a Trailblazer and My Mother

. . .

From Heroes :

Stories of Sports, Courage and Class

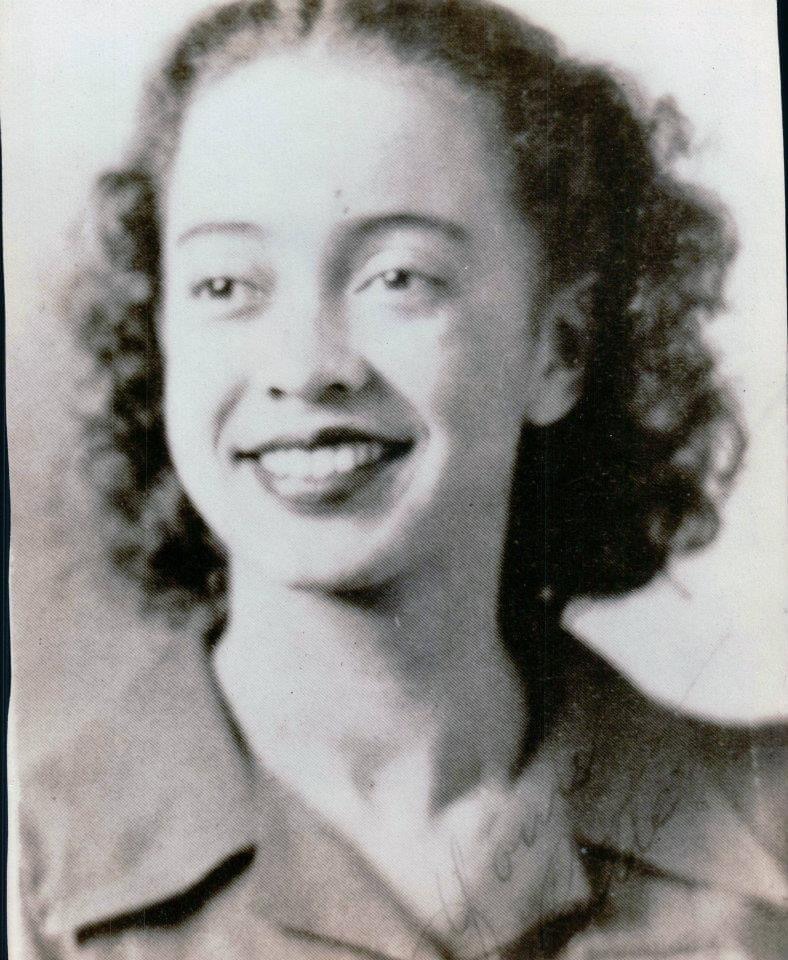

A lawyer, a politician, a trailblazer. Bette Wimbish was all that and more. She was my mother.

Mom died in 2009, but her indomitable spirit is still alive and will be with me till my dying day. Looking back, it still amazes me how well she succeeded with such grace, courage and class in such a hostile environment, in such hostile times.

The long, hard road of her prolific life had its share of potholes, twisting turns and untimely detours.

