Gallery Talk

May 11 from 6-7 pm

Details here

On View Through June 25

Leepa-Rattner Museum of Art

Tarpon Springs

Details here

This is an unabashed tribute to the late photographer and social historian Herb Snitzer (1932-2022). I was fortunate enough to be able to call him friend – but even if you did not have the privilege to know him personally you’ll want to read on to learn about a life well lived.

I take his long and meaningful journey through this world as inspiration to try to live my life with more intention and grace.

Snitzer was born in Philadelphia to parents who had escaped the Soviet pogroms in Ukraine. Despite growing up a son of refugee parents in a insulated Jewish lower middle class life, he tested into the prestigious all-boys Central High School.

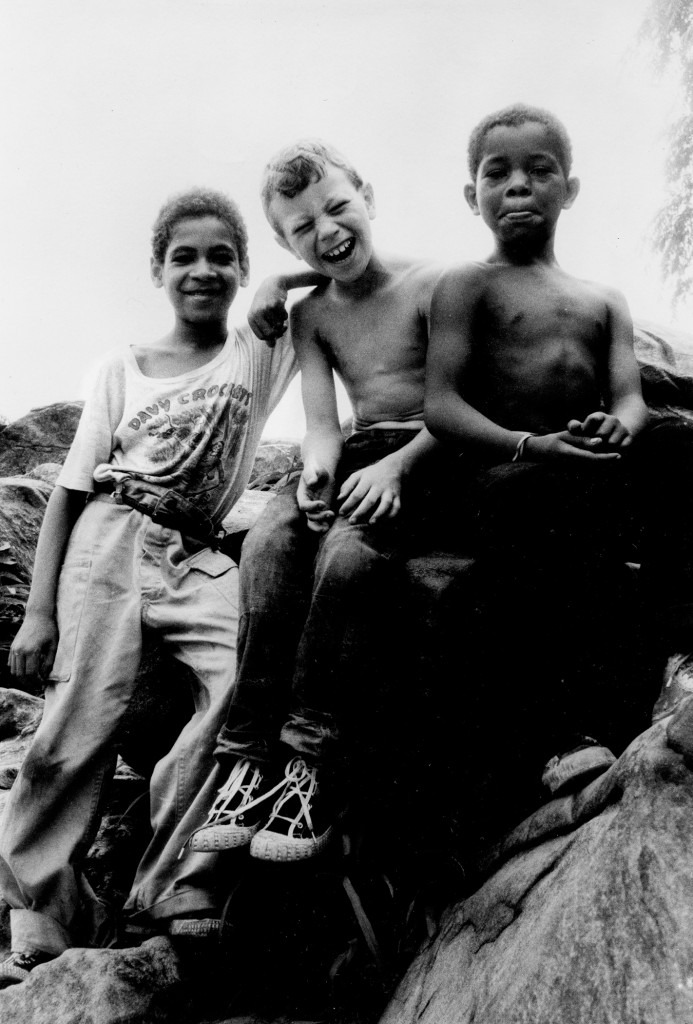

Perhaps because of this background he would tell stories of being sharply aware of the inequalities surrounding him even then due to race and class, not so much towards himself but towards the Black students he played football with.

Despite his traditional parents’ objections, he attended The University of the Arts (Philadelphia College of Art) focusing on drawing and began some photography, but was drafted into military service in 1953 during the Korean War.

He told stories of being against the war… against all violence… yet often wore a baseball cap with his veteran status proudly proclaimed. Not proud of the war, but maybe proud that he survived that difficult time.

Stationed in the American South, Snitzer brought his camera along and got a taste for capturing portraits of those around him. Even then, during the segregationist era of Brown versus Board of Education, he befriended people of all colors and backgrounds.

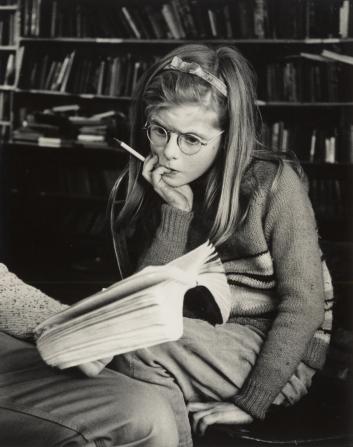

Returning to college he focused on photography. A passionate lover of music, his thesis series featured the Philadelphia Orchestra.

