Through October 22

Dalí Museum, St. Pete

Details here

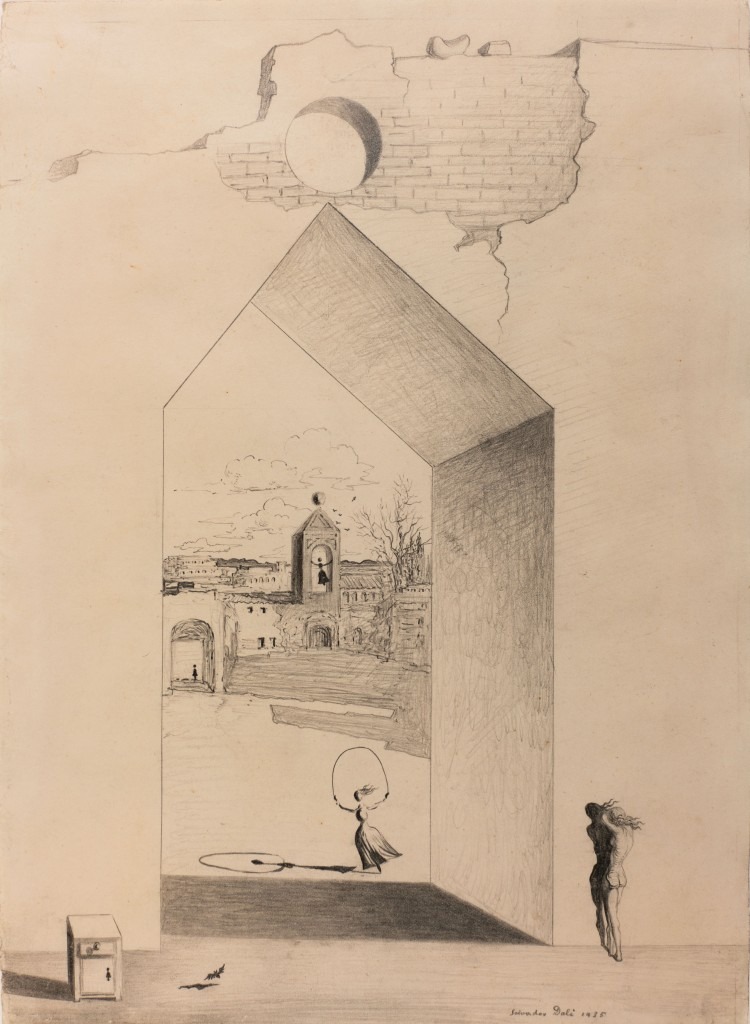

The Dalí Museum’s description of this exhibit – “Approximately 100 works on paper showcase Salvador Dalí’s utilization of various media, including pencil, pen, charcoal, watercolor and gouache, and highlight the artist’s creative process throughout the many phases of his career.”

Salvador Dalí seems to have drawn constantly. His appropriately eccentric book, 50 Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship, focuses mainly on painting, but incorporates drawing advice throughout. It is a source for more drawing examples that enrich our understanding of his philosophy of drawing.

I would say that the display is a cross section of the means of and reasons for drawing. It is interesting to see all the ways that Dalí exemplifies these many facets.

The means would generally be the media listed above. While some may quibble at the inclusion of gouache and watercolor, the use of those media follows the exploratory “whys” of drawing. A number of quotes from Dalí on the walls speak to how he viewed this activity. More than half of these works are on view for the first time in 35 years, due to their fragile nature.

Having been a drawing teacher for about 30 years, I think the most interesting way to view these drawings is to consider them broadly as demonstrating some of the reasons to draw.