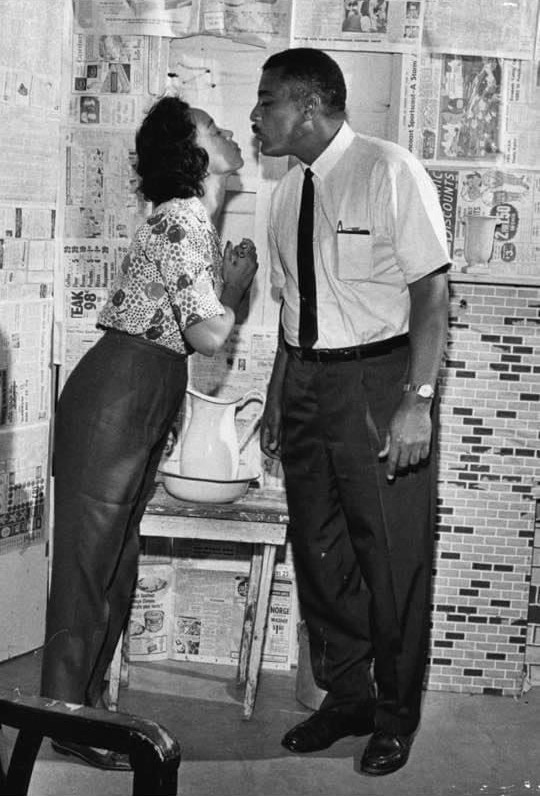

In St. Petersburg, my hometown, she and my dad, Dr. Ralph Wimbish, were right there on the front lines in the fight for civil rights. She was there in 1961 when my dad slammed Major League Baseball for spring training discrimination.

She was there when my dad sued to improve poorly funded Black schools and integrate local golf courses. She was there when he led the boycott of department stores and picketed movie theaters, restaurants and the Whites-only beaches.

In fact, my mom was always where she needed to be. Often, that was our home, preparing family meals daily and driving me and my older sister Barbara and baby brother Terry back and forth to school every day.

At nights, when she wasn’t reading me bedtime stories like The Happy Hollisters, she attended civic meetings, spoke at churches and sometimes found time to play bridge.

When it came to education, she was there pulling me and my sister out of overcrowded Black schools to integrate White ones. Barbara went to high school at St. Paul’s, I started sixth grade at St. Joseph’s. In 1964, when I became the Jackie Robinson of the Lake Maggiore Little League, she was in the bleachers, cheering me on.

Yes, the times were turbulent. In 1961, I am told a cross was burned in our front yard on 15th Avenue South. Whenever the phone rang, there was always the possibility of a death threat. At the mailbox, occasionally there was hate mail.

And there were some near-tragedies. When I was 3, I nearly drowned in a lake at a picnic in Tampa – but my mom was there to save me. A few years later, when my brother, then 2, fell into the family swimming pool, again she was there.

Otherwise, Bette Wimbish was a fearless political animal who simply never got to fulfill her ambition — to improve the quality of life for the disadvantaged, senior citizens and people of color. If you want to call that socialism, OK, she was a socialist.

