major force behind the MFA’s acquisition of the mammoth 2011 Leviathan Zodiac (The World Stage: Israel) by Kehinde Wiley, best known for painting President Obama’s official portrait.

Sitting with Jim — and Elsie — surrounded by such vibrant art, I am reminded how much I enjoyed seeing Sweeny’s pieces in that 2019 exhibit at the MFA Straighten Up the World: Self-Taught Art From the Collection. I chuckled over Ned Cartledge’s wood carving depicting Diogenes, the Greek philosopher who railed against hypocrisy, in front of a mailbox labeled 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. with the caption, ”Diogenes in his search for an honest man goes to the wrong address.”

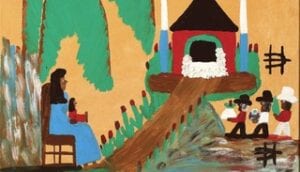

I admired Clementine Hunter’s fresh look at the scene of Jesus’ birth in her painting Nativity where the Madonna, her child and all three wise men are painted Black. I saw the exhibit a month before that fall’s presidential election and a few months before the pandemic and Black Life Matters protests after the killing of George Floyd turned the country upside down.

The exhibit’s title — “Straighten Up the World” — came from a quote by Florida artist Purvis Young, a self-taught artist who used found materials to depict scenes and portraits of people from his gritty Miami neighborhood of Overton. “I paint them all kinds of ways. . . some people protesting, some happy, some white, some are black, green or purple,” Purvis said. “People that think like me. Different kinds of people trying to straighten up the world.”

I am struck now by how well that fits Sweeny’s lifelong collecting philosophy. By sharing with all of us the art he has collected, raising our awareness of artists who have been overlooked, he too is among those trying to straighten up the world.

. . .