What does your art mean?

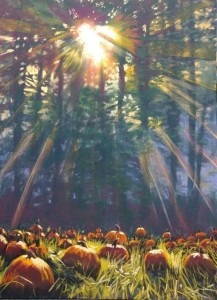

Ever see the light filtering through the trees and it leaves you gobsmacked-mouth agape in wonder, eyes wide with awe? Then you have experienced Transcendentalism. It’s a spiritual experience, the tree is more than just a tree, it is a spiritual being, illuminating your skin with shafts of warm sunlight, and filling your soul. The tree is the embodiment of “God” in this example.

The first time I experienced it, I stood in front of Frederic Church’s “Icebergs” painting at the Dallas Museum of Art, and my fate was set forever. I was barely tall enough to see the whole painting, and it took my breath away. The icebergs were crystalline blue, and green and towered massive in the scene. The only human trace or “hand of man” was a broken ship mast in the foreground. The painting told me that man was small and insignificant, and human impact would be temporary and fleeting. Nature was untouchable, something bigger and vaster than us, impenetrable.

I wanted that world. I wanted it to be true. I wanted to believe that people were inherently good, and given the chance, would change behavior to protect the environment. Truly we care about the coral reefs, don’t we?

Artists approach climate change the same way the public does; some make shocking art that confronts the issue head on, some allude to it and it informs their work like a color woven through the composition, and some seem to ignore it, never broaching the subject. Its important for me, as a Transcendentalist, to show the ultimate triumph of nature and the evolution of humanity above our selfish and self-centered relationship to nature.

For me the political is personal-the planet is feminine divine, the hand of man is the masculine divine, the yin and yang. Just as the hand of man can be shaped into a fist to cause harm, so it has the power to create solutions to the worst effects of sea level rise, species loss, and warming climate. The planet may seem inhospitable and unforgiving, yet also has the amazing power to heal and rebound. COVID gave us a glimpse. A few weeks without human activity and nature rebounded with a vengeance.

Transcendentalism is a word like “mysticism” or “romanticism” it holds little weight in our culture today. Transcendentalism is the philosophical movement from 1820’s touting the inherent goodness of people, self-reliance as the key, and putting immanence at the core of it all.

Transcendentalism defined the Hudson River School, and became famous through Emerson who wrote;

“In the woods, we return to reason and faith. There I feel that nothing can befall me in life, — no disgrace, no calamity, (leaving me my eyes,) which nature cannot repair. Standing on the bare ground, — my head bathed by the blithe air, and uplifted into infinite space, — all mean egotism vanishes.”

It is hard to imagine mean Egotism vanishing-that force that drives humans to conquer and name things after themselves, then wage wars to keep them, or acquire more, more, more!

Native peoples all over the world had the right reverence for the land-that people are of the land, belong to the land, not the other way around. How vastly different our country would be, and our world, if the West was not won, but the settlers learned to share equitably with the Natives who were already offering to do so.

I studied semiotics for a brief period in college with an artist named Vernon Fisher at University of North Texas. Semiotics is the study of language and combining disparate images to make a statement. Your mind does this involuntarily. You look at an apple and an empty pie plate and think “Mmm apple pie!”

I use semiotics in my work. Many artists do and it’s nothing new. Allegory was born with Greek mythos. Brides are symbols in our culture; hopeful princesses in white gowns filled with pure goodness, ripe fruit, completed by a man and ultimately children, a role to be fulfilled. What if she runs away? Turns her back on society and strikes out into the great unknown? What would our world look like without roles, expectations, oppression?

In “Over My Head” the bride is personalized, floating, presumably dead, in a sea filled with jellyfish-the only creature we don’t overfish, and the one most likely to survive in warming seas. What’s drowned is not the feminine divine, it’s the role of bride, the innocence, the white dress, the expectations. In Freudian dream interpretation the ocean is a symbol for deep emotion. The bride is “over her head” in love? Climate change? Both?

Over My Head, Shawn Dell Joyce

I am that bride. I hope all will identify at some level with me. These paintings are autobiographical in that they are embodiment of feminist emotion in a masculine society. Each runaway bride is letting go of a female stereotype, a societal norm, or sex role.

The runaway bride is potential left unfulfilled; the woman in her peak of ripeness would rather turn to the woods then fulfill her scripted sex role.

Some paintings are less clear in the semiotics yet carry a deeply Transcendental message. In “Wind Riders” the composition shows a crashed sailboat in the foreground with a storm moving over the Skyway Bridge in the background and an egret in flight between the two. The sailboat portends disaster, the bird is a witness unaffected by the storm. It speaks of the rise of the empire and eventual fall which was a recurring theme in Hudson River School paintings, especially by Thomas Cole.

“Wind Riders” Shawn Dell Joyce

A number of women were associated with the Hudson River School. Susie M. Barstow was an avid mountain climber who painted the mountain scenery of the Catskills and the White Mountains. Eliza Pratt Greatorex was an Irish-born painter who was the second woman elected to the National Academy of Design. Julie Hart Beers led sketching expeditions in the Hudson Valley region before moving to a New York City art studio with her daughters. Harriet Cany Peale studied with Rembrandt Peale and Mary Blood Mellen was a student and collaborator with Fitz Henry Lane.

In their paintings, as in mine, Nature is witness to man’s folly. There is always some “hand of man” symbol; cut down trees, steam engine, or in my case, skyscrapers on the horizon, telephone wires, cars. But nature is the main focus and larger story. The women of the Hudson River School believed in plein air, and were bold enough to buck fashion and paint alongside their male counterparts.

Imagine how difficult it must have been in the 1850’s to hike wearing heels, stockings, corset, petticoats, long dresses, pillbox hats, AND carrying your easels and paints. Yet, many did. Some of these women were single moms, who had to wrangle child care in order to paint. Today, its considerably easier, and more comfortable to paint outdoors and more socially acceptable as well.

Women of the Hudson River School depicted unspoiled landscapes, mountain cloves and streams that are now developed into neighborhoods and towns. Today, its near impossible to find an unspoiled landscape. One where you can look in all directions and not see (or hear) the hand of man. In Florida, we are running short on wild spaces. Most of the places I paint are preserves, places already set aside as wildlife habitat, or kept safe from development for now.

I’d like to think that we plein air painters are also chroniclers of this time and place. We paint this place at this moment in time. It won’t look the same in five years, much less twenty. The Seminoles who inhabited this area would not recognize it today, just as the Timucua, Calusa and Apalachee would not recognize it.

Maybe we are making some historic record of our time in this place, documenting the beaches, open space, architecture, small businesses. Only future art historians will know for sure.