. . .

I went to a tea party at the Dalí last week with my friend Anthea Penrose. Born just a month apart on two different continents (Anthea is from England), we were celebrating our upcoming birthdays.

We sat at a small table in the Raymond James Room where we could see the museum’s new Dalí Alive 360°dome through triangular glass windows.

A woman in a floral hooped skirt and a black bolero jacket offered us a choice of teas from a tray – Earl Grey Lavender, Florida Orange Blossom and Carrot Cake. I chose Orange Blossom and plopped the oversized tea bag into a porcelain cup.

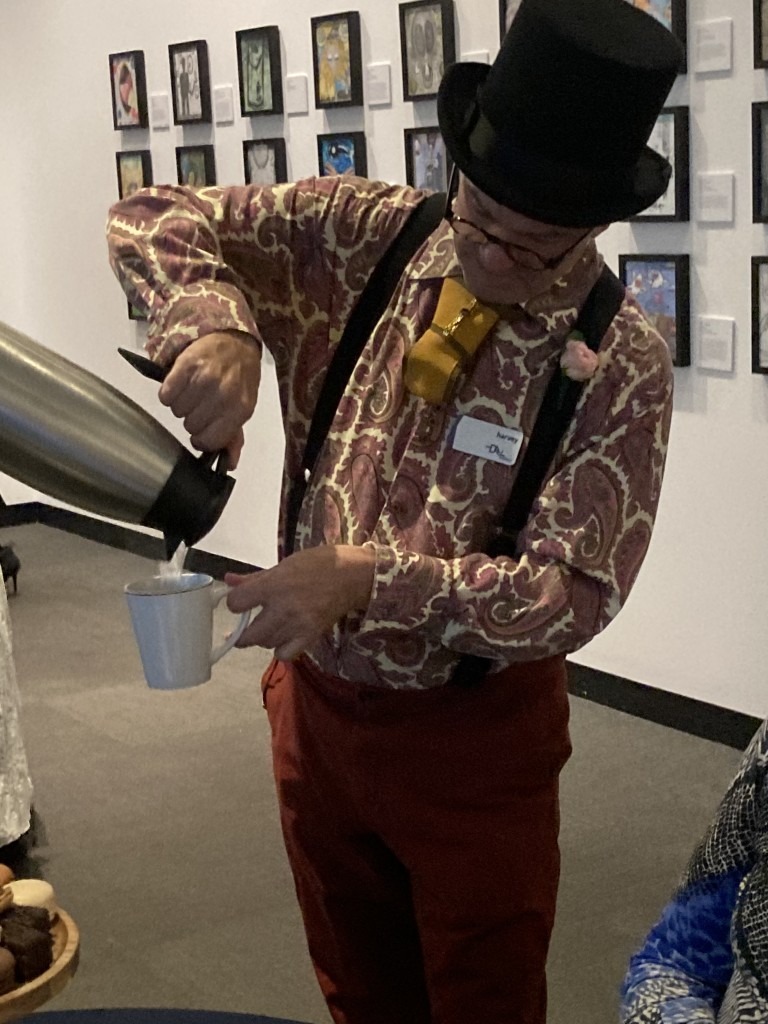

A man in a top hat and suspenders poured steaming water into my cup and then returned continuously to top it off as I ate from a three-tiered serving stand set in the middle of the table. The top tier was filled with petits-fours, the middle, with flaky triangle pastries, the lower with classic English tea sandwiches – egg salad and, of course, cucumber sandwiches with smoked salmon.

In addition to the tea and edibles, the museum’s Zodiac Membership Committee, the all-volunteer group that organized the members-only event, set up a display of Victorian objects (a Victorian mesh bag reminded me of one my mother collected) and a corsage-making booth.