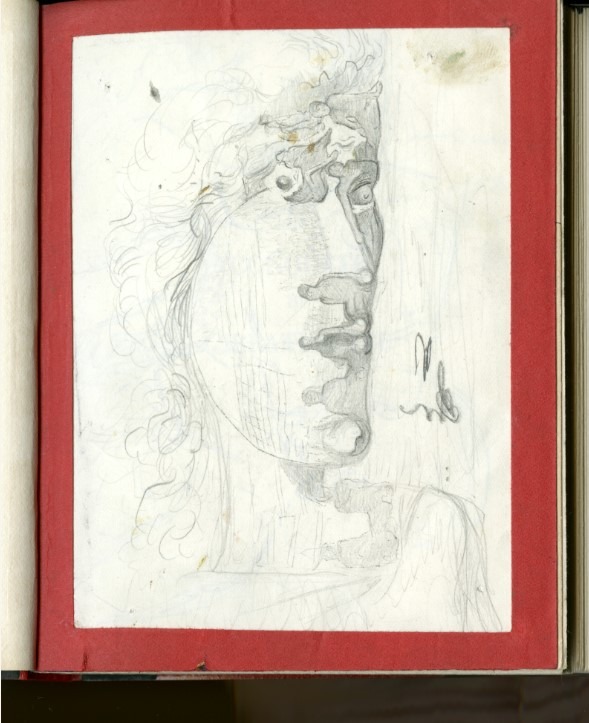

To develop skills

We see Dalí developing technique from an early age. “Remember that the whole lofty morality of your work depends on knowing how to draw,” he says.

We can see his observation and sensitivity in the earliest works such as his pen and ink explorations and landscapes. The drawings that appear to be from his time in the academy demonstrate how well he observes.

“You must begin to draw with a total disregard for what you are representing” touches on the mental exercise required to separate what our mind thinks from what our eye sees. The ability to draw what we see leads us/him to be able to depict what only our minds can see.