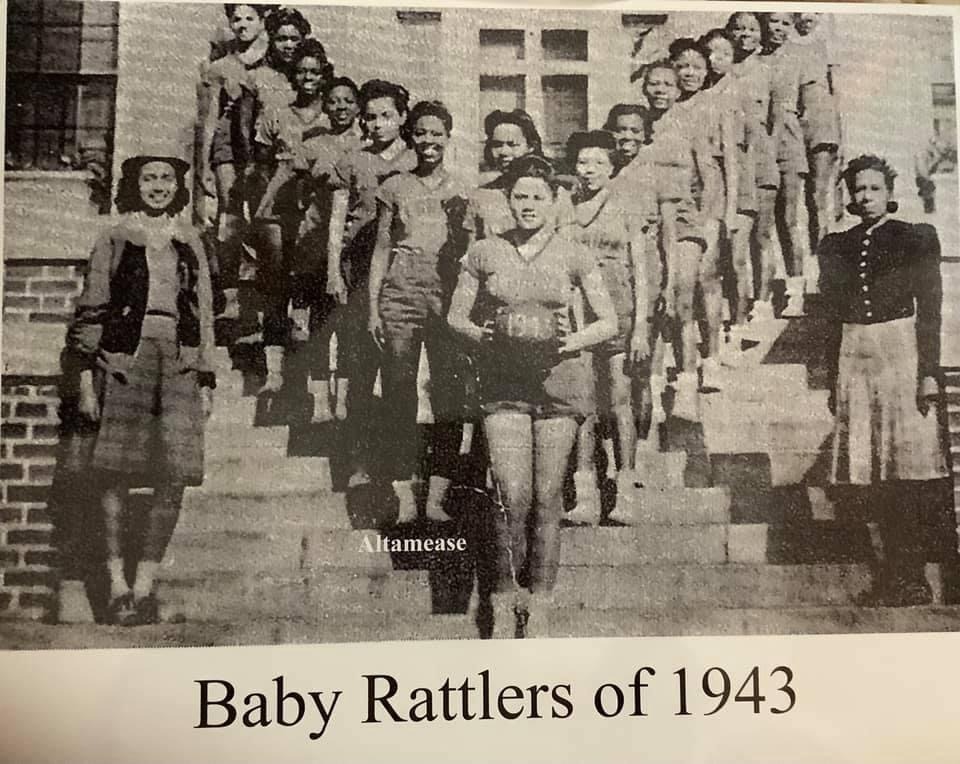

In 1960, while pregnant, she ran for the Pinellas County School Board. She lost, but her political career was just getting started. She was determined to get a law degree, so in 1965 she packed up me and my brother and we went to Tallahassee, where she completed law school at Florida A&M, her alma mater, in 2 1/2 years.

Sadly, two weeks before her final exams, my dad died of a heart attack at 45.

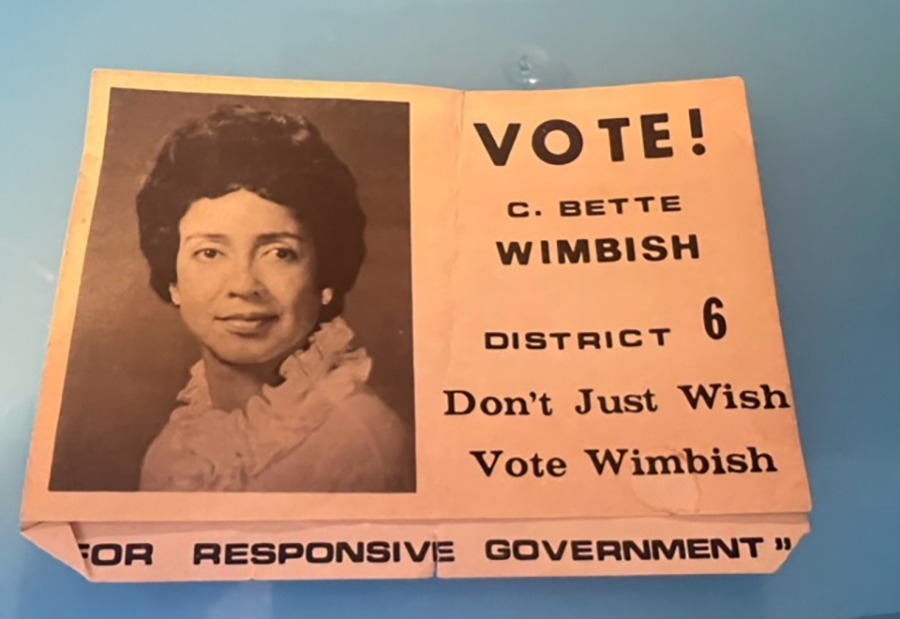

Heartbroken but determined as ever, she passed her final exams and began studying for the bar exam just as St. Petersburg became engulfed in a strike by sanitation workers. Naturally, she got involved, and though the strike didn’t succeed, it gave her a platform for a run for a seat on City Council in the spring of 1969.

