By Tom Winchester

. . .

Women’s Work

A Survey of Female Photographers

. . .

Through September 11

Museum of Fine Arts St. Pete

Details here

. . .

Women’s Work: A Survey of Female Photographers, emphasizes the early contributions of women in photography. For this exhibition, Curator of Photography at the MFA Jane L. Aspinwall Ph.D., brings together photographs from the museum’s permanent collection that serve to rewrite the artform’s male-dominated history. The exhibition includes artworks created by many of photography’s most notable women, as well as several whom viewers will be meeting for the first time.

Unlike traditional media such as drawing, painting, sculpture and dance, whose histories date so far back that they have irretrievably forgotten women, photography has been around for less than 200 years. While often inexcusably overlooked, the contributions of women in the history of photography are undeniable. We literally have photographic proof of it.

. . .

. . .

The fact that Aspinwall can curate an entire exhibition of women photographers from the museum’s permanent collection asserts the influence of women in the history of photography. Their influence comes into full focus when you consider that some of the photographs in Women’s Work were created when photography was first invented.

The MFA has been collecting photography by women since the early ‘70s, and Aspinwall credits a former assistant director of the museum for its substantial collection of photographs created by women.

The exhibition is arranged chronologically and begins in the earliest days of photography, during the mid-19th century. Aspinwall says, “The earliest piece is one of our Julia Margaret Cameron, who, some argue, was making the first art photographs.

“Like a lot of the earliest women photographers, she came to photography very late in life, after she had raised her children. She had received a camera as a present from one of her kids and was really smitten.”

. . .

. . .

She points out that Cameron was an artist, as is evident by her use of painterly soft focus and representations from art history in her work. “A lot of the early women photographers had to focus on themes of children, family, and religious themes. This one is of the Madonna and Child. From the very beginning — from daguerreotypes — there were incredibly artistic photographs being made. I think those are completely written out of the history.”

One grouping of photographs by Gertrude Käsebier, who was making photographs during the turn of the 20th century, was gifted to the MFA by Käsebier’s granddaughter in 1974. Käsebier, like Cameron, came to photography after raising a family. She served as a mentor for younger women photographers, four of whom are on view in Women’s Work. These women led successful careers during the feminist movement of the 1920s.

. . .

. . .

Aspinwall says, “With the suffrage movement, and women becoming more educated, and choosing not to get married, they were able to choose careers. Photography was one that was very fitting for women. These are four examples of the traditional portraiture work from some of the biggest names. They were portrait photographers, and many of them exhibited at camera clubs.”

The most magical piece in the exhibition is an autochrome by Olive Edis. It has the ghostly reflections of a daguerreotype, the muted chromatic scale of a hand-coloring, is about the size of an eight-by-ten, and folds upward and outward like a pop-up book. One of the first known color photographic processes, Edis was not only an expert of the autochrome, but also held its patent.

. . .

. . .

In the section of the exhibition labeled The New Vision, the style of photography shifts to feature abstract artworks. A photograph by Ilse Bing shows a banal moment with two cast-iron chairs sitting empty at a Parisian café. Its subject matter, from today’s lens, seems very contemporary, and the way it’s printed accentuates the negative spaces created by the chair’s forms. At first glance, it could easily be mistaken for a monochromatic still-life drawing.

Aspinwall says, “Bing was one of the first to use that quick, tiny, 35-millimeter camera. It really changed what you were able to do because you could move, you could be spontaneous, and you could catch things on the fly. This one is of the Champs-Élysées. It has an unusual vantage point, strange cropping, and there’s no horizon line to anchor the viewer.”

. . .

. . .

Aspinwall incorporates feminism into The New Vision by including photographs the were created in an effort of, as she says, “[R]ecapturing the female body from the male gaze.” It includes Barbara Morgan’s photograph of choreographer Martha Graham, which shows an abstract form created by the selective cropping of Graham’s torso. With no identifiable clues as to whom the image depicts, the photograph focuses on the tension between movement and stillness.