Upon graduation in spring of 1957, Herb headed to the rich cultural atmosphere of New York City. Needing a job and more experience, he flipped opened a telephone book and found a phone number for the esteemed portraitist Arnold Newman, who hired him as an assistant.

This apparently consisted of mostly carrying equipment, but undaunted he took advantage of the opportunity and learned from observing.

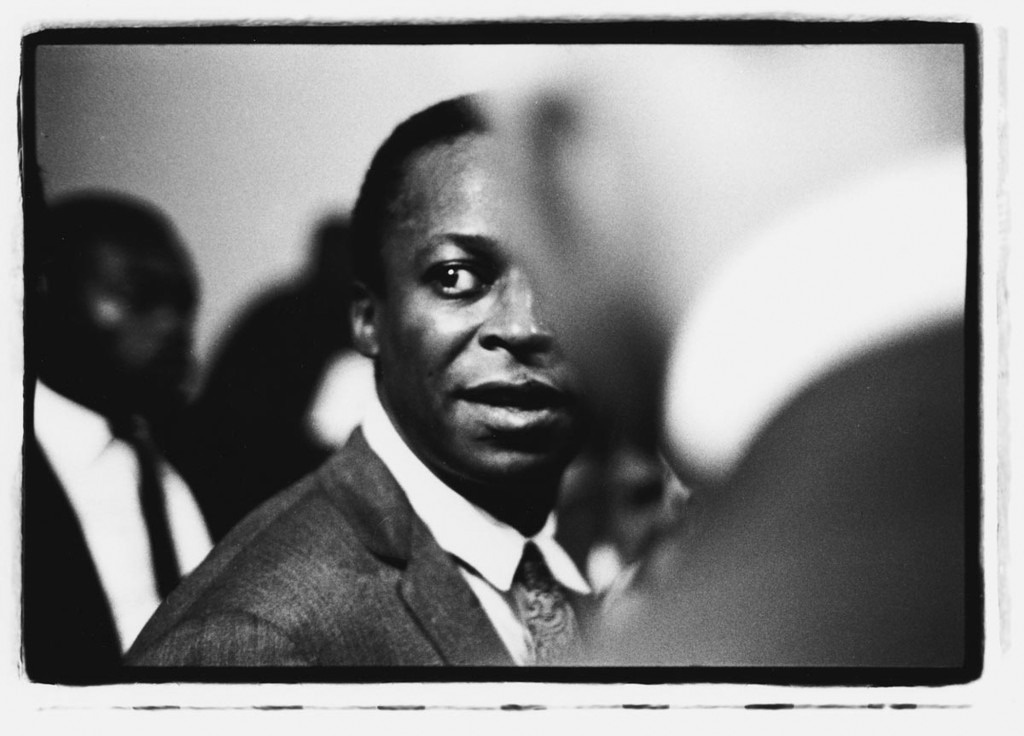

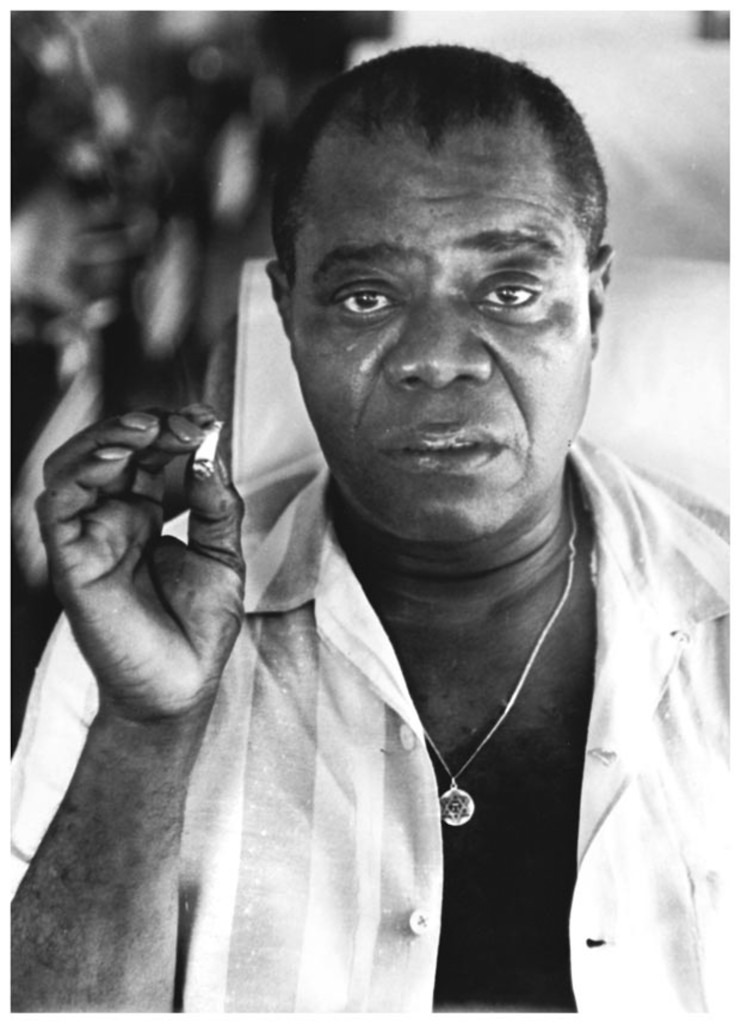

“… Those who sit for photographic portraits are vulnerable to the photographer. You look into their eyes and see their souls.

“Through lighting, pose, and that indefinable flash of recognition between sitter and photographer, if you are lucky, you can capture the essence of a sitter. And the results are remarkable.”

Snitzer spent seven very prolific years in NYC. An early series Four Seasons in Central Park was exhibited at the Museum of the City of New York. He met the esteemed photographer Edward Steichen, who as curator at MOMA purchased two of his photographs for the Museum’s collection.

