In today’s rapidly evolving technological landscape, embracing the unknown becomes even more imperative. As we immerse ourselves in the digital age, we also venture into the era of data. The vast expanse of information coursing through our interconnected world provides artists with unprecedented opportunities to craft narratives that give meaning to this abundance. Artists, being sense-makers, possess the unique ability to transform abstract ideas into tangible experiences. But how can artists bring data to life in tangible ways?

During the early days of the internet, as information started its digital transformation, Hiroshi Ishi and Brygg Ullmer published a groundbreaking paper titled “Tangible Bits.” This paper had a lasting impact on the field of human-computer interaction (HCI). Their mission was clear: to bridge the gap between the virtual world and the physical environment, as well as between different aspects of human activities [1]. Their vision still resonates and continues to guide the evolution of HCI.

As a new media artist using code as a creative medium, I am deeply intrigued by HCI research and its exploration of making the abstract digital domain more tangible. I find this line of inquiry especially relevant to art as artists possess a remarkable ability to establish meaningful connections between their hands, minds and materials. Prior to his insights on Tangible Bits, Hiroshi drew inspiration from the artistic objects housed in Harvard’s Scientific Instruments Collection. This inspired him to reflect on computation in relation to the tangible objects crafted by our ancestors from wood, metal, and glass. These objects served purposes such as measuring time, predicting celestial movements, or creating geometric forms [1].

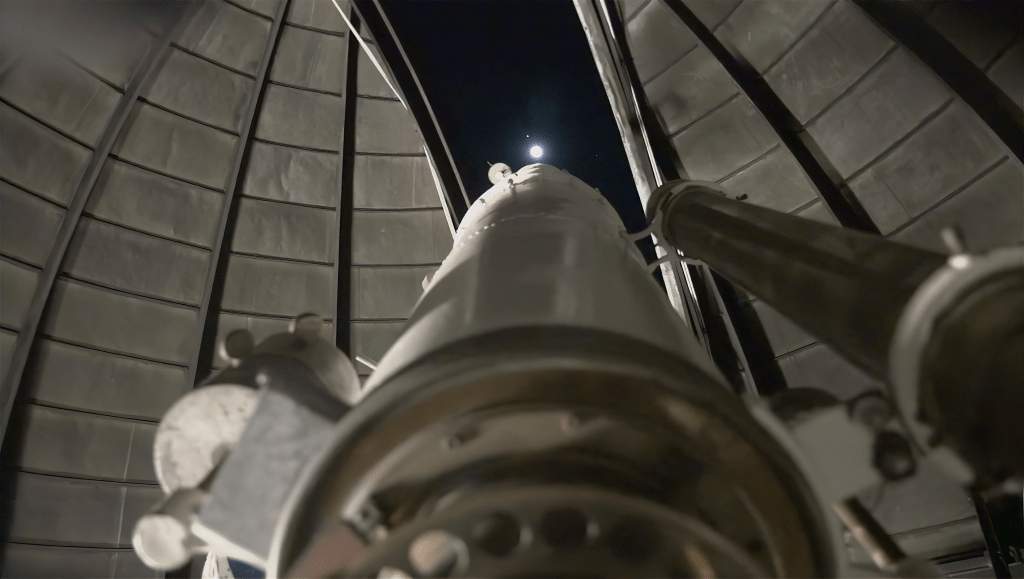

Hiroshi’s initial inspiration with scientific instruments reflects my own experience. Exploring the collection of 17th-century instruments at Brown University’s Ladd Observatory inspired me to create the Observatory Project. In this endeavor, I sought to transform the Ladd Observatory into an immersive exhibition, intertwining visual mechanisms, sculptural objects, and musical performances to celebrate the boundless realms of observation, imagination, and discovery. Over the course of a year I pulled together 20 other artists and scientists, and collaborated with them to take over the Observatory. I deliberately chose this historic site, which houses a magnificent 12-foot refracting telescope, as it symbolizes the triumphant union of art, design, and scientific exploration. The invention of the telescope in 1608 marked a pivotal moment in harnessing the power of art and design to unravel the mysteries of the universe and make our abstract notions of it more tangible [2].

On the enchanting opening night of the Observatory Project, the ethereal notes of George Crumb’s “Music for a Summer Evening,” performed by a member of the esteemed Boston Philharmonic, reverberated through the corridors of the Ladd Observatory, accompanying visitors on their extraordinary journey. As a participating artist myself, I contributed several site-specific installations that transformed the Observatory’s rooms into alluring chambers, playing with the interplay of mirrors, lenses, cameras, and projections, inviting participants to delve into the enchanting realm of scientific observation. Ultimately, this immersive exhibition embarked on an engaging exploration, melding the past and the present, bridging artistic innovation and scientific curiosity. The Observatory Project celebrated the captivating synergy between art and science, inviting all to experience the mysterious unknown in many tangible ways.

