September 11, 2020 | By Robin O’Dell

Celebrating Herb Snitzer

A Photographic Legacy

Through November

at The Studio@620

Through October 18

at the Dunedin Fine Art Center

Online through December

at the Lumiere Gallery, Atlanta

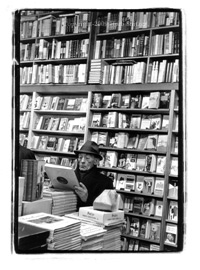

Herb Snitzer has spent a long and storied lifetime photographing his passions. The child of Jewish immigrants forced out of the Ukraine, he connected to social justice issues from an early age.

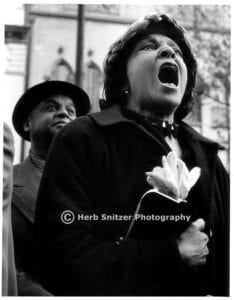

After serving in the military and graduating from the Philadelphia College of Art, he lived in New York City from 1957 to 1964 while pivotal civil rights demonstrations and legislation were taking place. There, he photographed for LIFE, Look, The Saturday Evening Post, Fortune, TIME and the New York Times.

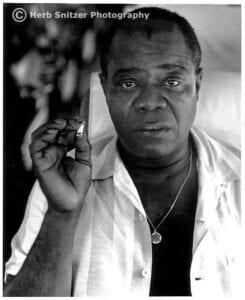

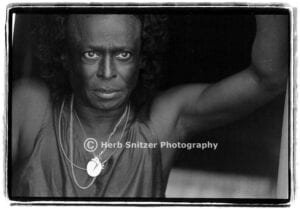

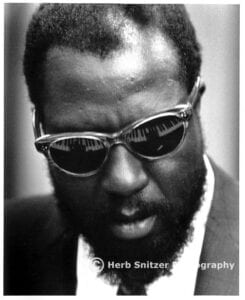

He worked as a photographer and editor for the music magazine Metronome, which gave him the opportunity to photograph and befriend many of the greatest jazz musicians of the time including Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Nina Simone and Sarah Vaughan.

While those photographs remain iconic, they were really just a springboard to the half century of photography and activism that followed. Snitzer co-founded and served as headmaster at a progressive school in the Adirondacks, worked for the famed film and camera company Polaroid, published numerous books and continuously photographed street demonstrations, civil rights gatherings and gay pride parades.

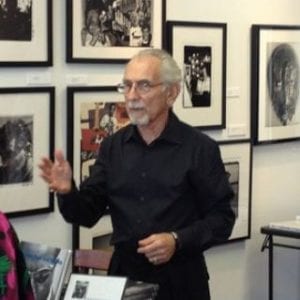

A kind and gentle man, Snitzer turns 88 in November. Recently diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, his output has slowed, yet his commitment to equality for all people and his passion for beauty remains as strong as ever.

Three exhibitions of Herb Snitzer’s work are currently underway

- The Dunedin Fine Art Center is featuring Herb and his artist wife, Carol Dameron, in Between Us, an exhibition celebrating creative partners, through October 18. . . dfac.org/exhibit/between-us

- The Studio@620 is presenting a series of exhibitions. This month, Visions of Social Justice; Images of Life and Strife. In October, Homage to an Influencer: A Curated Group Exhibition. And in November, All That Visual Jazz. . . thestudioat620.org/events/celebrating-herb-snitzer-a-photographic-legacy

- An online exhibition at the Lumiere Gallery in Atlanta focuses on Snitzer’s jazz work through December. . . lumieregallery.net/201/herb-snitzer

In 2018, Curator Robin O’Dell interviewed Herb Snitzer at his home in south St. Petersburg, but that conversation was never published. A follow-up interview took place in August 2020. Text has been edited for brevity and clarity.

2018 Conversation with Herb Snitzer

Robin: What first inspired you to photograph?

Herb: The world. The events of the world, because I really ended up being a documentary photographer.

Robin: If you were starting off now, do you think you would be photographing different things? You obviously became famous for these jazz photographs in New York in the ‘50s. If you were just starting out now, do you think your career would have taken a whole different track?

