Words and Photos by Yuly Restrepo

. . .

Through December 26

Florida Holocaust Museum

Details here

. . .

The Florida Holocaust Museum’s website declares that its exhibition Her Response: Women Artists from the Permanent Collection is meant to serve as a dialogue that invokes varied aspects of the Holocaust. The exhibit feels like a call to action.

Located on the second floor of the museum, it presents artwork in a variety of mediums including painting, photography and installation. Artists’ perspectives on the subject look to the past, present and future – exploring both the artists’ personal relationship with the Holocaust and their perceptions of our society’s relationship with it.

I walked through the exhibit with one of my best friends, but as we entered the space, without much discussion, we fell into a rhythm in which each of us looked at the artwork separately, with very few words exchanged. Like the rest of the museum, this space immediately invites contemplation, introspection and reflection.

When we discussed our impressions afterward, we both agreed that in its goal of incentivizing dialogue about the Holocaust and its repercussions into the future, the exhibit was successful.

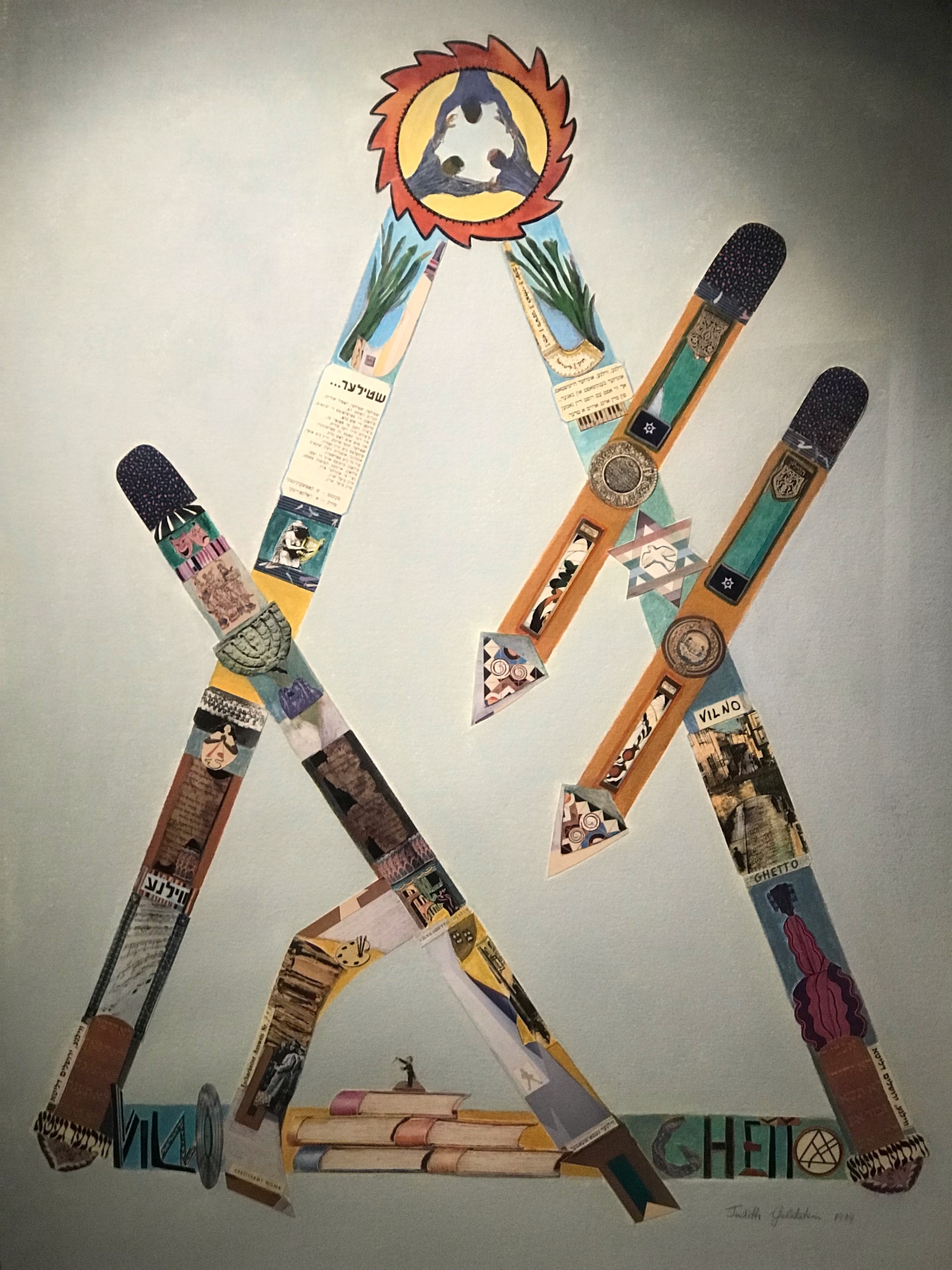

One of the artworks whose power we immediately agreed on was Judith Goldstein’s collage, Vilna Ghetto. It is seemingly one of the least intricate works in the exhibit, in the sense that it depicts a simply stylized version of the letters vav and gimmel of the Hebrew alphabet – but its great pull lies in the work’s evocation of the imagery the artist herself recalls as a survivor of life in the ghetto, and how Jews who lived within its confines endeavored to keep their cultural heritage alive.