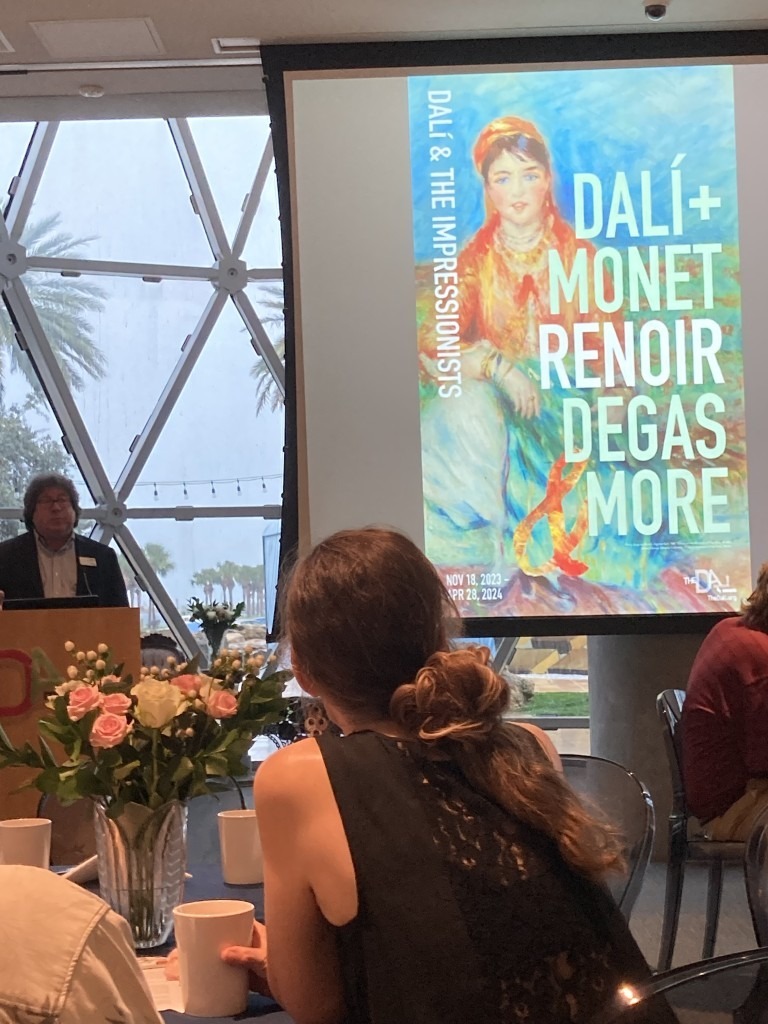

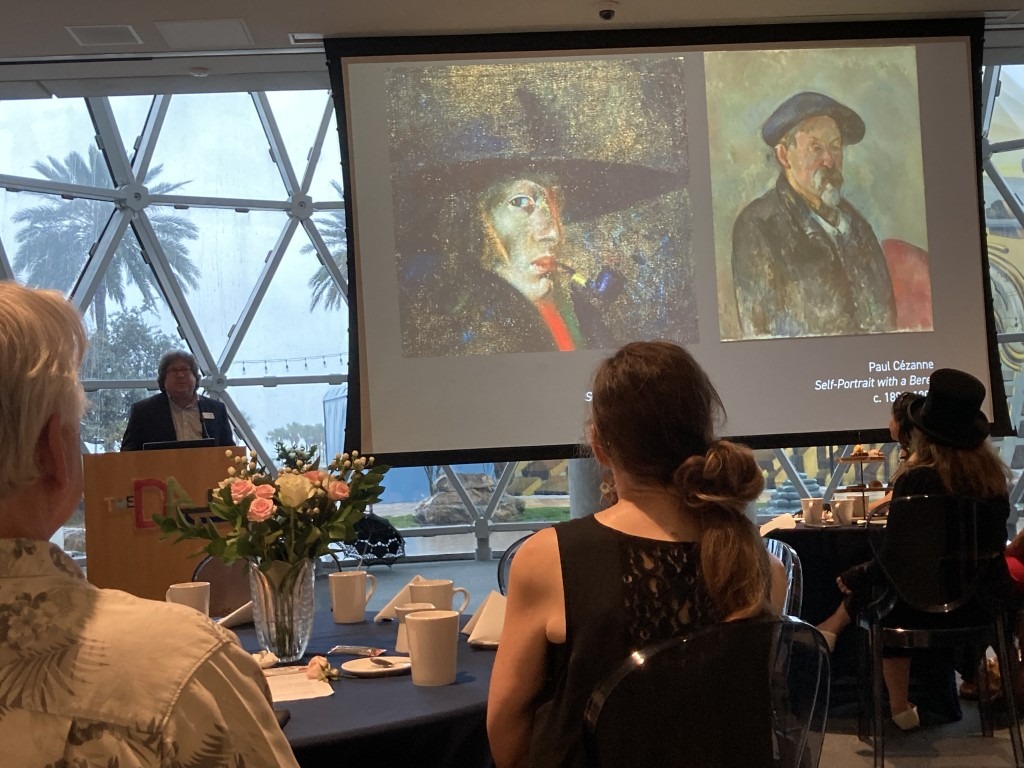

We also were treated to a talk by Curator of Education Peter Tush on the museum’s current special exhibit Dali & the Impressionists and were invited to view that exhibit after hours.