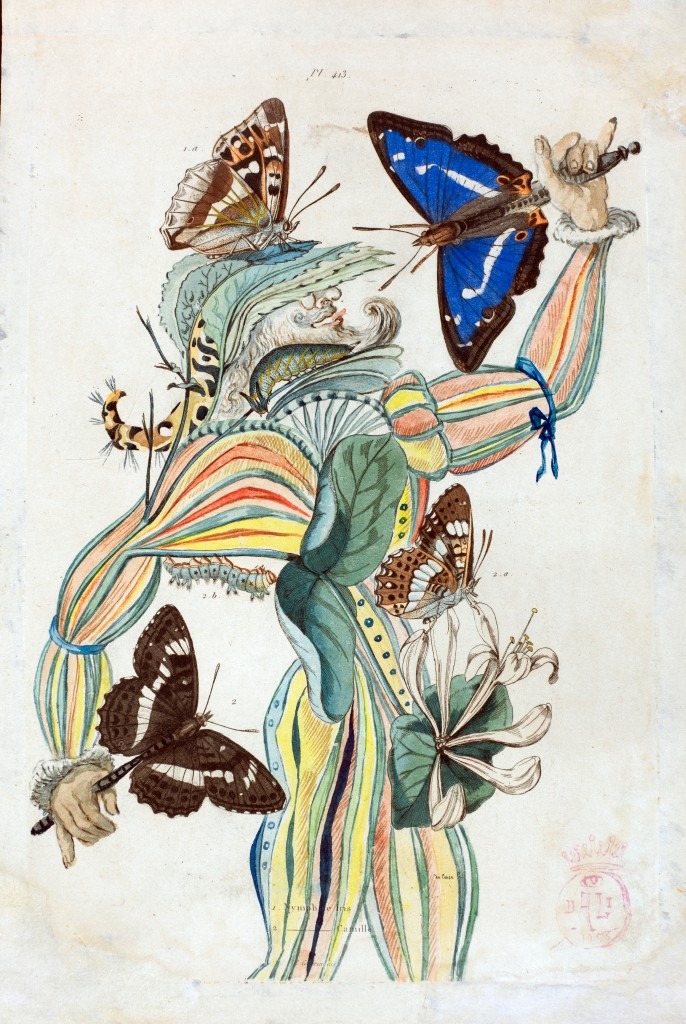

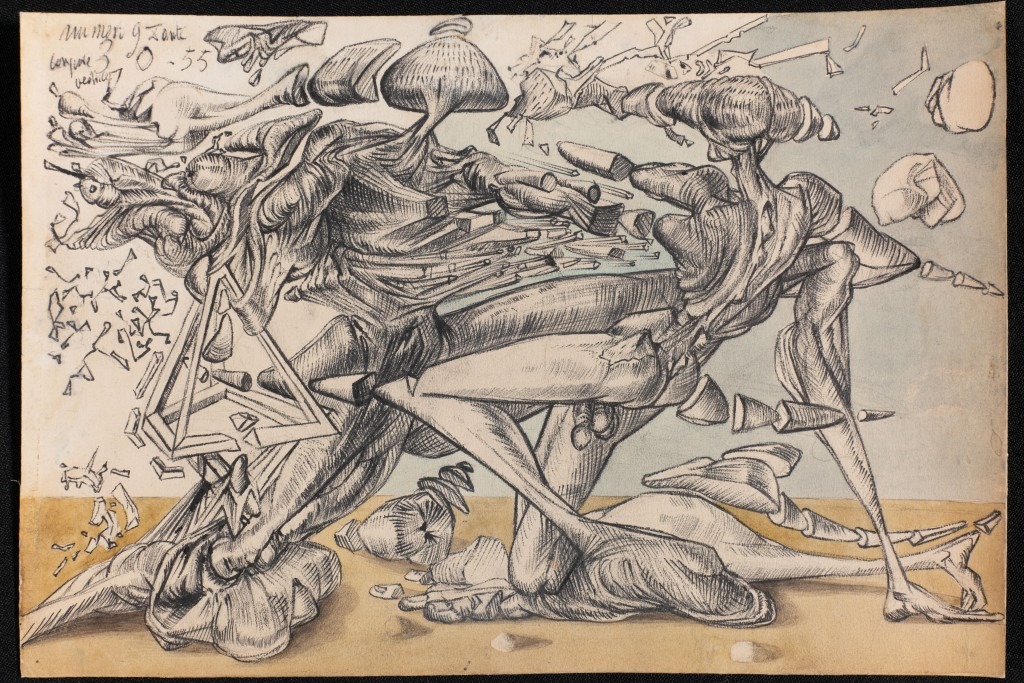

To play, think or imagine

Creative exploration leads to idea development. The many experimentations with Surrealist and Dada approaches – such as finding and developing images from blots or splatters, decalcomania and collage, or seeing something different in found objects – result in strikingly new interpretations and expressions.

For example, Dalí turns Montague Dawson’s lithograph Wind and Sun…The Lightning into The Ship, where he combines a woman with the ship’s sails, to create a metaphorically intriguing image.

To plan

Making preparatory drawings helps one find and strengthen a composition. Examples of this can be seen in Dalí’s study for Disappearing Images (among others) and his exploration of ideas in the “storyboards” for his cinematic projects and ballet costume designs.

Interestingly, where English uses the word draw – possibly in the sense of “pulling” an image – the words for drawing in French and Italian are “dessiner” and “disegnare” respectively, closely related to “design.”