Herb: I don’t think so. I think I would still be interested in humanity, decency, equality and fair play – and how you can translate that into photographs.

Robin: That’s beautiful.

Herb: I am sometimes drawn to the dramatic, to the theatrical. I love what I have done with the people in the theater world. It was a really joy to meet and talk to Bette Davis. Who would have thought as a ten-year-old that I would be speaking with such a glorious figure…Tennessee Williams… Ossie Davis.

I have a story… because most people, when they ask me, what episode did you miss as a photographer? I tell them February 23, 1968, I was standing backstage at Carnegie Hall with Martin Luther King (Jr.), James Baldwin, Ossie Davis, and me – and I didn’t have a camera.

Robin: Talk about a missed opportunity!

Herb: That’s what I am saying.

It was intermission. We were backstage. If you paid an extra 50 dollars or so, you were able to hobnob with the important folk, and Martin Luther King was certainly the important man of the day. There we were, Martin Luther King, Ossie Davis – and little ole me with no camera.

Robin: Your work has always been involved with the struggle for social justice, for over half a century. What do you think about what’s going on right now (2018) and how do you think it has affected your work?

Herb: I think it’s great. I think that the push for equality and social justice is advancing. I know a lot of people are complaining that it’s not changing fast enough. Well, you know, you are in it for the long haul. And it’s not something you do for a week and give it up and do something else.

I also have an aesthetic side. I will photograph anything that I think is wonderful to photograph. Sometimes it’s social justice, and other times it’s not. I feel I have a balance between the two.

Robin: Other than social justice, what are some of your favorite topics?

Herb: Show biz and theater. I found out I was pretty good at it. I have continued that for all these years.

Now, there was a hiatus of about 15-18 years. I was involved with free school education and was offered…. most people don’t know this… I was offered a position with Cornell Capa as Director of Education at ICP [International Center of Photography] when it was first forming. He was looking for people to work with, and I knew Cornell for a quite a number of years before. So, we had worked it out. But when he told me how much he could pay, I couldn’t live in New York for that amount. So, I didn’t take the job.

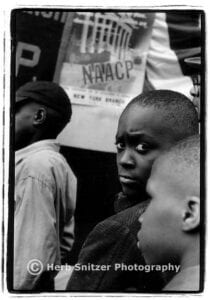

In retrospect, would I be better off working within the photographic world, meeting those major collectors, those major gallery owners? I don’t think so. I think that kind of world was not for me. So, I continued to make pictures, of the Black culture especially. I have been pretty steady at it.

Now, since I moved to Florida, which is now 25 years, my shooting has diminished but my printing has increased. I’ve started printing again.

Robin: You still shoot in black and white and on film. Are the reasons for that because you like working in the darkroom?

Herb: It’s a wonderful experience. I always treasured it. I always look forward to going in the darkroom. This magical thing happens where you throw some light down on a piece of paper and the next thing you know you have an image. It’s a glorious moment.

Robin: There are aesthetic reasons you like black and white as well?

Herb: Yes. Firstly with digital, the image that’s made is with ink. Whereas with photographic paper the image is made of silver. The end result, there is a completely different sensibility, in running your hand over a silver gelatin print as opposed to an ink print.

Robin: Let’s say you are somewhere taking pictures. Cartier-Bresson talks about the “decisive moment.” How do you decide when to press the shutter? Instinct? Do you think about it anymore?

Herb: It depends who I am photographing and what I am photographing.

If I know that I am photographing Louis Armstrong or Miles Davis, then I know I am making a social comment as well as making an aesthetic comment. I know that up front, because I believe that jazz is a metaphor for freedom. So every time I went out to photograph a jazz musician, I always tried to – if I thought he or she were involved with equality or due process, etc. – then I would try to incorporate that in my image.

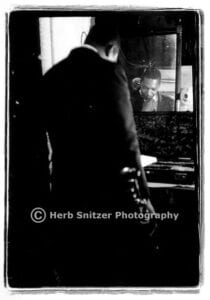

Sometimes it just works, and it has nothing to do with the image itself. Like my photograph of John Coltrane looking in the mirror. I mean, Coltrane himself, yes, but that was just a wonderful aesthetic moment.