At first a Victorian tea party and an exhibit on Impressionism seemed like an odd pairing. The Impressionist painters, after all, had famously rebelled against the stuffy world of tea and crumpets in the 19th century, rejecting the rigid rules of the Academy that great art was filled with stylized religious or mythological figures.

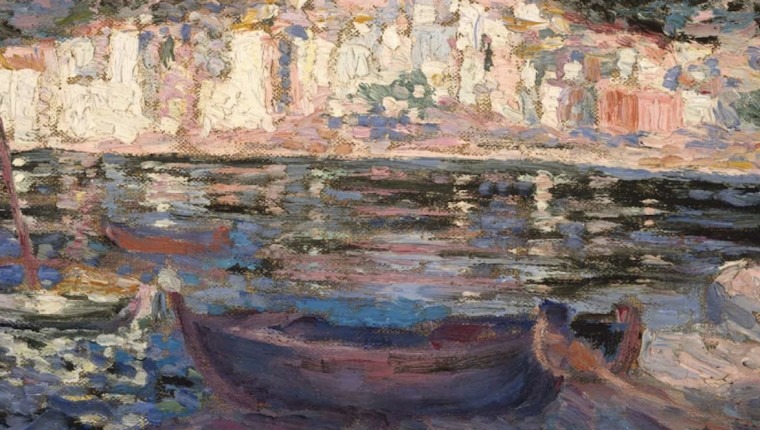

They opted instead for the great outdoors where they painted “en plein air.” They wanted to lose themselves, as Dalí put it “in the mystery of light, color and life.”

But as Tush’s talk demonstrated, the exhibit — and our afternoon at the Dalí — was all about surprising pairings.

Take our table companions, for example. They were a couple whom neither of us had ever met. He was a professor of journalism at USFSP. She was a psychotherapist. But as we chatted over tea snacks, I realized that I had not only read the professor’s book on scrub jays, I had written about his book twice for this magazine (see Reading My Age: 73 Books in 2022 and Writing About Things With Feathers).

It was a pair-up that would have delighted the Surrealists’ love of chance encounters.

The exhibit Dali & the Impressionists: Monet, Renoir, Degas & More (which is on view until April 28) itself is a study in juxtaposition, placing the early work of Dalí next to the works of his older mentors. It celebrates Dalí’s initial love affair with the Impressionists, who inspired him to become a painter – but it also tells the story of his eventual rebellion against those early influencers.

The show reminds us that every generation first tries to imitate their predecessors but inevitably rejects them to forge their own style. Or as Picasso was said to advise, “Learn the rules like a pro, so you can break them like an artist.”