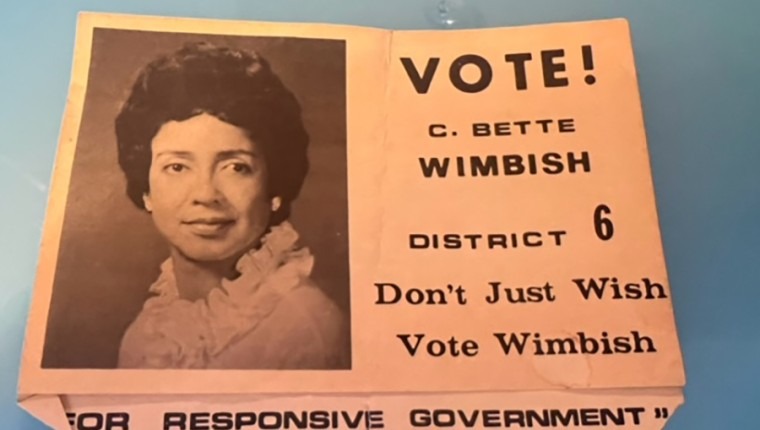

Calling for “responsive government” and equal-opportunity hiring practices for minorities, she made history, defeating the incumbent, Martin Murray, for the District 6 seat and becoming the first Black elected official in the Tampa Bay area.

City Council was a real challenge. For the first two years, she grew frustrated by the old guard, four councilmen who blocked just about every initiative she made.

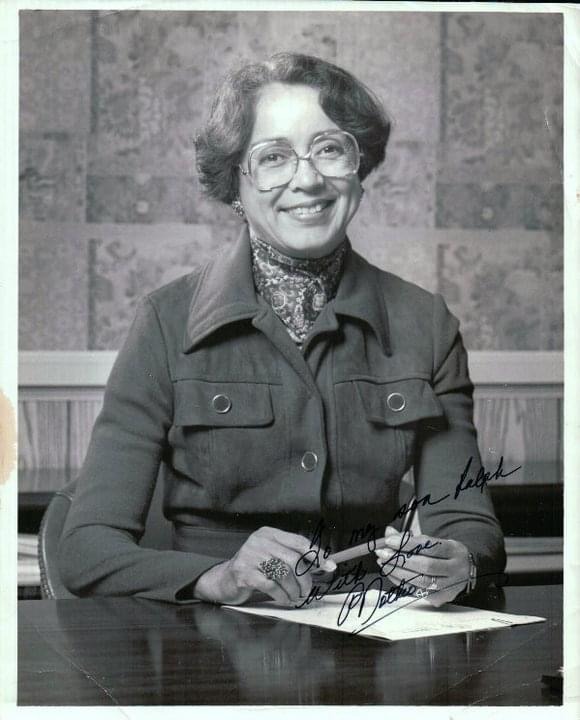

Things got better in 1971 when some of those Council seats changed hands. Her peers elected her Vice Mayor and she began to get things done, like overhauling St. Petersburg’s water system, improving hiring practices and instituting one of the country’s first mandatory seat-belt laws. She also fought unsuccessfully to have Black real estate owners compensated for past discrimination.

In 1972, at the Democratic national convention, she was a Florida at-large delegate who voted for George Wallace. State law mandated she had to vote for the segregationist Alabama governor on the first ballot because he had won the Florida primary. If George McGovern had not received the presidential nomination on the first ballot, she was all in for Hubert Humphrey.

Later that year, she ran for the State Senate and this time she lost. Back on City Council, she felt the urge to return to Tallahassee, primarily because our home had become a prime target of break-ins. One morning, while getting dressed for a City Council meeting, she found an intruder lurking outside our bathroom and banged him over the head with a hand mirror before he ran off.

So, it was no surprise in 1973 when Governor Reuben Askew got her to join the Commerce Department and she moved to Tallahassee. She soon became Deputy Secretary of Commerce and later, head of the state’s newly formed crime compensation committee.