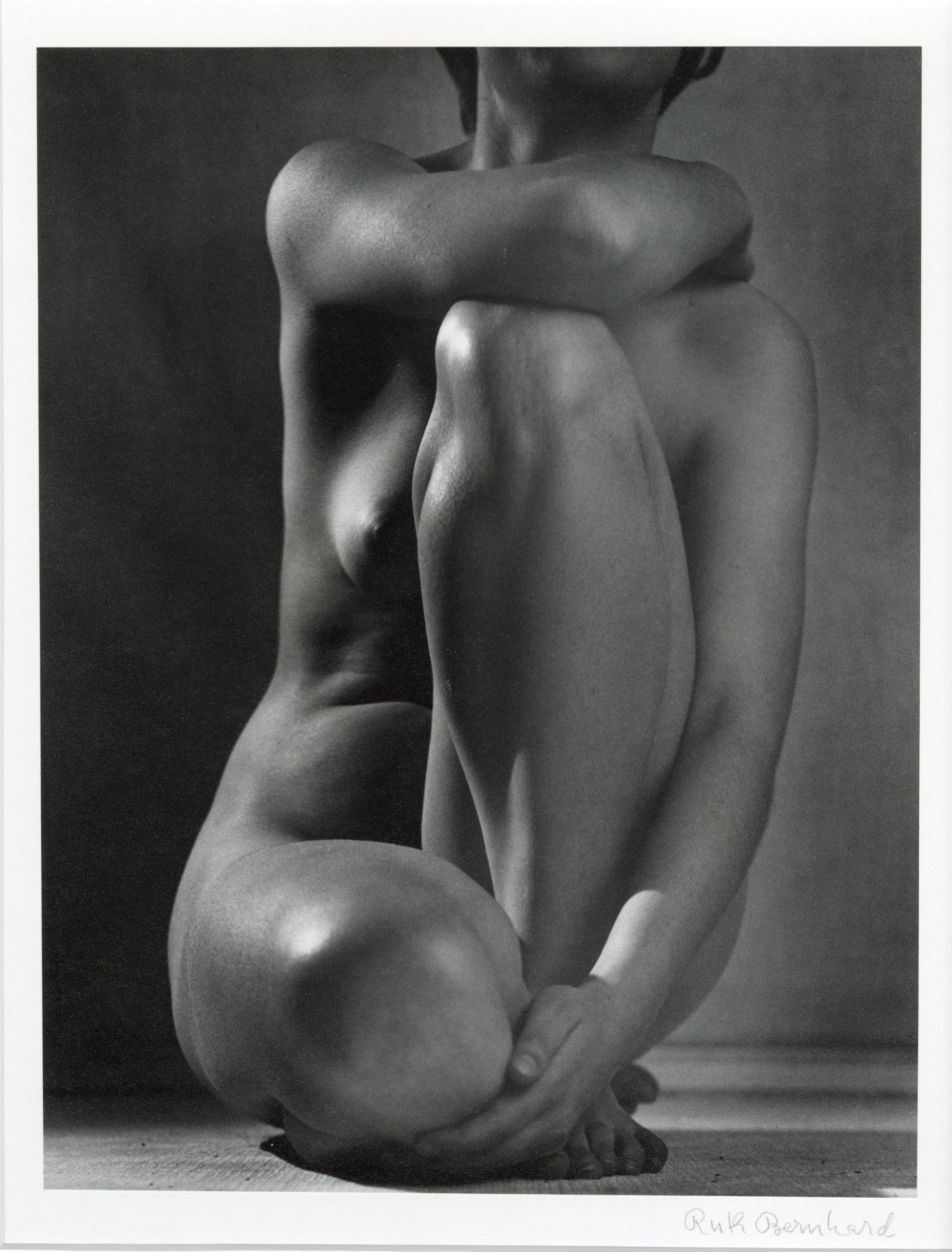

Curated alongside is a photograph by Ruth Bernhard that shows a feminine human form presented in the way many male photographers of the 1930s were photographing nude women. The woman in the photograph is sitting on the floor with her knees at her face, her head tilted away, and her arms snugly intertwined. It’s tightly cropped, and is printed with a wide gradation of grays, which gives it the look of an Edward Weston print. Aspinwall says, “Bernhard is taking a firm very feminist stance against male photographers who were photographing nude women.”