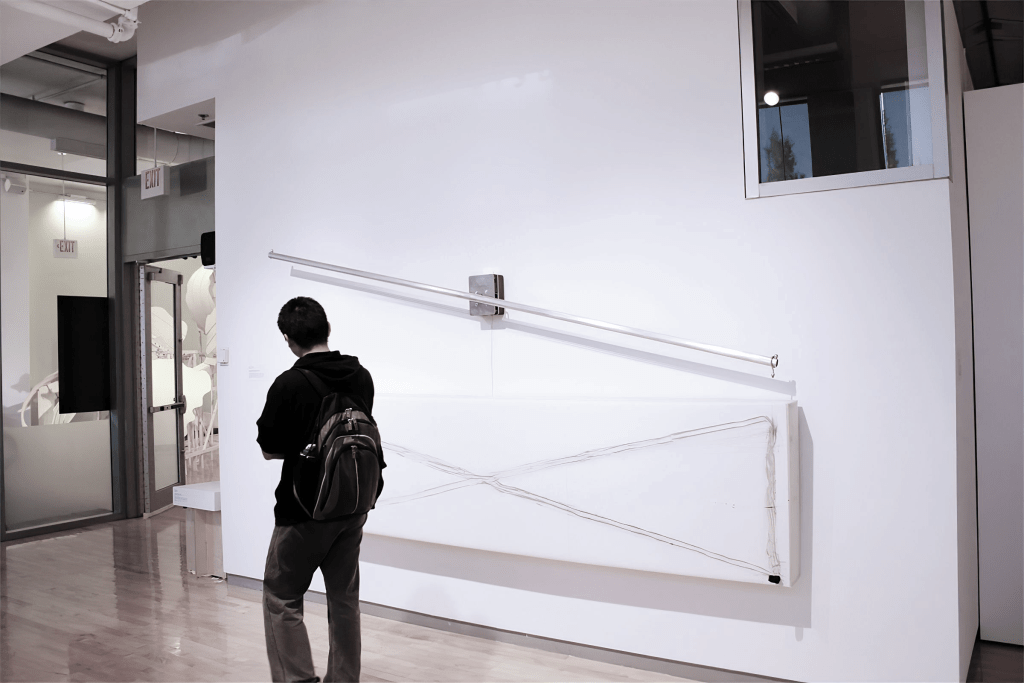

Artists and scientists possess a captivating ability: they transform the intangible into something concrete. These domains venture into unexplored territories, unraveling mysteries and bestowing significance. Whether delving into the depths of our physical universe or weaving fictional tales, science and art hold equal value as they uncover truths about existence through tangible expressions that touch us deeply. For me, tangibility represents the act of giving shape to unspoken phenomena. Information permeates our surroundings, and with the aid of technology, we can begin to unveil these currents and make them palpable. Early in my career, I crafted the sculpture “Time and Tide” as a meditation on this concept.

Time and Tide is a slow-moving, kinetic sculpture, harmonizing with the ebb and flow of the local ocean tides. Picture a long, graceful metal tube delicately swaying back and forth, reminiscent of a majestic clock hand. Suspended from the tube, a hook latches onto a string, delicately holding a lump of charcoal at its end. As the tube reaches the peak of high tide, the hook effortlessly disengages due to loss of friction, gracefully gliding down to the other side. This endless cycle repeats itself, intricately intertwined with the rhythm of the shifting tides. As each sequence unfolds, the charcoal leaves captivating marks on a canvas thoughtfully mounted beneath the art piece. Over time, an evocative infinity symbol emerges, a poignant tribute to the undeniable passage of time.

Nature is an abundant source of data. As our computerized world has brought new insights into the natural world, so-called “big data” has been likened to a giant eye that renders the invisible visible. But raw data alone is just a string of bits. It requires a meaningful expression to become tangible [3]. In the artwork Two Rivers, I sought to use the expression of live data to imagine our relationship to a natural space–in this case the Providence River.