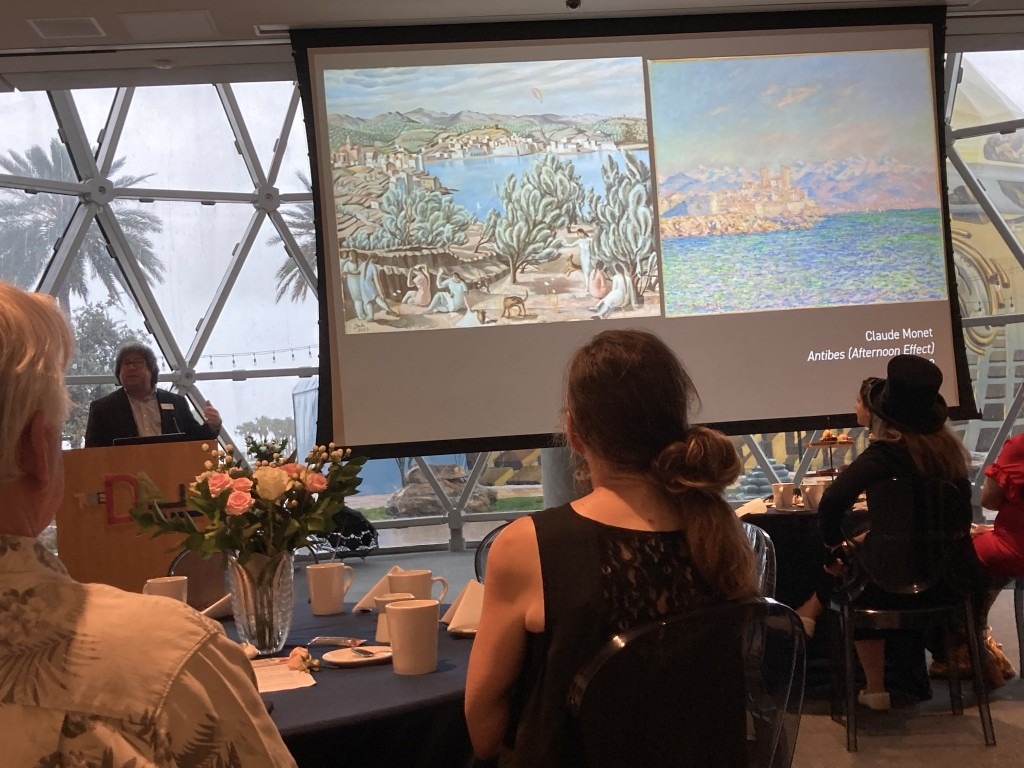

To illustrate this point, Peter Tush first showed us slides of paintings by an impossibly young Dalí side by side with the likes of Renior and Alfred Sisley. Port Alguer from Riba d’en Pitxot (1918), painted by Dalí when he was 14 — 14 years old! — is juxtaposed with Renior’s Rocky Crags at L’Estaque (1882).

The Lane to Port Lligat with View of Cap Creus (1922), painted by an 18-year-old Dalí is set alongside Sisley’s The Loing at Saint-Mammès (1882). Amazingly, both Dalí paintings hold their own. You would never guess they were painted by a teenager.

Then Tush clicked on a slide of Dalí’s 1923 painting, Cadaques, paired with a quintessentially Impressionist view of another port city by Claude Monet – Antibes: Afternoon Effect (1888). In Dalí’s painting, blocky shapes and geometric forms invade the landscape. At 19, embracing Cubism, Dalí is already moving away from his early Impressionist mentors.

The final pairings Tush’ showed us are two works from 1924 – Dalí’s Bouquet (L’lmportant c‘est la rose) and Henri Matisse’s Vase of Flowers. Here Dalí is no longer competing with the Impressionists of the 19th century. He’s being compared to a contemporary. Matisse was in his mid-50s in 1924. Dalí was only 20, one year away from his first solo show in Paris.

As I toured the exhibit to see the actual paintings Peter Tush had showed us in his PowerPoint presentation, age (and my upcoming 75th birthday) was on my mind.

I stopped a while before a pair of self-portraits and took a long, hard look – one by a brash, emerging artist (Dalí’s Self-Portrait, Figueres) and another by a well-established, celebrated master (Paul Cézanne’s Self-Portrait with a Beret).

Peter had pointed out that both are wearing hats, but Dali’s is clearly an affectation (as is the pipe he sports, which he never lit). Dalí is 17, with his whole career ahead of him. He is inventing himself.

Cézanne is 61 and the weariness of his long life marks his face. He has only six more years to live, but he doesn’t know that. So he continues to do what he does best – he paints.

It occurred to me that this pairing of self-portraits is an inspiration to both the young and the old artist. The young can see their future. The old, their past. They are tributes to the beginnings and ends of creative lives, each with its own drawbacks and joys, each with its own powers.

At the end of the Impressionist show, there was a chance to create our own self-portraits. You sat in front of a machine to have your photo taken and then, by the wizardry of AI, your image was transformed into a “one-of-a-kind Impressionist work of art.”

The museum had offered something similar in 2022 during the Picasso and the Allure of the South exhibit. My self-portrait back then — a Cubist version of myself — gave me a surprising glimpse into the future. . . I looked like my mother.

This time the opposite occurred. Although I would hardly call the Impressionist self-portrait I created via AI a “work of art,” this time I found myself peering into the past. The AI machine had time traveled, offering up a younger version of myself.