. . .

Aspinwall shares a story about social documentary photographer Marion Post Wolcott, and how Wolcott’s boss’s traditional views at the Farm Security Administration were a hinderance to her. “She was a really beautiful woman,” Aspinwall says, “and her boss, Roy Striker, was very reticent to send her anywhere by herself. So, he sent her on a lot of assignments where she was photographing the face of America. . .”

. . .

. . .

What we see are two photographs depicting upper-middle class America – one of smiling, happy kids at what looks like a daycare center, and the other of tourists, dressed in black, vacationing at Siesta Key with their retro-looking car parked on the white sand of the beach.

Wolcott’s boss, Aspinwall adds, had specific advice for how she should dress while photographing on assignment in Florida. “There are letters between the two of them where, at one point, he’s scolding her for wearing pants. And she’s like, there are mosquitoes. I’m wading through water. I’ve got to have pants.”

. . .

. . .

The most clearly defined thematic shift of the exhibition comes with the photograph by Diane Arbus. The impact of her photograph Girl in a Shiny Dress (1967) mimics the magnitude with which her art has impacted the history of photography.

Arbus’s photographs of the 1960s New York City underworld are practically indiscernible from Nan Goldin’s inner-circle of the 1980s, or Corrine Day’s clique of the 1990s, in that they still look avant-garde. This photograph depicts a young woman in a party dress leaning slightly forward with her hands clasped behind her. She wears heavy make-up with thick eyeliner, and grins melancholically toward the camera.

. . .

. . .

