January 25, 2021 | By Tony Wong Palms

Through March 14

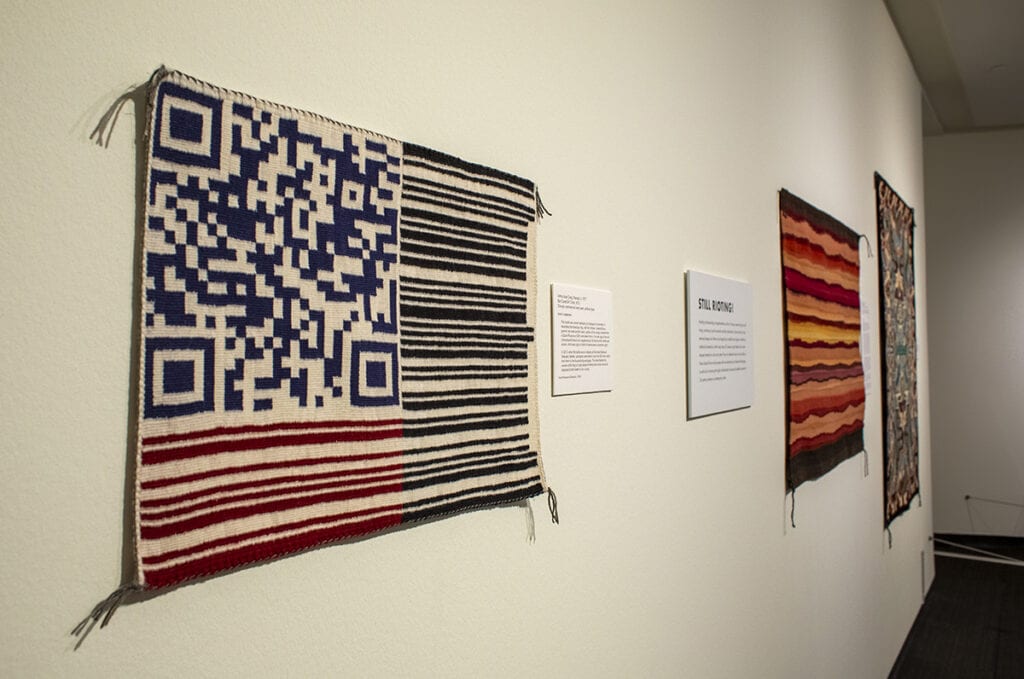

Museum of Fine Arts, St Pete

Details here

. . .

. . .

The Museum of Fine Arts in St. Petersburg has converted their galleries into a Navajo textile heaven, welcoming visitors with chief blankets, sarapes, saddle covers, transitional textiles, contemporary weavings – and story of a people creating beauty in the aftermath of an existential crisis.

Anthropologists speculate that the Navajos learnt weaving from the Pueblo people. Navajos tells of learning weaving from the Spider Woman, with the first loom being of sky and earth, and the weaving tools made of sunlight, lightning, white shell and crystal. This explanation is equally plausible, and a truth more compelling for its deeper undertones and echoing creation mythologies.

From that early apprenticeship era, the Navajo developed into master weavers, passing knowledge from one generation to the next, first creating pieces primarily for ceremonial use and for limited trading with their immediate neighbors, evolving into textiles highly sought after by peoples far beyond their borders.

This exhibition, titled Color Riot! How Color Changed Navajo Textiles, explores one period of this long history. Organized by the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona, whose curatorial team collaborated with three scholars from the Navajo Nation – Ninabah Winton, Velma Kee Craig and Natalia Miles.

These scholars participated in every phase of the exhibition, from project concept development to curation to exhibition installation, wrote the labels and didactic panels, infusing it with an inner voice that only people telling their own stories can convey.

Early Navajo weaving can roughly be divided into three main periods – early classic period from 1700-1804, classic period from 1804-1880, and the very aptly named transitional period from 1864-1900. Since then, there have been several periods of development, like the Dazzling Eye period, the rug periods and contemporary art movements, several examples of which are included in the exhibition.

The weavings on display are primarily from the transitional period, in particular the creative flourish after the Navajo were forced to march to internment camps in 1864, as curator Velma Kee Craig writes:

“The textiles presented in this exhibition are creations of weavers who wove for themselves — they are vibrant and unrestrained in both color and design. They were woven after a time when Navajo men, women and children were themselves marched hundreds of miles out of their homeland to be held in an internment camp.

Handspun wool, aniline dyes, Collection of Carol Ann Mackay

“These weavers knew first hand the looming heaviness and darkness of mass erasure, and more so than at any previous time, they created for themselves, for their families, and for the 2,500 Navajos who never made it home again.”

The colors Velma Kee Craig mentions are from industrial processed yarns using aniline and other synthetic dyes, very much contrasting with traditional hand-spun yarns and natural dyes, or simply the original color of the wool as grown on the sheep.

‘Transitional’ then takes on several meanings. It’s a threshold moment, from traditional labor-intensive yarn spinning and dyeing to purchasing industrial yarns. But the time-consuming weaving process continues – from simple bold patterns to more complex use of colors and designs. . . from the traditional tribal life, to surviving interment camp life, to learning how to navigate the influx of foreign settlers in and around their homeland. . . from inter-tribal trading to wider commercial ventures. . . from artisans to artists.

Scholar/curator Natalia Miles had this to say about the Dazzling Eye Period, 1880-1900, which is more a chapter within the Transitional Period than a separate independent movement:

“I did not know that the term ‘eyedazzler’ was originally used. . . as a descriptor for these colorful, ‘unmarketable’ weavings that briefly thrived after Hwéeldi (the Long Walk and Boswell Redondo imprisonment).

“In my mind, the term had always been meant as pleasant and positive, and I find it humorous that these traders gave these ‘undesirable’ weavings such an attractive name. In these weavings there is a true sense of the artists’ unbridled creativity and freedom in their color schemes and layout.”

Dazzling Eye can join the long list of derisive nomenclature that outsiders use when encountering something they don’t like or understand. ‘Impressionism’ and ‘Fauvism’ are also terms originally meant as ridicule, that are in art history books now.

If Color Riot! can be described with a Venn diagram, it would show many overlapping circles — circles of anthropology, design language, color theory, artisanship, art, animal husbandry, tribal traditions, weaving industry, fashion/styles, gender roles, trade routes, colonialism, government oppression, internment camps, the Navajo people, self identity, symbolism, and the American West landscape.

In short, this is a glorious exhibition. Of the many books that have been published on Navajo weaving, scores of TV documentaries, and websites linking to more articles and images, all are recommended – but all fall short of this face to face encounter.

Perhaps one lacking aspect, one unfulfillable desire, is the ability to touch and feel these fabrics – a sensory dimension, very understandably, not possible in a museum exhibition. For this, I will need to make another journey.