To see or study

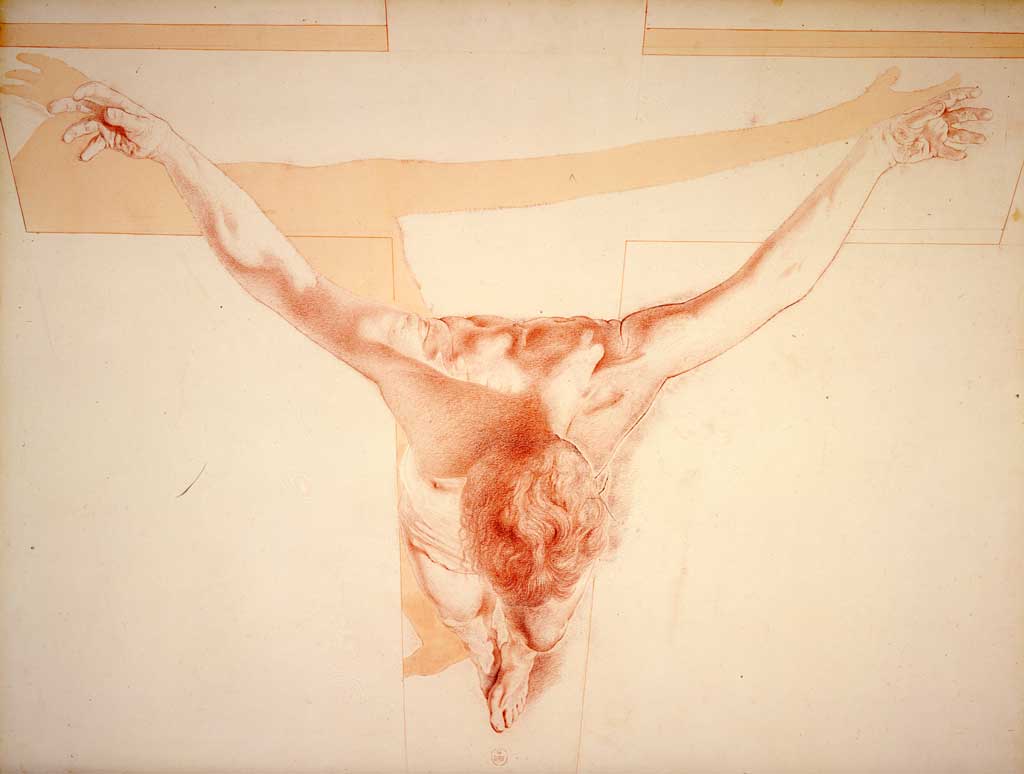

“Drawing is the honesty of the art” can apply to how much Dalí prepared for planned works such as Christ in Perspective, where the details of figure construction and perspective need to be recorded.

To entertain

Riot in a Brothel looks to have been done as much for amusement as for trying on a Matisse-like approach to figures. It is a cartoonish depiction of naked women running and furniture flying, executed in thick and thin undulating lines.

To learn

We can also see Dalí trying on and learning from different art movements in other drawings, such as Reclining Woman, whose geometrically simplified and distorted figure is so Cubist it could be a Picasso.

To illustrate

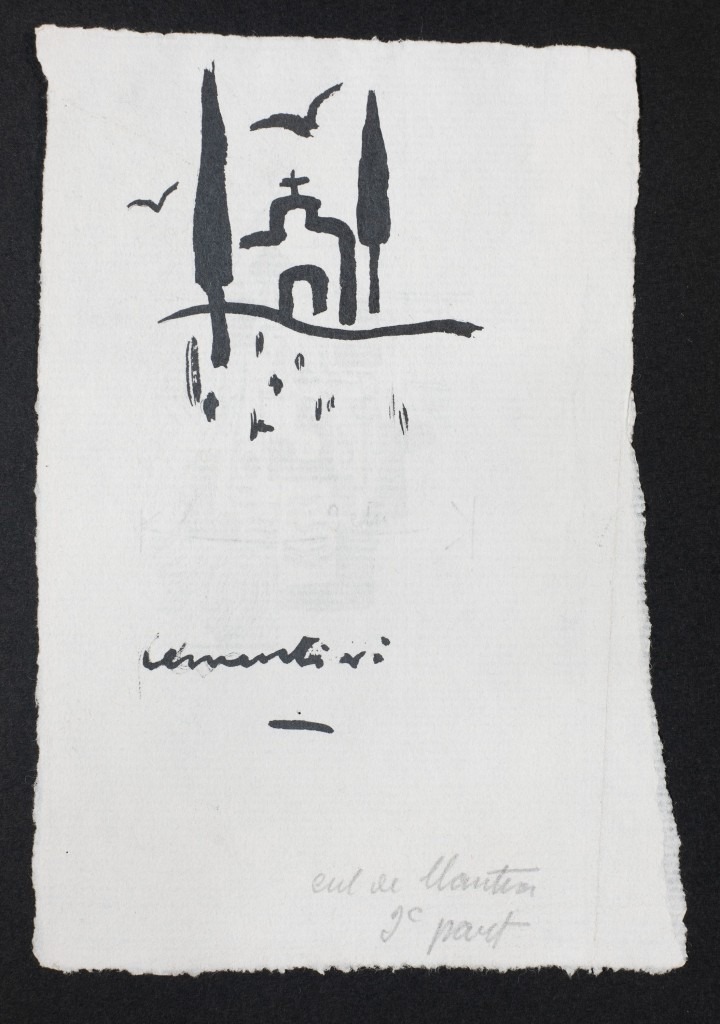

The set of drawings for L’Oncle Vicents combines elements of Cubism and Fauvism that would enrich any story. The flattened spaces and simplified characters give a sense of whimsy to this children’s book.

To explore or process

While we see Dalí experimenting with a number of styles, we can also note his use of recurrent images, such as crutches and the self-portraits inspired by the rock formation Head of Culleró at Cape Creus in Spain, as well as figures with cut-outs, insects, drawers, exaggerated appendages, and many others.

We could imagine that he is examining and analyzing his own experiences and emotions through the repetition of these metaphorical images.

To respond to other forms of art

Ekphrasis is usually written work inspired by something visual, such as Ode on a Grecian Urn by John Keats – but it can go the other way without simply serving as illustration. The concept of Gradiva was inspired by Freud’s analysis of the novel by Wilhelm Jensen. The theme resonated with Dalí in his vision of Gala.