So, I try to incorporate my social and political sensibilities with my aesthetic sensibilities.

Robin: If you had not become a photographer, what would you have done?

Herb: Well, I probably would have worked in some capacity of social awareness.

I started college in September 1950, and went in the army in ’53 and that’s when it really started to really take hold. Prior to that I was a painter, and not a very good one.

We are at the beginning of a new way of life. The aesthetic and the morality will pretty much swing with the changes. When I first worked at Polaroid in 1978, a senior vice-president had established a group in Polaroid to determine whether computers were viable.

1978 to today, it’s unbelievable the changes. And 25 years down the road, what’s going to happen? It’s hard to think of it right now, but there’s some young kid in a college dorm (like Zuckerberg) who is going to come up with something that will revolutionize life. And what it is, I don’t know. I won’t be around to find out, which is too bad.

Robin: I know in New York in the ‘50s and throughout your career you’ve been backstage, you’ve been next to artists, you’ve been close to movie stars, you have been smack in the middle of demonstrations – mostly peaceful – but probably not always exactly peaceful. Have you ever had anyone confront you about taking their photograph? Have you ever had anyone get angry?

Herb: Ironically, that happened here in St. Petersburg. There was a demonstration by the Klan. It was 2009, right in front of City Hall. The KKK was out in force, in hoods and everything. One of the Klansmen, he was a young kid, dressed normally. He was a big guy. I was making my photographs. He walked up to me and he thrusts his middle finger up in my face and said something. I was making photos of so many demonstrations, it didn’t even phase me. What was he going to do to me? He wasn’t going to hurt me. There were so many SWAT teams, more than I thought were even possible.

I made this glorious photograph, The Face of Hatred. You used it in Can I Get A Witness. [Snitzer’s 2018 solo exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, St. Petersburg].

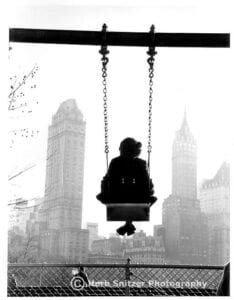

There was this woman, Grace Mayer, who was the curator of photography at the city museum, the Museum of the City of New York. This was 1959, and I had only been in New York two years. This is what knocks me out.

I went to see her because I had done a series on New York, on Central Park specifically, and she set it up where I would have my first museum show at the city museum, which was wonderful. She knew I wanted to meet [Edward] Steichen, who was still alive. By that time she was his assistant at MoMA, so she worked it out where I would meet the wonderful Ed Steichen. And I did. I showed him my portfolio of my early work – and he bought two pictures for 25 dollars each.

Robin: That was 1959. That anyone would pay for photographs at that time! What was he like as a person, Steichen?

Herb: He was very nice. I was very nervous. I was very young. He liked the work. He said, “I like the way you look at people.” I said, “Thanks.” And he said, “Well, we’ll keep this one and this one.”

Robin: Do you remember which ones they were?

Herb: Yeah. One was of a little kid holding a balloon. The other was of a girl coming through darkness. I don’t have the negs, but someone’s going to call for them one of these days.

. . .

Conversation with Herb Snitzer – August 25, 2020

Robin: So much has happened since our last interview in 2018 – with you and also with the world. One of the things I wanted you to talk about, because you have had such a lifetime of activism in social justice, I want to know what you think about what is going on in the world right now with social justice and the Black Lives Matter movement.

Herb: Well, it’s finally come to the surface. For real.

I mean, for a long time it was a lot of people talking, but now there is real change and I can only hope it pushes itself forward. People are energized.

Robin: You were aware and active in the 1950s and 1960s when there were the historic civil rights marches. How does it feel different now?

Herb: On some level, it’s the same, in that there are people committed to social justice and racial equality. In the late ‘50s you had a bunch of people… Black Panthers, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., James Baldwin – it was coming from all sides.

I come at it now with a different kind of view. Because I was living in New York and everything was happening in New York then.

Robin: Is it weird not being able to be out on the streets?