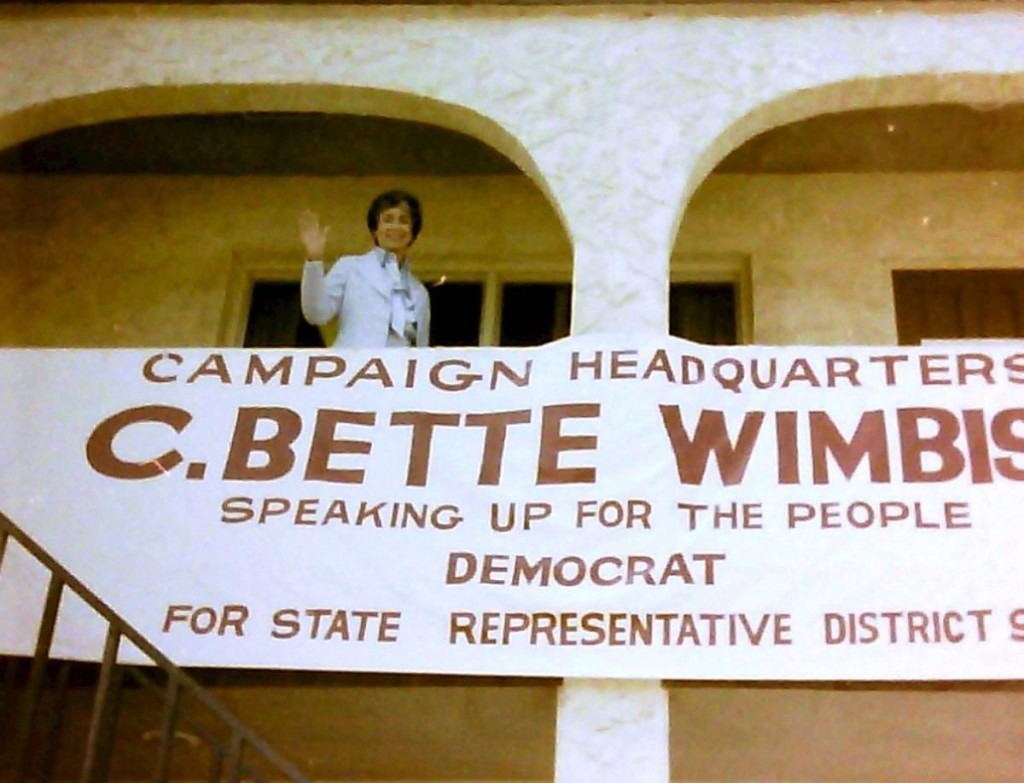

In 1982, while I was running around Europe, she decided to run for the State Legislature in a Tallahassee district, 250 miles from St. Pete. In a primary field of five, she surprisingly finished first and found herself in a runoff with another Black candidate, Al Lawson.

This was to be her toughest campaign, and I came back from Italy to be her chauffer. She took a lot of verbal abuse, some of it sexual involving the “C” word. Lawson accused her of being a “carpetbagger from St. Pete” even though she grew up in Perry FL, some 45 miles away, and attended high school and college in Tallahassee.

Lawson also said she was “too individualistic” and accused her of being “an elitist.” Even worse, he accused her of being “over educated.”

Still, the worst thing said about my mother was that she was trying to pass as white. Yes, my mother was light-skinned, but I can vouch there was nobody prouder of her heritage. Yet, call it a dirty trick or whatever, somebody dug up her voter registration card, which showed her race had been mysterious changed from “B” to “W.” That hurt her with Black voters.

She was also smeared in the rural White neighborhoods. From the far reaches of Liberty County, where vote-buying was common, we got wind of a hot rumor that my mom was “secretly married to a Jew.” We even got some anonymous phone calls asking if it was true.

Yeah, losing that election was hard for her. Twice, she went to the hospital that fall to be treated for diverticulitis, a painful intestinal condition that she may have passed on to me.

Always, though, if you asked her how she was feeling, her standard answer was “fair to middling.”

