January 13, 2020 | By Eric Snider

Artist and Black activist John Sims premieres

two intense and timely installations at The Ringling

Beginning January 18

Online and at The Ringling Museum of Art

More here

. . .

Multimedia artist and provocateur John Sims can’t precisely explain how he came to embrace social activism at a young age. Black consciousness was apparently coded in his DNA — and, “I grew up in Detroit, one of the Blackest cities in America, in the ‘80s, with Public Enemy and Spike Lee,” he said in a phone interview. “It gave me a lot of confidence. I learned early on that I’m not afraid of white people.”

That confidence and fearlessness will be on vivid display at The Ringling in two related art installations: 2020: (Di)Visions of America and Afrodixia, which Sims premieres as the museum’s 2020-2021 Artist in Residence.

The shows represent Sims’ panoply of media – visual imagery, words, music, performance and even a simple (and fun) video game called KoronaKilla. “[The installations] really deal with three main things – the pandemic, American policing and a pushback on Confederate iconography,” he says.

The shows open on January 18, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Day. Find the details of Afrodixia here and 2020: (Di)Visions of America here.

It goes without saying, but I’ll say it anyway – Sims’ exhibits could not be more timely.

The installations’ central images are Confederate flags that have been recolored (i.e. red, black and green) and in doing so, heist, subvert and appropriate racist iconography.

(Di)Visions also includes Sims-penned op-eds that ran in the Tampa Bay Times. . . Dear Police, an open letter read by Sims like he’s talking through a police scanner; an evolving self-portrait; and KoronaKilla.

The artist also chose three Black women — Chandra Carty, Natasha Clemons and Lisa Merritt, MD — to read their own letters on the topics. “It’s call-and-response,” says Sims, referring to one of the central elements of African music and storytelling. “These women bring an authentic voice that is powerful and unique.”

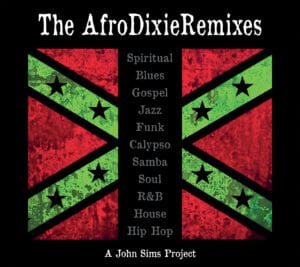

AfroDixia features what Sims calls the “world’s largest Afro-Confederate flag” along with the artist’s ambitious, 13-year music project, The AfroDixie Remixes, playing in a loop. The music deconstructs the song “Dixie” — the anthem of the Confederacy — into blues, gospel, jazz, reggae, hip-hop and more.

AfroDixia features what Sims calls the “world’s largest Afro-Confederate flag” along with the artist’s ambitious, 13-year music project, The AfroDixie Remixes, playing in a loop. The music deconstructs the song “Dixie” — the anthem of the Confederacy — into blues, gospel, jazz, reggae, hip-hop and more.

The 14 versions showcase an array of local and regional artists, including singers Twinkle, Ally Couch and Michael Mendez, the late jazz pianist Kenny Drew, Jr., and hip-hoppers Geno and Skunk Boogie.

“A lot of the musicians work on [Sarasota’s] Main Street,” Sims says. “I feel it’s important to elevate and celebrate the work done in the community.

“I had Ally [Couch] do three different versions – Etta James, Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald. I chose the Billie Holiday one. I directed her to give it a ‘Strange Fruit’ feel,” he adds, referencing a mordant dirge about lynching that Lady Day first recorded in 1939. The song played a pivotal role in the nascent Civil Rights Movement.

When talking about the Afrodixia venue — the museum’s august Historic Asolo Theater — Sims’ voice booms with exuberance. “Can you imagine a better cultural symbol of power and white supremacy than an opera house?”

• • •

Sims, 52, grew up in a single-parent home on a mixed-race block in Detroit’s working-class west side. It was not an activist family, but his mother “was religious, and going to church three times a week set me up for going to class, listening to lectures,” he says with a laugh.

At Renaissance High School, he took both conventional and vo-tech classes, and developed advanced skills in math and technology. At the same time, he gravitated to hard-left politics. “I was running with socialist folks and unionizers in the city,” he recalls. “I had my own Trotsky tutor. We met Wednesdays at McDonald’s.”

Sims attended ultra-liberal Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, where he developed concepts in the realm of “math art,” a discipline that’s still very much part of his work.

After graduating, he founded and organized The Cross Cultural Field Program, a slate of 26 events celebrating the African-American experience (including performances by R.L. Burnside and Henry Threadgill) as well as taking a diverse group of students on a journey to see Black culture up close in Charleston, The Sea Islands and rural Georgia.

“I learned how to organize other people,” Sims says of his time at Antioch. “Organizing becomes its own art form.”

His years at the college also instilled a propensity for collaboration, allowing him to consider “how we develop the social element, social art, so that we can respect each other and do things together.”

A Sarasota resident since the late ‘90s, Sims has shown his work and lectured in New York City, Detroit, Gettysburg, Paris, Israel, Argentina, Slovenia, at various colleges in Ohio and an array of venues in Florida. His art caused a stir in Tallahassee.