Herb: In photography, there’s a physicality. Very rarely do critics talk about the physicality of the creative process. Werner Bischof, a relatively unknown photographer who influenced me in the same way that Cartier-Bresson influenced me. He was very influential, to the point where… I started a conversation with his widow.

Robin: What kind of camera do you use.

Herb: Basically, a rangefinder camera, Nikon SG. That was my basic camera. Two or three of those and interchangeable lenses. When I was younger, I could put those things around my neck and put myself in situations.

Like paragliding and releasing the cord and free-falling into New York sound – it became a three page spread in LIFE magazine.

We put this harness over me, and clipped it on my chest, clipped it on my thighs. It was attached to a motorboat, and the motorboat started slowly and I was running and the next thing I know my feet are off the ground and I am 150 or 200 feet up.

I made photographs. I had my cameras, and we had prearranged it where I would not have to release any harness because I could not go into the water with the cameras. We circled New York. It was really fun. I was 27.

Then they slowly brought me down and my feet touched the ground. It was terrific. The efficiency of LIFE magazine in those days… three days later it was published. That was unheard of.

Robin: That was film!

Herb: All kinds of stuff like that happened. You know, like with the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. The SS Rotterdam. We were out three miles so that people could gamble.

In those days it was more formal. If you were assigned by LIFE, you might do the job in a tuxedo. It was a fundraiser the American Cancer Society. The Duke and Duchess were on the boat. Governor Rockefeller was on the boat. Assigned by LIFE.

Robin: Have you already put the exhibition at The Studio@620 together?

Herb: We are in the process of putting it together. [Visions of Social Justice: Images of Life and Strife opens September 12.]

I also have a show in Atlanta. 52 pieces of my work. It is up now. It is virtual. It is a wonderful show. Through the end of the year. Lumiere Gallery.

It’s all pretty exciting, three shows going on at the same time.

Robin: You deserve it! Maybe someone will buy some stuff!

Herb: I hope so. The Smithsonian bought my portfolio. [For the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture.]

Robin: If you were to write a book about your life, what would you title it? I know you have made lots of books already, but those are more about your work than your life.

Herb: “Herb Snitzer, a Decent Man.”

Robin: Awwww. You are a decent man.

Herb: … “and A Wonderful Artist.”

Robin: I like that.

It captures everyone’s imagination to think about when you were at Metronome, and going into these small clubs. It was not particularly integrated at that time. And you were everywhere… backstage taking photographs like nobody’s business. Hanging out with these jazz artists.

Herb: I had to gain their trust. The creative world of New York was a multiplicity of colors and backgrounds and so on. We were not affected by the racism. By we, I mean white people, but the Black people, especially Black artists, had a hell of a time.

Robin: Right, there were still segregated bathrooms and restaurants.

Herb: I guess maybe it’s because I didn’t threaten anybody. I wasn’t six foot five and big. I was this little guy with cameras. Talented, although I never considered myself to be an artist. That came later when I realized that I can take that title.

Robin: What changed? How people were treating your work – or did it come from you?

Herb: It came later on. I have all this work now. Maybe it’s only going to show itself 15 years from now. Carol [Herb’s wife] will have opportunities to put the archive somewhere. I want to have it placed sooner rather than later.

Robin: Well, you want to see it!

Herb: I want to see it.

I tell people – it may sound pretentious – we are visual historians. There is a cohesiveness, and that has come out of my political social life. I told my students when I was teaching, make photographs that you believe in.

A.S. Neal [Director that Herb worked with at Summer Hill School] said to me one time, he had just gotten off the phone with a reporter who wanted to come do a story, and Neal said – I’ll paraphrase it – “I waited this long so that I can be loved,” or something to those words… it will all take place as you get older.

I find it is that way with me. People call me on the phone now or come and do an interview, and I think, OK, I guess you had to wait your turn.

Robin: Well, that and you have a huge body of work and that has a certain weight to it.

When you’re first starting out, it is a different part of the journey. But no one can look at your body of work now and not acknowledge the impact you had on history and how you captured that with your own vision of the life that you lived.

Is there anything else you wanted to add? Anything you want people to know about you?

Herb: No, I don’t think so… it’s all in the work.