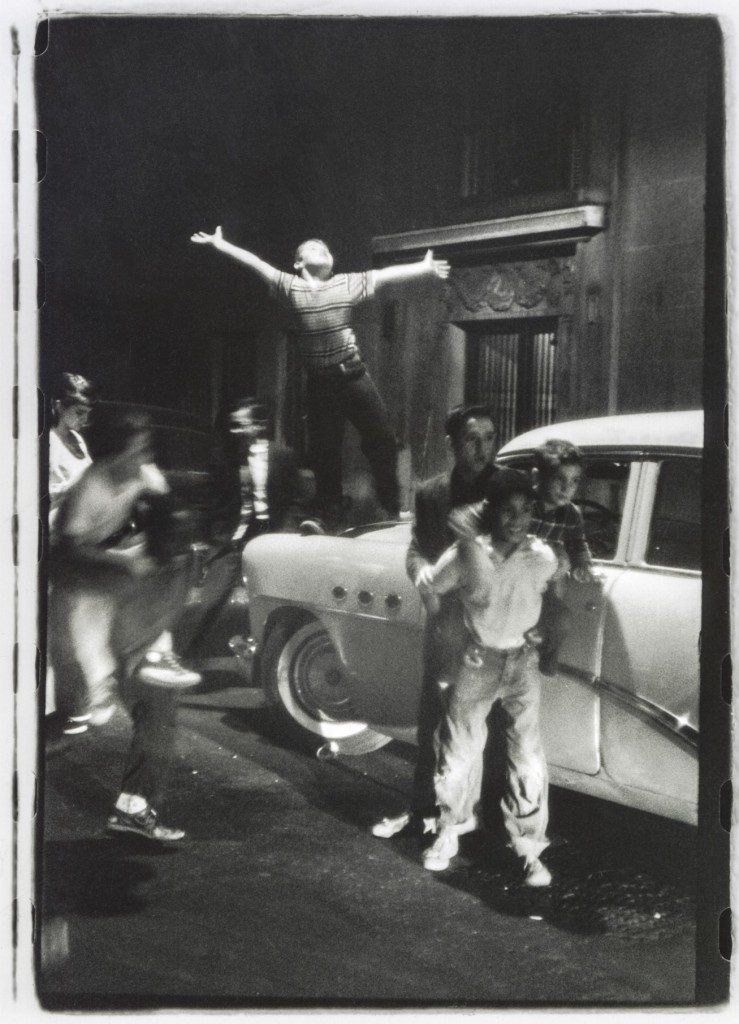

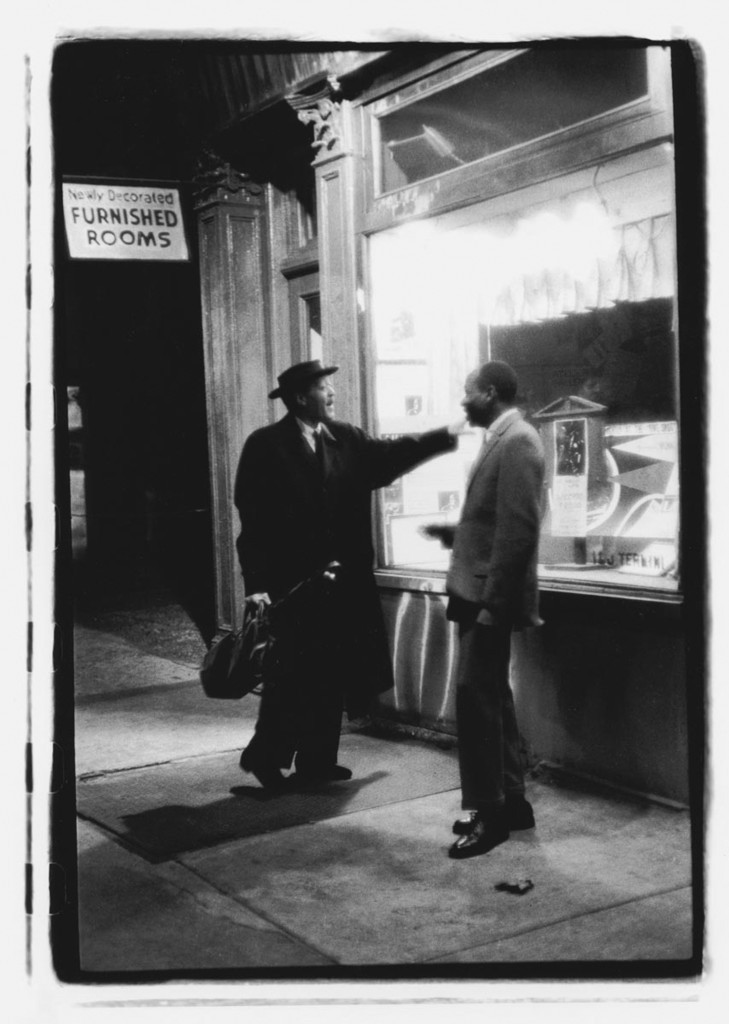

He wandered the streets near his Upper West Side home and in Greenwich Village and documented the people and activities on the streets around him. He made the rounds of assorted magazines selling his photos.