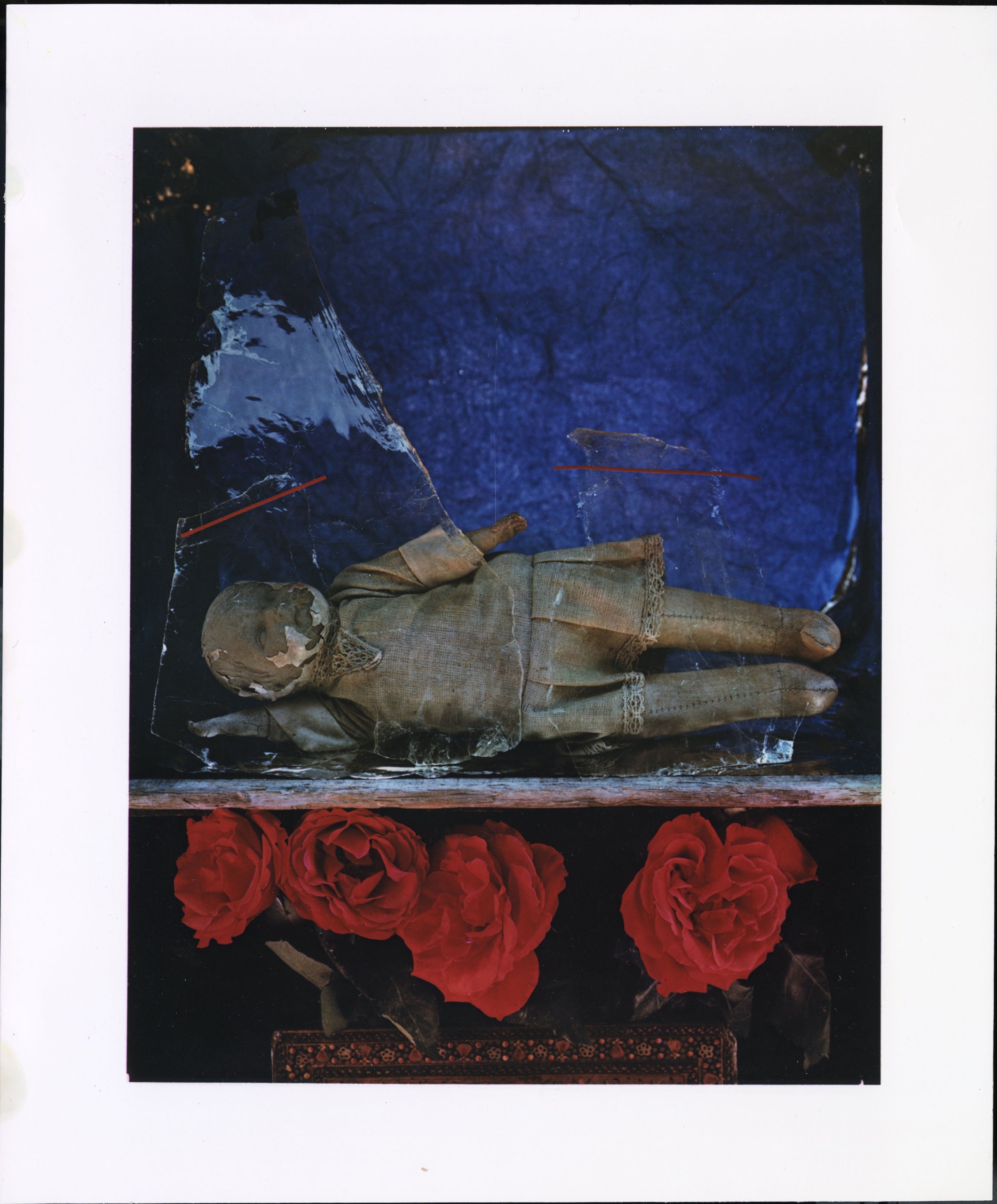

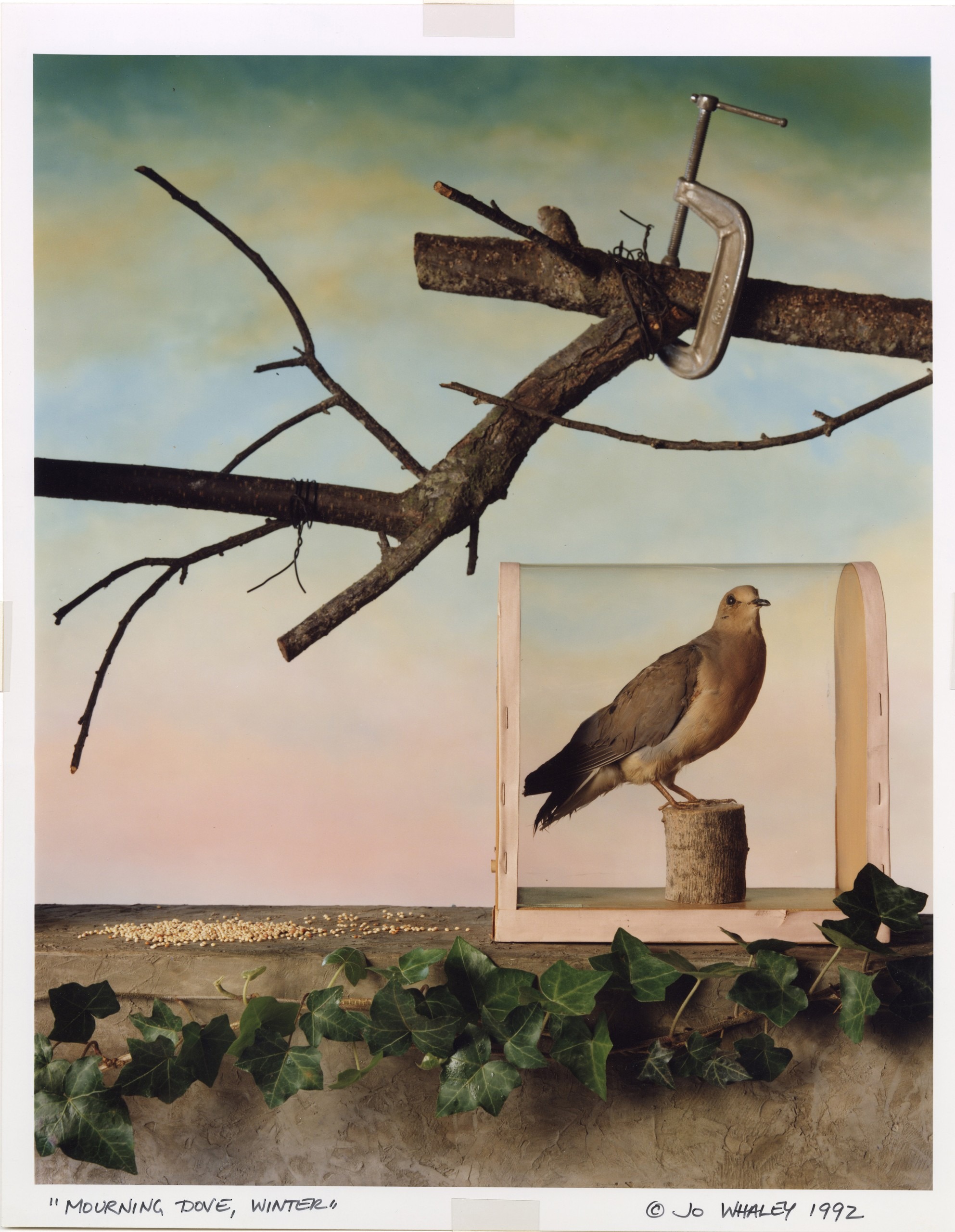

Curated alongside Arbus are color photographs created by Olivia Parker and Jo Whaley. One is a chromogenic print that has that yellowish cast many old color prints obtain over years, and the other is a dye-transfer print that looks as saturated with color as a slide from a carousel. The shift from black-and-white to color photography in this section of Women’s Work signals a new era for the artform – one that looks more like the experience of our era.

The largest photograph in the exhibition is a sepia-toned self-portrait by Fiona Foley titled, Wild Times Call 6 (2001). Aspinwall says, “She’s an indigenous Australian photographer focusing on issues of Native identity. She had a residency in the United States where she borrowed clothing from the local tribe, Seminole, and has positioned herself next to this dugout canoe. Foley is reacting to Edward Curtis, and his photographs of Native Americans at the turn of the 20th century.” By recontextualizing the indigenous identity in a way that references the images made during colonialization, Foley is rewriting history from the perspective of authenticity.

. . .

. . .