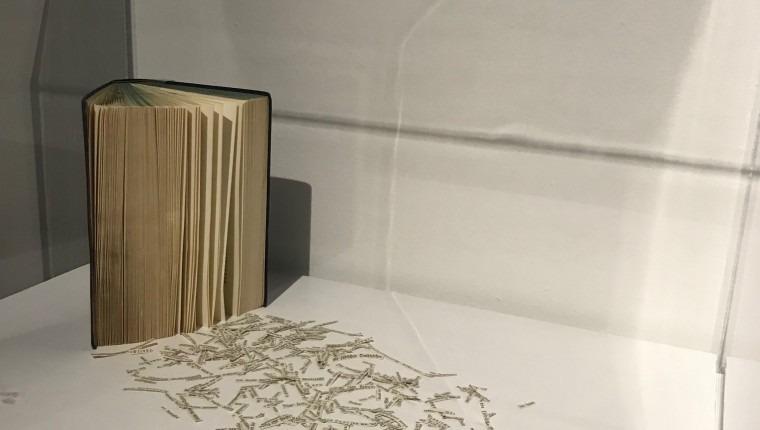

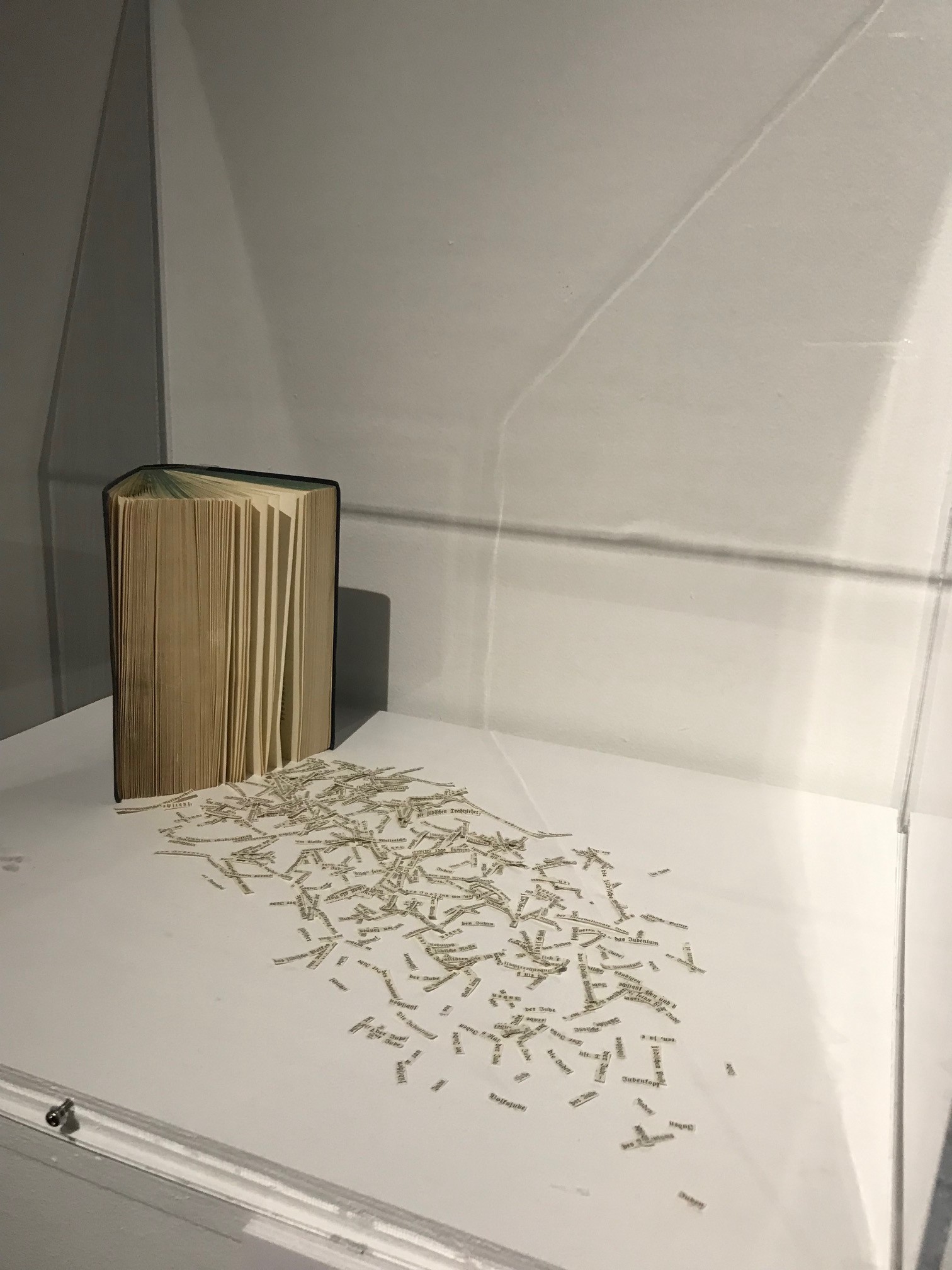

I was similarly struck by the work of Diane Chen Koch-Weser, whose Exodus presents an original copy of Hitler’s Mein Kampf from which all references to Jews have been carefully and methodically excised. The cut words, about 400 overall, spill out of the book, forcing visitors to confront the work’s pervasive antisemitism.

It’s a freeing after the fact, and one that inevitably brings to mind all those who died and were imprisoned under Hitler’s rule. Another of Chen Koch-Wesser’s works is the series Reality Check, where the artist transformed collectible plates that originally depicted idealized American scenes and portraits from the past with ceramic transfers of symbols that re-cast the plates’ subjects as Jews targeted by the Holocaust. The additions to the original images strip them of their idealism, denying us the luxury of being indifferent to the horror.

Among my favorites are also Shirley Shulman’s Wrappings, a series of sculptures made of wood, burlap and other materials, which while leaving some room for interpretation, clearly depict figures that can be easily be anthropomorphized as representations of grief, pleading and oppression.