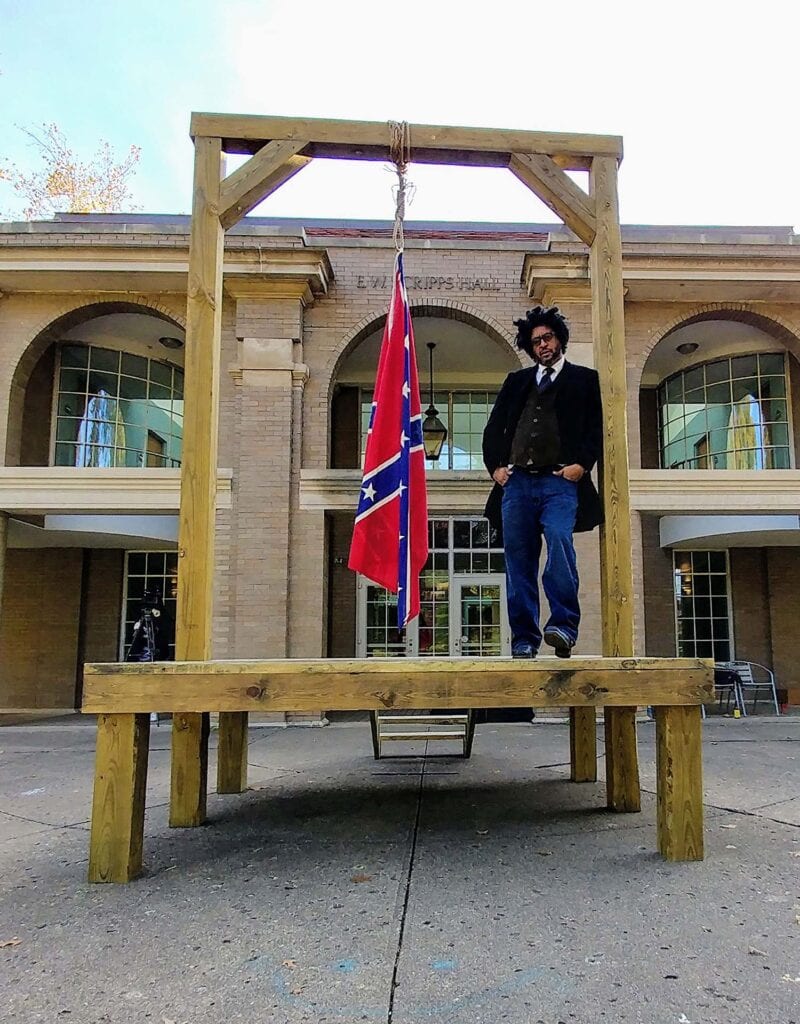

Arguably Sims’ most powerful piece, The Proper Way to Hang a Confederate Flag, features the “Stars and Bars” drooping from a noose in a 13-foot wooden gallows.

. . .

In 2007, he included it in a group exhibition at the now-defunct Brogan Museum in Florida’s capitol. The Sons of Confederate Veterans got their dander up and protested, citing a 1961 Florida statute that makes it unlawful to deface or defile the “flag or any emblem of the Confederate States.”

(The law is still on the books. Sims set up an online petition and has talked to state legislators about getting it repealed.)

When the The Sons of Confederate Veterans failed to get Sims’ piece pulled, they demanded to mount their own counter-show to celebrate the flag. “I told [the curators] if they allowed that to happen to pull my shit out,” Sims says, adding that in the end the Sons “whimpered away, but the threat did make me aware of the statute.”

From the late ‘90s to 2005, Sims worked as the coordinator of mathematics at Ringling College of Art and Design, where he crafted a visual mathematics curriculum for artists and visual thinkers. He also curated more than 15 math art exhibitions that showcased his work and that of other prominent artists.

Sims says he’s made a living as an independent artist for 15 years. It has required juggling an array of creative projects and activist endeavors, as well as marketing himself and his work. “I just keep my focus and drive steady,” he says. “I don’t have a family, so I can focus on the work, sell to who I want to sell to. I’ve built a foundation and now I’m building vertically. I’m in five museum shows this year.”

• • •

Sims and I conducted an hour-long phone interview two days after the infamous attack on the U.S. Capitol building. We were both still processing the event.

His take was measured, betraying no obvious anger. “I think this was the last stand for the kind of anxiety that white male Republicans and radicals feel about losing power,” he says. “They are really concerned about losing power because America is diversifying. Trump is a metaphor for the kicking and screaming over losing that power.”

About what at first appeared to be a feeble attempt by police to repel the rioters, Sims asserts, “Deep down a lot of them are Trumpers. They saw themselves in the crowd. The police also knew that if they started shooting, the crowd would start shooting back. The folks rioting were willing to die or go to jail. The powers that be didn’t want to have the military go in and have like 250 people killed, lying dead on the ground.”

Later in the conversation, Sims spoke about what he hopes for in the aftermath of the assault on the Capitol building. “It just advances the reckoning of white supremacy, and that includes white supremacy on the left.

“To really address white supremacy and privilege, there must be real sacrifices beyond conversation. There must be budgets, jobs, policy and cultural commitment that Black lives, art and stories matter.”

• • •

2020 (Di)Visions of America debuts online on January 18 at at 7:30 pm in a performance recorded at the Historic Asolo Theater. The program will be rebroadcast on January 23 and 30 at 7:30 pm, and February 1 at 6:30 p.m.. Tickets are available here.

Afrodixia can be experienced in person at the Historic Asolo Theater from January 18-25, during Ringling Museum hours. It’s free with museum admission.

The Ringling is also hosting several online talks on equity and inclusivity in the museum’s collection, and on artwork depicting conflict and trauma. Find the schedule at ringling.org/events/virtual-talks-lectures.