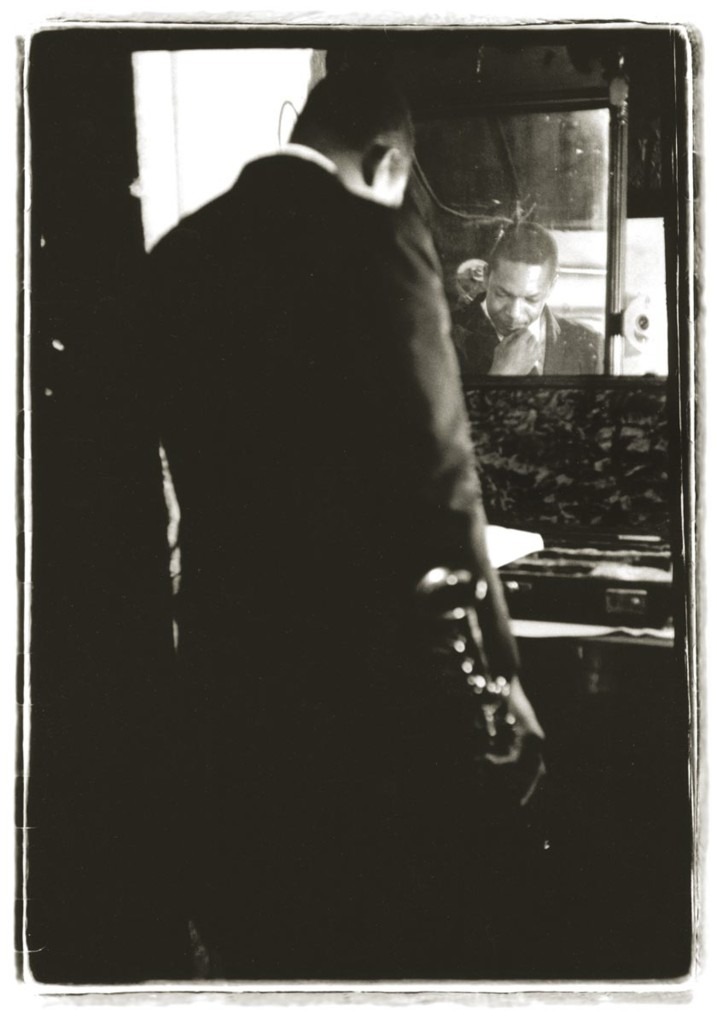

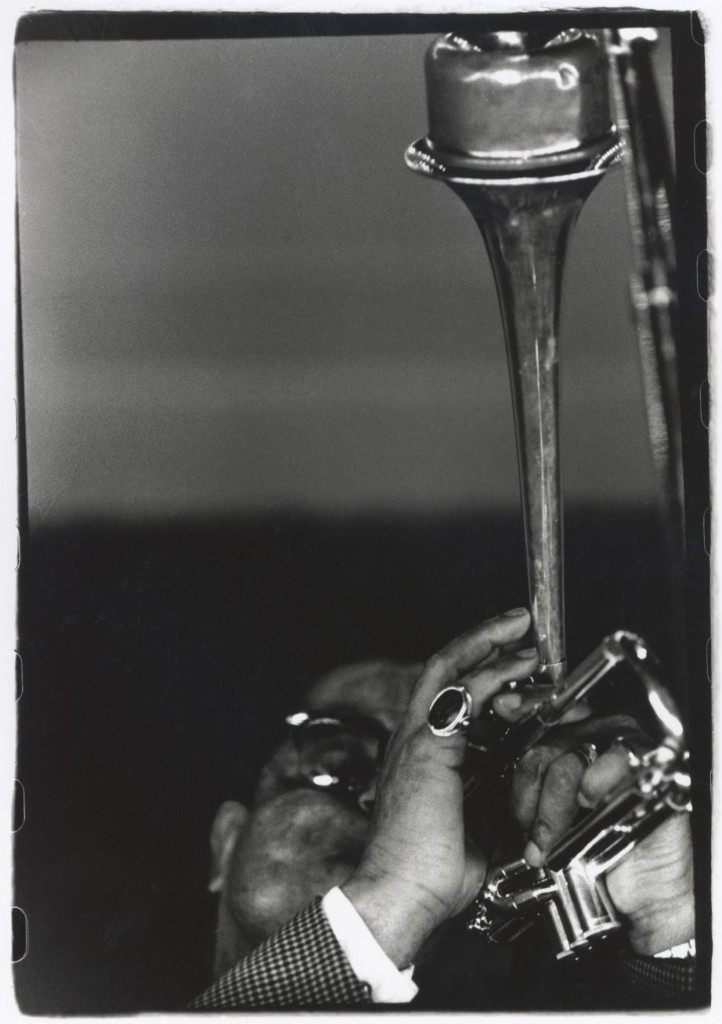

One of those publications was the jazz magazine Metronome. They offered Snitzer a freelance gig to go to The Five Spot Cafe and photograph the jazz great Lester Young. In Snitzer’s book Glorious Days and Nights: A Jazz Memoir, he shares how that night changed his life.

“Artists have life changing moments. For me, this was it. I had never heard a jazz musician up close like that. I just felt I was not in that room, but somewhere else. I could feel it in my chest – my own awe-inspiring, life-changing moment.”