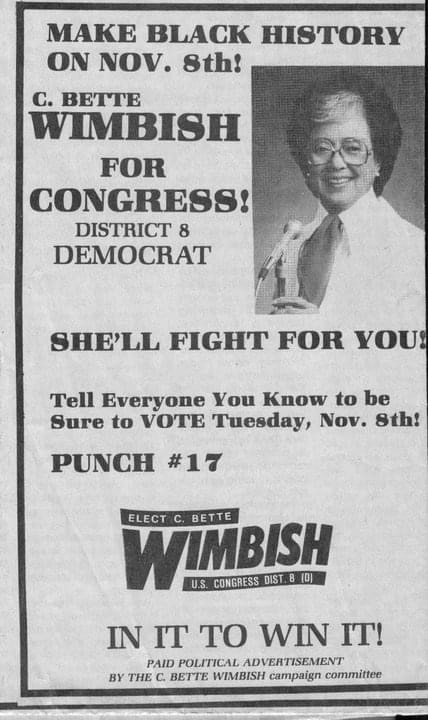

A few years later, Bette’s name surfaced as a candidate for the Florida Supreme Court, but she opted to return to St. Pete to run for Congress in 1988. She campaigned on environmental issues, drug education and women’s rights. She got 65,000 votes, but that was not enough to unseat Bill Young, the longtime Republican incumbent.

In the early ‘90s, she was planning on making a run for her old City Council seat just before our family suffered a pair of tragedies. My grandmother Ola Davis, the woman who raised her after my grandfather abandoned them shortly after she was born, died in 1991. Fourteen months later, my brother Terry died at the age of 32.

That really took the steam out of her, and she took a job as local counsel for the Florida Department of Social Services. On the side, she arbitrated labor law cases for the federal government until she retired in 2003.

But there was much more to my mom than just politics. She was a devout Catholic who never swore. I can honestly say I never heard one profane word leave her lips, even on that day I told her I was flunking geometry.

Bette had her quirks. Her great loves included fishing and crabbing, tennis, traveling, making gumbo, Dr. Pepper and Franco Harris, not necessarily in that order. She always was reading books by authors like Tom Clancy and Leon Uris when she wasn’t laughing hysterically at TV shows like Green Acres, Taxi and Northern Exposure.

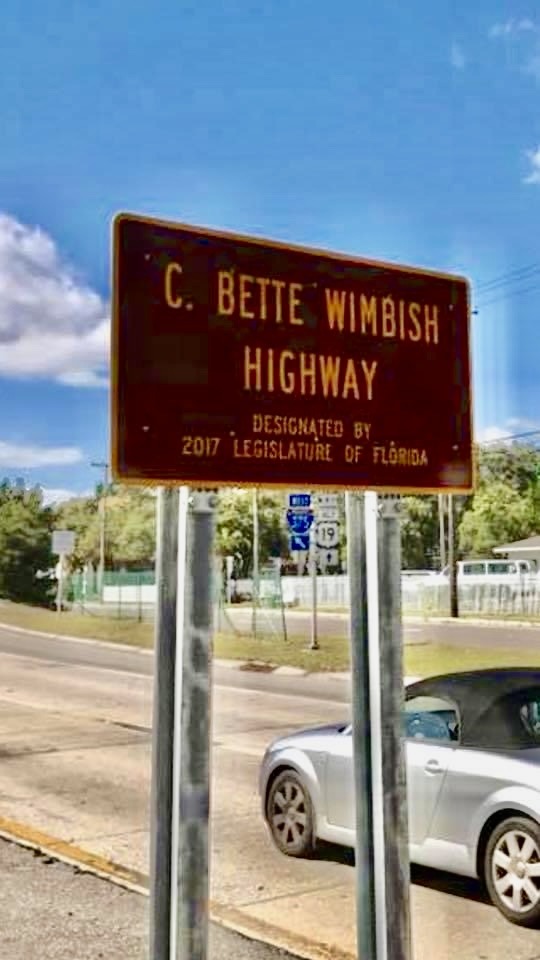

In 2017, the state named a busy highway [I-375] that leads into downtown St. Pete in her name. And my love of sports remains one of her lasting legacies. Growing up, she took me to baseball games, played catch with me in the driveway and watched football games with me on Sundays.

The only sport she didn’t really care for was golf. OK, she wasn’t perfect, but was she an exceptional woman?

You Bette!

Originally published in Heroes: Stories of Sports,

Courage and Class by Ralph Wimbish, Palmetto Press