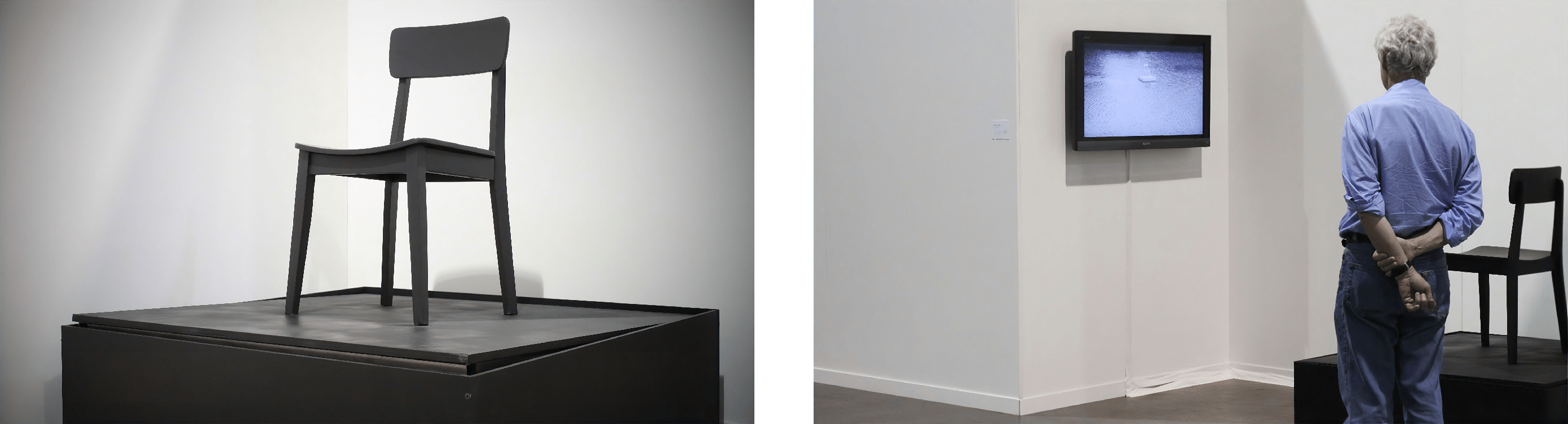

Two Rivers is an experiential kinetic sculpture driven by data. It consists of two identical chairs placed on platforms – one white, gracefully floating on the Providence river, and the other black, situated in an adjacent gallery. The river-based platform employs solar panels and an inertial measurement unit to perceive its natural movement in the tidal river. This motion data, in conjunction with a live camera feed, is then transmitted over the internet to the indoor platform. Inside, the black chair endeavors to faithfully replicate the sensations experienced by its river counterpart. Spectators are warmly welcomed to sit in the black chair, immersing themselves in its captivating movements while simultaneously watching live footage from its location. They may choose between a perspective cam, discreetly positioned behind the seat, or a shore cam for a more panoramic view.

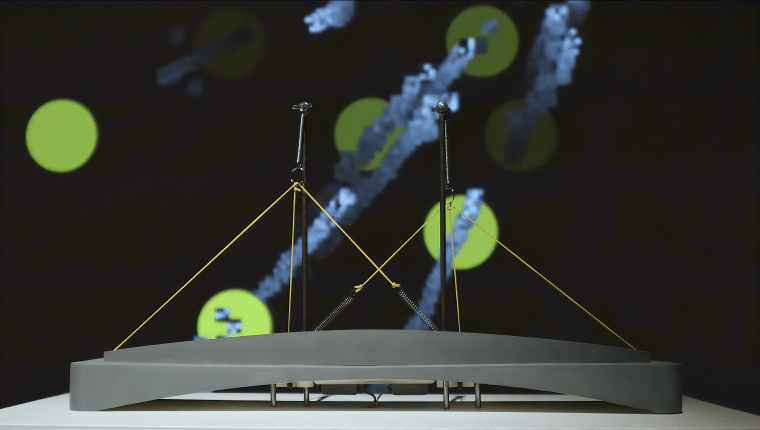

Overflow is another example of data-driven art. This captivating installation combines the worlds of kinetic sculpture and generative sound to create a mesmerizing experience. By utilizing real-time traffic cameras monitoring the bustling Sunshine Skyway Bridge, Overflow interprets footage of traffic flow through custom software. The result is a dynamic soundscape that mimics the stringed instrument in a truly unique way, paying homage to the very bridge it observes. The tension in the strings is meticulously adjusted by robotic mechanisms, responding to the ever-changing traffic patterns, creating a suspended moment where time and space intertwine. Through this artistic expression, Overflow beautifully captures the symbiotic relationship between people and the places they inhabit, much like the Skyway Bridge itself.

Reflecting on Horishi’s experience with the classical scientific instruments, and his successive research on “tangible bits”, we find valuable insight regarding the need to translate data into tangible forms in our digital era. This concept is not only relevant to the scientific field of human-computer interaction (HCI), but also for artists to consider as a compelling creative framework to navigate the digital age [4]. Both artists and scientists possess a captivating ability: transforming the intangible into the concrete. In the 21st century, where data reigns as the new material, artists serve as sense-makers, intuitively connecting minds, hands, and materials. Through fusing art, science, and technology, artists can translate these data into immersive experiences that make the intangible tangible. The artworks shared above aim to express this synergy and demonstrate the boundless possibilities that emerge from this convergence.

References

- Hiroshi Ishii and Brygg Ullmer. 1997. Tangible bits: towards seamless interfaces between people, bits and atoms. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGCHI Conference on Human factors in computing systems (CHI ’97). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 234–241. https://doi.org/10.1145/258549.258715

- Arris, J.C. 2010. Galileo Galilei: Scientist and Artist. Arch Gen Psychiatry 67, no. 8 (August 1): 770-771. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.95.

- Mansion, M. 2011. Natural Fantasy. Rhode Island School of Design. https://bit.ly/thesis-mansion-mikhail

- Grünberger, C. 2022. The Age of Data: Embracing Algorithms in Art & Design. Niggli. [Hardcover].