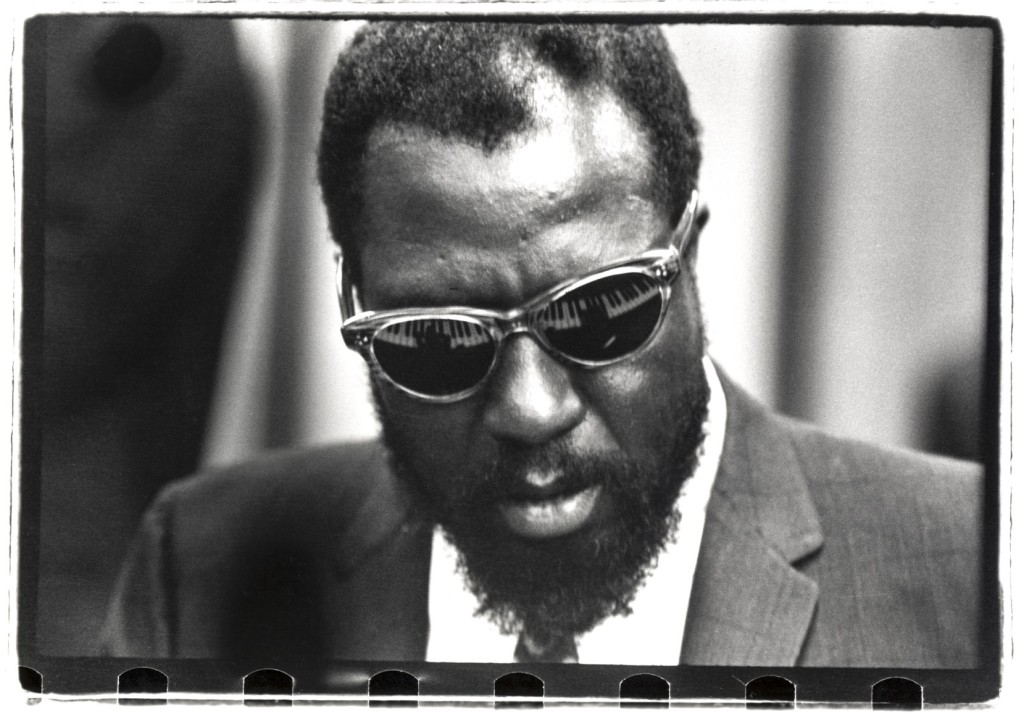

It was the beginning of an odyssey that cemented his place in photo history. He eventually became photography editor at Metronome, a gig that gave him access to some of the greatest jazz musicians of the time who played in small clubs like the Half Note, the Jazz Gallery and the Village Vanguard.

Herb was small in stature and had an easygoing nature, so he was able to slip into difficult places and get along with people easily. He was able to hang out with and photograph some of the all time jazz greats like Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Miles Davis, Thelonius Monk and Dizzy Gillespie.

He shot the cover art for an album with the amazing Nina Simone for Colpix Records, which started a friendship between the two.

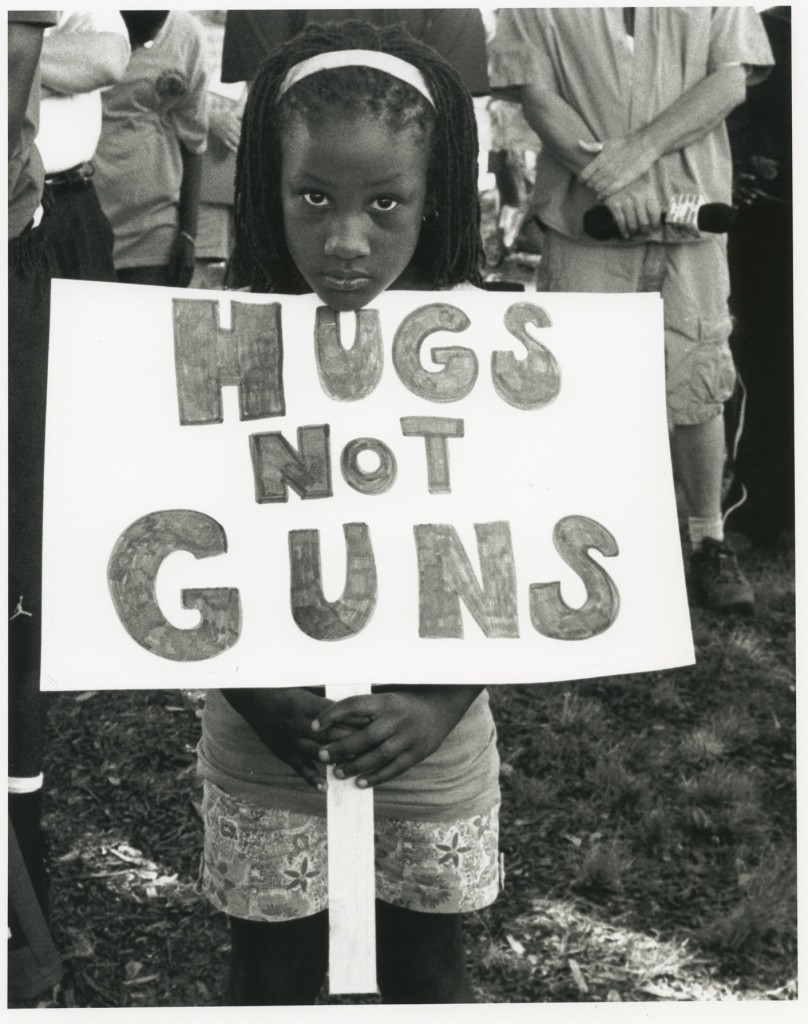

Running through all this work was Snitzer’s beliefs in freedom and dignity, equality and self-respect. He witnessed the prejudice that these Black performers encountered on a daily basis.

