April 14, 2021 | By Steven Kenny

Through August 22

Museum of Fine Arts

Details here

Confession. I am an antiquities smuggler. Sort of. Back in the mid-1980s when I was studying in Italy, I visited Hadrian’s Villa (built in the year 120) outside Rome. The outdoor walkways were covered with what seemed to be gravel. On closer inspection, the crushed stone turned out to be millions of pea-size “tesserae” (the Latin plural noun for the individual tiles that make up mosaics). I surreptitiously put one in my pocket and brought it back to the States. My conscience has never recovered.

The profitable business of pilfering ancient, historical artifacts has been practiced for millennia. Tombs of Egyptian kings, Aztec and Inca temples, you name it, almost all have been plundered at one time or another. Many museum collections around the world contain questionably obtained objects. The most well-known of these may be the Elgin Marbles in the British Museum which were removed from the Parthenon in the early 1800s. To this day Greece is doing all it can to the have the sculptures repatriated.

Rest assured, however, all the mosaics in the MFA exhibition were originally obtained through what is known as a partage agreement (from the French “partager” meaning “to share”) between the Committee for the Excavation of Antioch, led by Princeton University and the Syrian government.

So it was with great curiosity that I went to see Antioch Reclaimed, the new exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts in St Petersburg. What I found was a beautiful, educational and very entertaining presentation built around the museum’s collection of five mosaics from the Greco-Roman city of Antioch, founded by one of Alexander the Great’s generals, Seleukos I, in c. 300 BCE.

Notably, when purchased from Princeton in 1964, these five pavements were the very first objects to become part of what is now the museum’s permanent collection. Oddly, soon after that, three of them were buried under the museum lawn until being disinterred a second time in 2018.

. . .

. . .

This exhibition meticulously tells the tale of how a team of archeologists, led by Princeton University, excavated an area in what was then a wealthy suburb of Antioch. Photographs taken during the 1932-1939 excavation document the backbreaking labor required to unearth the pavements. A black-and-white silent film plays continuously giving an incredible glimpse into what daily life was like in the city of Antioch and at the dig site while the archeologists were working.

. . .

. . .