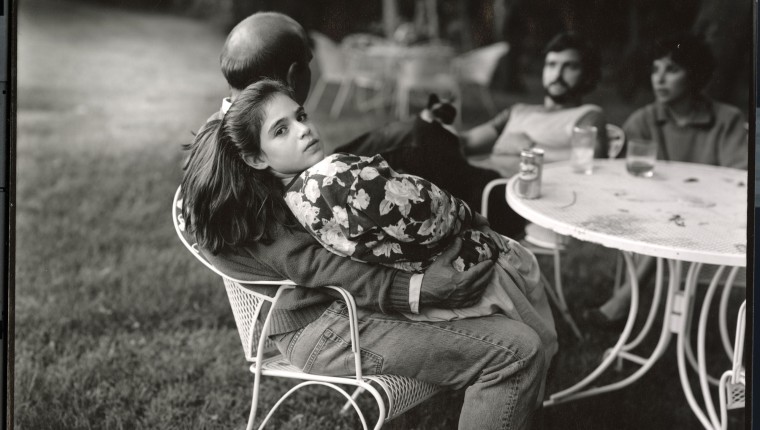

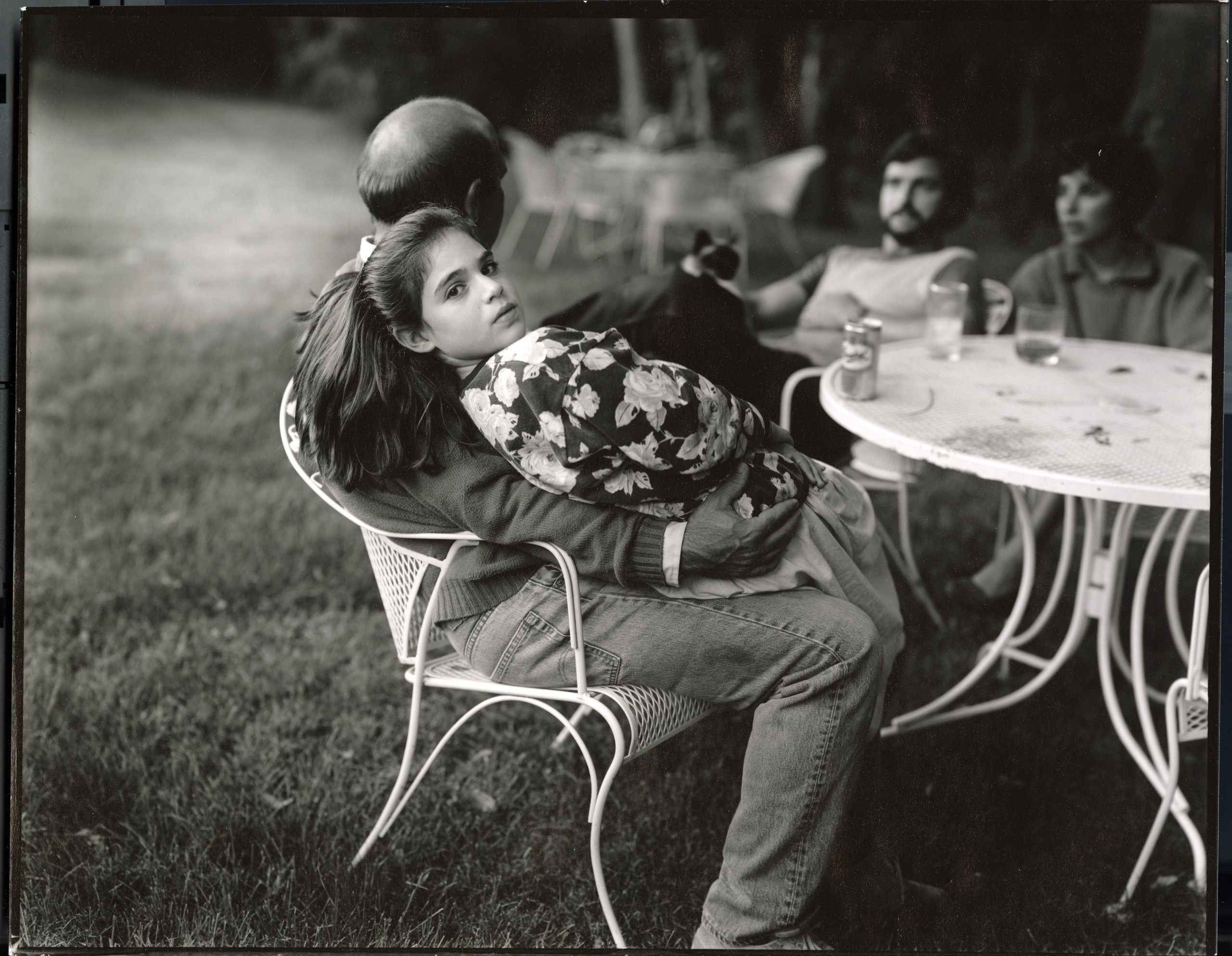

The exhibition comes full circle with Sally Mann, who is known for photographing her children. The show closes with her image Leah and her Father (1985). “It’s from her series At Twelve,” Aspinwall says, “where she photographed 12-year-old girls in this not-quite child, not-quite-adult stage of their lives.” She refers to Mann’s quote about how viewing intimate photographs of young children is the responsibility of the viewer. “These girls exist in an innocent world in which a pose is only a pose. What adults make of that pose may be the issue,” Aspinwall quotes Mann.

Women’s Work further develops our picture of early women photographers, and how they were mothers, businesswomen, suffragettes, as well as artists. “I was trying to really dig into the archive, and pull out some things that haven’t been seen,” Aspinwall says, “I wanted to include the important names, but also women you may never have heard of.”

The exhibition reveals that men weren’t the only pioneers of photography, and that women were creating photographic imagery that was meant to be understood as art from the earliest days.