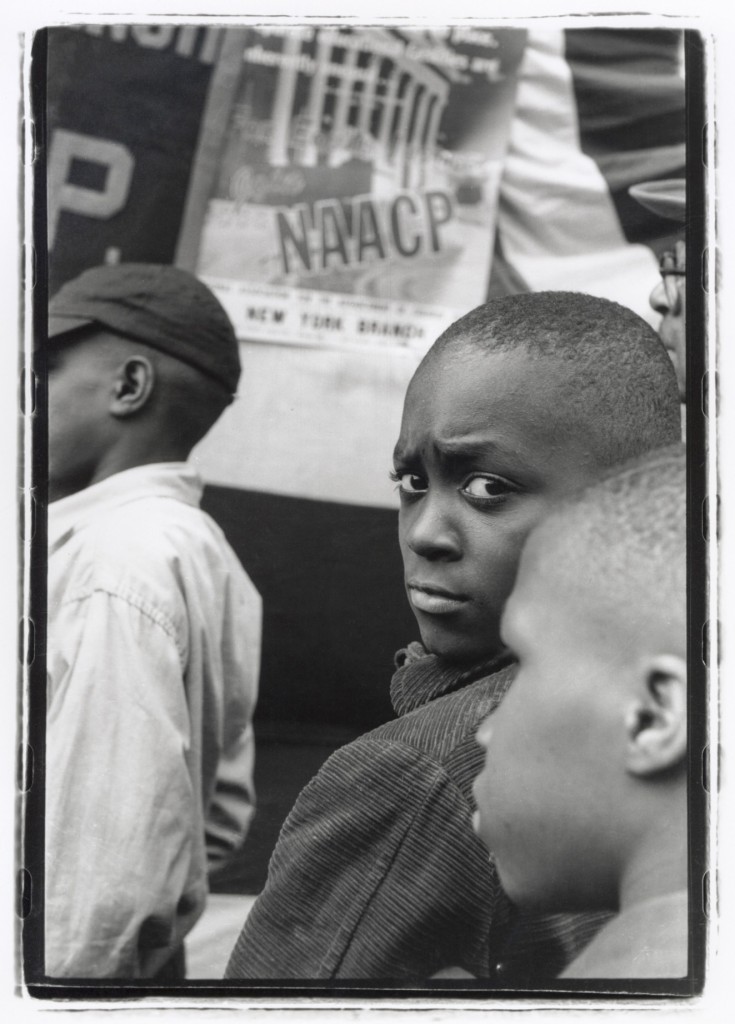

“Why am I, a middle-class humanist white guy so engrossed in the world(s) of African Americans and their drive for freedom and civil rights? My response is always the same – inequality for one is inequality for all. Racial hatred for one is racial (ethnic) hatred toward all others.”

The demise of Metronome Magazine set in motion a major change in Snitzer’s trajectory. He went to Europe and visited a progressive school he had read about, the Summerhill School in Leiston, Suffolk, England.

This visit eventually led to his writing a book about the subject, acquiring an MA from Goddard College and co-founding an alternative school in the American Adirondack Mountains based on the principles of participatory democracy and voluntary classes.

In the meantime he worked for a couple more years as a freelance photojournalist for such publications as TIME, Saturday Evening Post, LOOK and The New York Times, photographing such luminaries as the writer Tennessee Williams and the actress Bette Davis.

In the spring of 1964, he left NYC for the Adirondacks and spent 13 years as headmaster, helping scores of young people flourish and move onto college. Afterward he worked for four years for the Polaroid Corporation in Cambridge, Massachusetts and reunited with some of the jazz performers he had known in his early days like Dizzy Gillespie and Nina Simone.