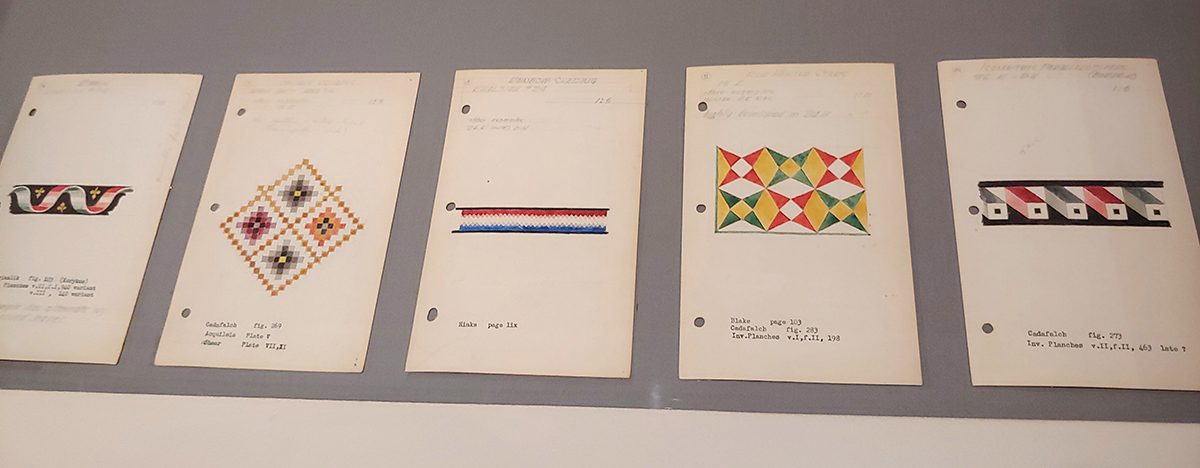

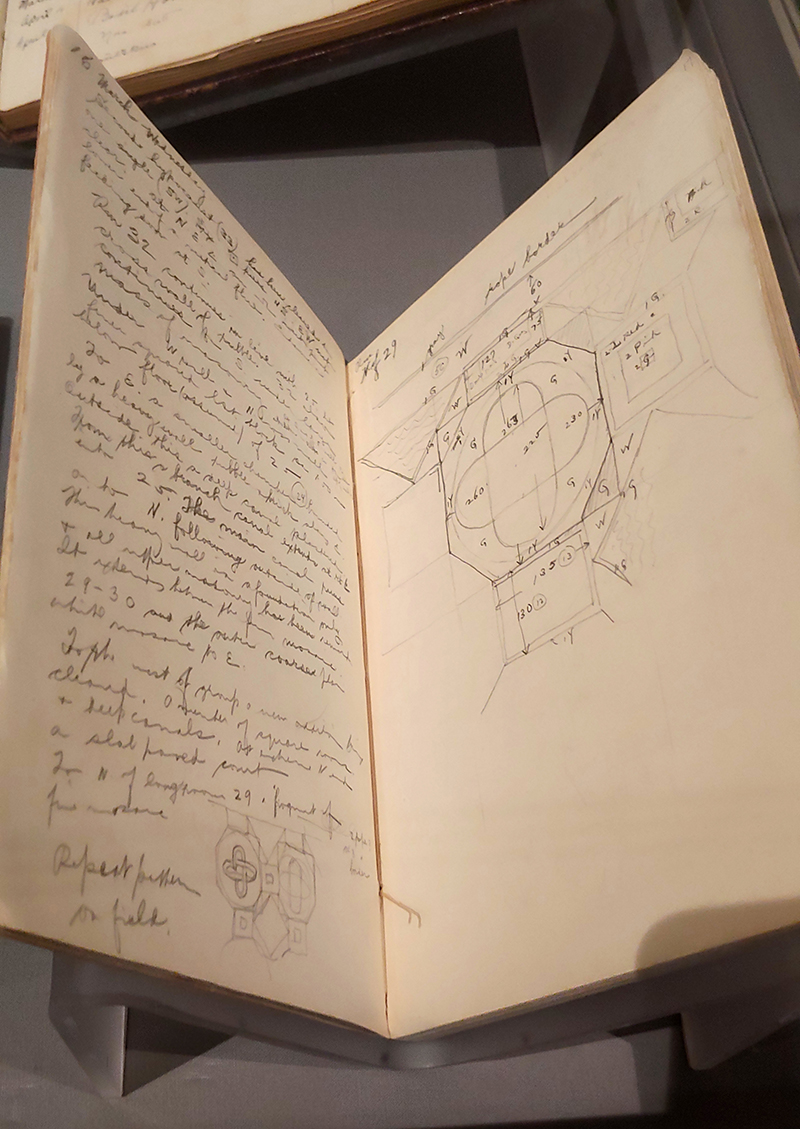

Original journals, sketches, find cards, notebooks and a guestbook demonstrate just how thoroughly each step of the endeavor was recorded and cataloged.

. . .

. . .

. . .

Floor-to-ceiling photos show the original location of each of the pavements prior to removal, giving a sense how they may have appeared underfoot in the posh homes they occupied.

. . .

. . .

A detail that may go unnoticed is how the mosaic tiles are arranged. In the House of the Drinking Contest mosaic they actually radiate outward in concentric circles from the point at which the white diamond shapes meet.

Looking closely it also becomes apparent just how much labor goes into making mosaics on this scale. Look again at the single tessera above and multiply that by millions. Each had to be shaped by hand, sorted by color, arranged in place and then cemented in place. Mind boggling!

. . .

. . .

Rounding out the exhibition are other fine pieces of sculpture on loan from the Princeton University Art Museum. Together with the mosaics we have a sense of what it may have been like inside one of the Antioch villas.

. . .. . .

. . .

All in all, this exhibition does a fantastic job of going beyond physically displaying the mosaics. We travel back to the 1930s and feel the excitement of discovery with the archeological team. We’re allowed to look over the shoulders of those inspecting and cataloging each object as it’s pulled from the earth. So put on your pith helmet and head over to the Museum of Fine Arts to experience this revelatory exhibition.