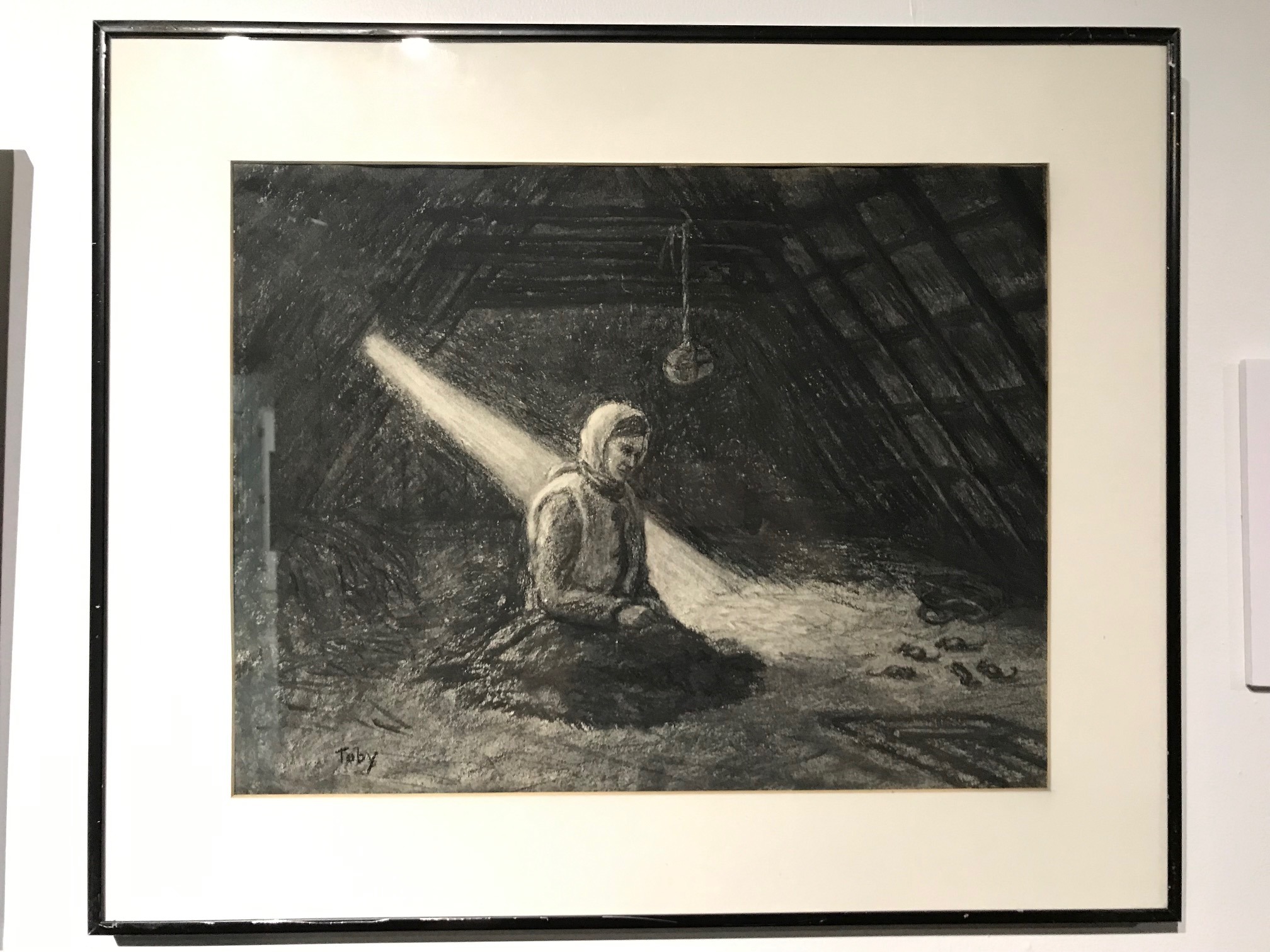

Similarly, Toby Knobel Fluek’s small-scale drawings and paintings present memories of her life before, during and after Nazi occupation. One such work is Hiding in the Attic, a charcoal drawing in which the artist perfectly captures the last days of the war, a time she spent in hiding with no one but mice and the hope of liberation for company. In the drawing, that hope appears as a small window to the outside world.

Without a doubt, the work that caused the most debate between my friend and myself was that of Edith Altman. In her series, Reclaiming the Symbol, Altman presents installations and collages that invite us to reckon with some of the most powerful symbols that were used in the Holocaust to separate the Jews and illustrate the consolidated power of the Nazis.

One half of the room holds an installation with two very large swastikas, one gold and counterclockwise, and one black and clockwise presented as the shadow of the first. The first represents this symbol’s original form and meaning, which in Sanskrit is “well being.” The second represents it as it was stolen by Hitler. Surrounding the installation are other representations of the swastika throughout history.

In her work, Altman “encourages the viewer to redefine their relationship with symbols used by the Third Reich.” In our discussion, my friend and I debated whether this is possible, particularly for a Jewish person. Nazi power was so totalizing and so utterly destructive and widespread, its symbols so unashamedly deployed against Jews, that even almost a century since the Holocaust, these images are instantly associated with the murders of millions of people, with imprisonment, starvation, experiments and dehumanization. What would it take to strip these symbols of their destructive meaning?