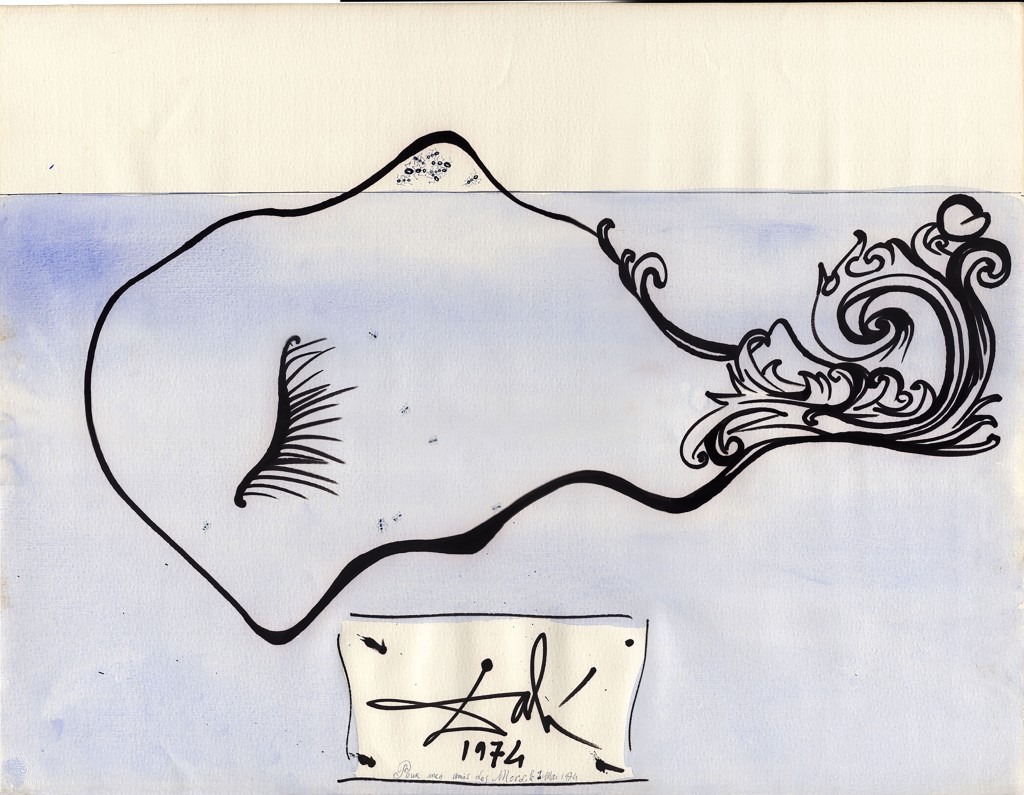

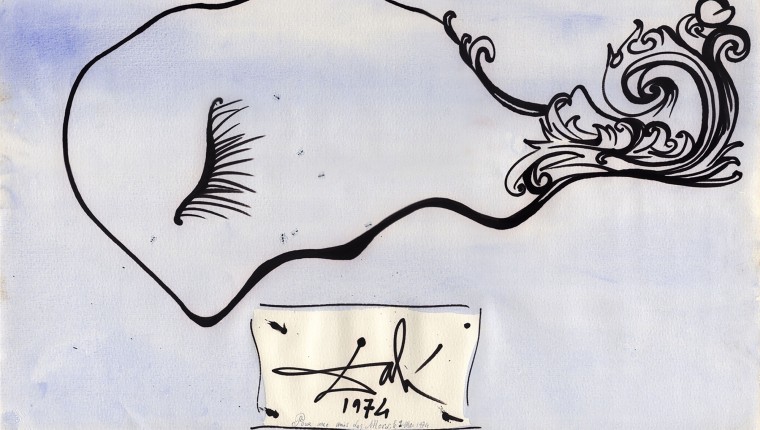

To make art

Not all the works on paper were done just for the artist’s own edification or amusement. A number of the drawings are intended as finished art.

The Hysterical Arch, Combat, and Future Martyr of Supersonic Waves are signed and dated, which indicates that Dalí regarded them as end results.

“There is no possibility of cheating. It is either good or bad,” he says.

The art set before us IS the statement – it is good.