In 1986, Nina invited him to accompany her to Bern, Switzerland to photograph some concerts she was performing there. This resulted in his being asked to photographed the International Jazz Festival Bern for the next three years capturing iconic images of musical greats like Sarah Vaughan and B.B. King.

“Jazz is more than wonderful music. It’s a statement about a people’s desire and thirst for freedom – and with freedom the sweetness of individuality and sense of self worth.”

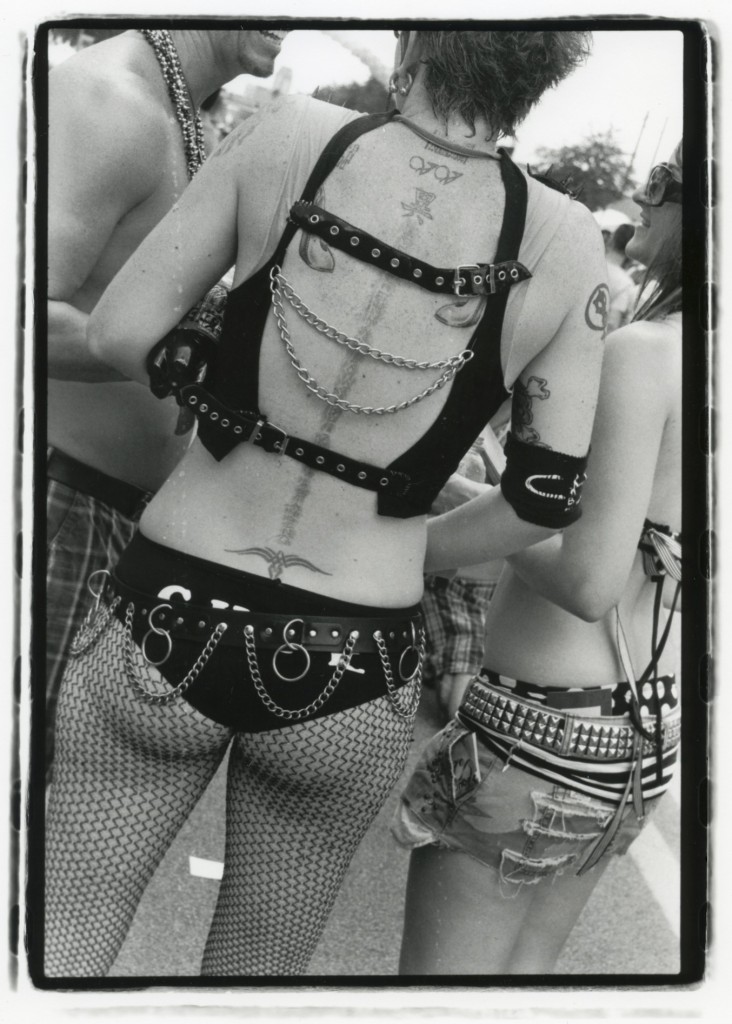

In 1992 Snitzer moved permanently to St. Petersburg, Florida. While his jazz portraiture days were behind him, his desire to photograph the people around him and give voice to the struggle for freedom and inequality were not.

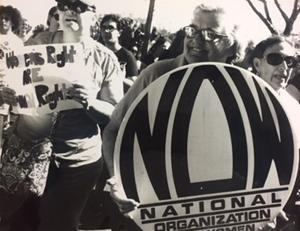

He joined the NAACP and made captivating photographs of demonstrations, protests and gay pride parades. Empowering his subjects with dignity and capturing playful spontaneity.

Snitzer died on New Year’s Eve of 2022 at the age of 90, leaving behind his wife, painter Carol Dameron and her delightful children Eva, Tito and Amadeus, as well as his accomplished children from an earlier marriage Werner, Susie, Lisa, Laura and Sigrid, plus many wonderful grandchildren, nieces, nephews and cousins.

Herb Snitzer made an impact on those who knew him with his sharp mind and captivating stories. He also leaves behind thousands of incredible images, created over a lifetime of picture making.

As they wrote at his memorial, “We love you, Herb. You have made an immeasurable difference in the world.”

Gallery Talk

The Photography of Herb Snitzer with Robin O’Dell

May 11 from 6-7 pm

Leepa-Rattner Museum of Art

Details here

Through June 25 at the Leepa-Rattner Museum of Art

Herb Snitzer: In the Present

600 E. Klosterman Rd.

Tarpon Springs FL 34689

Details here

All images (c) Herb Snitzer