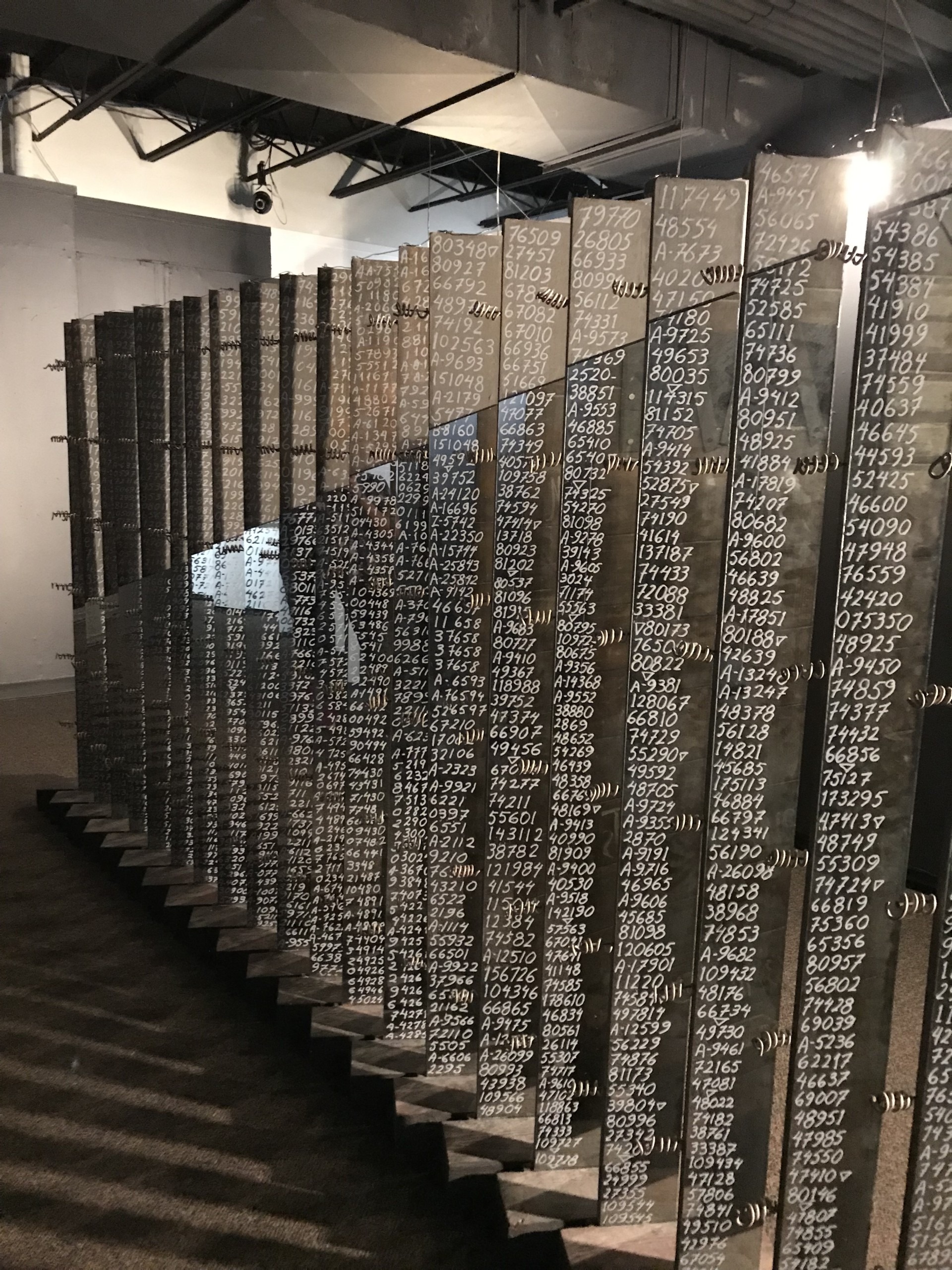

The work that had the strongest impact on both of us is Pearl Hirshfield’s Shadows of Auschwitz, a stunning installation of long, narrow mirrors inscribed with the numbers of tattoos sent to the artist by Holocaust survivors, as well as “numbers from 1942-43 ledgers retrieved from Auschwitz.”

When looking at these numbers, which decrease or increase on each mirror, depending on the direction the viewer is moving, one must also look at oneself, and think about the inescapable fact that behind each number was a person with an individual story and a unique way of experiencing the horror of the Holocaust.

This horror is compounded when looking at the backside of the mirrors, which in a row form the picture of a train car much like those used to transport Jews to deathcamps.

The creative work the Holocaust has inspired in all of these artists reminds us that this history is not too distant – and that facing it is more than a collective memory exercise. It is a reckoning with how our past informs our present, and how history is always alive, even when humans insist on killing each other.

. . .

You can explore the work of

the Florida Holocaust Museum here