June 2, 2020 | By Steven Kenny

How Photography Changed the Art World

. . .

The art world was changed forever in 1826 when a man named Joseph Nicéphore Niépce took the world’s first known photograph.

That image was a humble view from his window using a camera obscura. Due to the limits of that nascent technology, the exposure took about eight hours. However, the shockwaves of his invention reverberated long beyond that.

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, View from the Window at La Gras, 1826

Like any new technology, many artists were extremely curious and wanted to test the limits of this young medium. Others looked upon photography’s ability to instantly capture what the eye sees as a threat to the painting establishment. The painterly tradition of representing reality in two dimensions was shaken to its foundation.

Suddenly, many painters of the day were faced with three choices. The first was to continue on the path of faithful representation by direct observation. This practice continues today as can be seen in the profusion of so-called Atelier Schools.

The second option was to reject faithful representation of nature. This ultimately led to the birth of Impressionism.

The third alternative was to accept photography’s new ways of capturing images and integrate these unique attributes into the process of picture-making itself.

By the mid-1800s photography was heavily relied upon by painters — but some wouldn’t openly admit it. In Edouard Manet’s (1832 -1883) case, no photographs of his models were found among his possessions after his death. Did he destroy them? Have a look at his The Dead Christ with Angels (1864) and Olympia (1863).

Edouard Manet, The Dead Christ with Angels, 1864

Edouard Manet, Olympia, 1863

Both figures are lit with that telltale frontal lighting that tends to flatten subjects. As in flash photography, sharp edges are emphasized while subtly modeled surfaces are nearly eliminated.

However, if Manet was working from photographs, instead of using them to make his paintings MORE realistic, he embraced photography’s distortive quirks to create a new stylized form of representation.

Other painters weren’t so secretive. Eugene Delacroix (1798–1863) wrote in his journal, “Truly, if a [painter] of genius should use the [photograph] as it ought to be used, he will raise himself to heights unknown to us.” Exactly what “heights” he was referring to we can’t be sure.

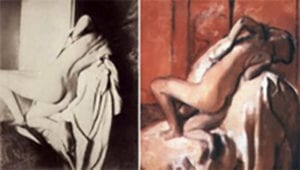

Jean-Léon Gérôme, Phryne revealed before the Areopagus, 1861, with reference photo by Nadar

Critics, too, were aware of, and sometimes sympathetic to, artists’ use of photography. Ernest Chesneau (1833-1890) labelled photography the painter’s “most precious aid.”

More and more artists jumped on the bandwagon as photography became easily accessible.

Edgar Degas (1834-1917)

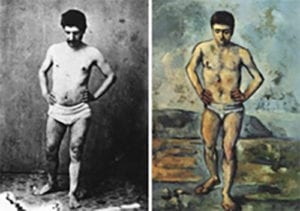

Paul Cezanne (1839-1906)

Anders Zorn (1860-1920)

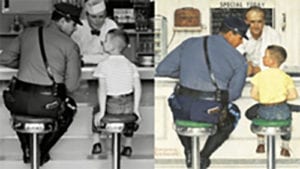

Fast forward to the mid-20th Century and photo use was in full swing, especially among illustrators.

Norman Rockwell (1894-1978)

Today, right here in St Petersburg, there are wonderful examples of painters who have employed photographic reference in their work. Many of the works in the Salvador Dalí Museum were composed using source photos commissioned by the artist himself or with images taken from magazines.

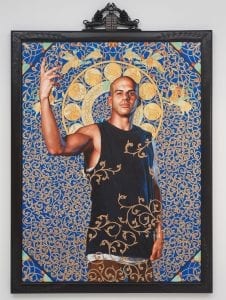

At the Museum of Fine Arts we have the grand portrait by Kehinde Wiley called Leviathan Zodiac (2011), one of a series of paintings called The World Stage: Israel. Wiley traveled to Israel to find and photograph the models portrayed in the paintings.

Video still of Wiley’s photo shoot for Leviathan Zodiac.

Kehinde Wiley, Leviathan Zodiac (2011)

Today, photography is woven into our everyday lives. Anyone who carries a cellphone takes for granted the fact that a camera is always at their fingertips. Technology has advanced exponentially and the ease of photo editing we enjoy today could not have been imagined a generation ago.

I hesitate to say that photography has made us all artists. But it certainly has cracked opened the door to creativity and allowed us all a peek inside.