In 1875 Tiffany was renting space at Thill’s Glasshouse in Brooklyn and began to study stained and tinted glass in more detail, while trying to replicate some of the colors he had first been intrigued by while traveling through Europe and North Africa, in the 1860’s. He later talked about this time, saying, ‘I then perceived that the glass used for claret bottles and preserve jars was richer, finer, and had a more beautiful quality in color variations than any glass I could buy. To unravel this puzzle, I took up chemistry and built furnaces.’

Those furnaces were built in 1878 and Tiffany brought in a skilled glass-blower from Venice to conduct the experiments. The furnaces were destroyed by fire, twice, and the glass-blower resigned, but around this time two ecclesiastical commissions gave Tiffany some early practice. Windows for churches proved to be an essential part of Tiffany’s trade; the nation’s economic prosperity had given rise to a spate of church building and improvement, and by the mid 1880’s Tiffany had opened a specialized ecclesiastical department.

Patents Filed:

Between 1880 and 1881 Tiffany filed three patents for glass-making. One patent was for creating iridescent glass tesserae (small squares or tiled used in mosaics), another that involved superimposing stained glass panels to induce opalescence, and a third that detailed the use of metallic oxides to produce iredescence on window glass.

The techniques outlined produced a type of glass, with iridescent and metallic lusters, that Tiffany continued to develop for many years, and which he eventually called Favrile. (It was initially called Fabrile, from the Latin root for ‘handmade’, or ‘craft’ – but the name was later changed to Favrile and trademarked in 1894.)

Opalescent Glass:

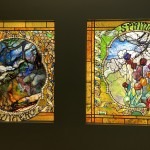

The glass made at Tiffany Studios was called opalescent glass. It was radically different from pot metal, a type of glass commonly used in Tiffany’s era. Pot metal was uniformly colored, translucent, and regular in every way. Craftspeople making pot metal windows often painted them with enamels—a glass paste—to create form and visual effects.

By contrast, opalescent glass was fabulously varied in color and texture—even within a single piece of glass. By careful selection, Tiffany could use his glass to mimic foliage, fabric, water, or a sunlit horizon. Tiffany, in a sense, was painting with glass, as opposed to painting on glass.

Next week I will complete my narrative on Tiffany’s glassmaking techniques by discussing the highly talented designers and craftspeople who were able to translate Tiffany’s vision into some of the most memorable glass creations of our time, and also, some of the criticism he received for his representation of his female employees.

TIP OF THE WEEK:

Has your creative process hit a block? Maybe it’s time to experiment with different materials and techniques?

Use Tiffany’s drive to replicate the opalescent effect he could create with oil paints into glass creations and take a trip to a local art shop to pick up some new materials and surfaces to experiment with.

Be well,

Eileen 🙂

(20+) Eileen Marquez | Facebook