April 28, 2021 | Curated by Gloria Muñoz

. . .

Hello Rookery Community,

We’re happy to share the second issue of our quarterly creative writing feature, The Rookery. This issue features a short story by Tenea D. Johnson from her recently published Broken Fevers, a poem by Anda Peterson, a

short story by Chelsea Catherine, and a poem by Linda Lucas.

This month has been a whirlwind as my poetry book Danzirly was published! Besides the book launch, it’s been a month of reflection. We’re past the one year mark of the pandemic and friends and family are slowly rebuilding, changing and rethinking their priorities.

The non-stop racial violence against Asian, Black and Brown people has stopped me in my tracks and made me consider what my role is in my community. I’m thinking about what it means to be a bystander, what it means to Say vs. Do, and what I can do to help.

How can we each listen and support each other a little more? What is the role of writing in all of this? Well, reader, this is something for each of us to consider as we evaluate our own habits and biases. For now, I hope you find respite in the worlds and words built by this issue’s writers.

Gloria Muñoz

The Rookery Editor & Curator

Upcoming poetry reading at Tombolo Books on Thursday, 4.29 at 7 p.m.

@bygloriamunoz

. . .

The Rookery accepts poetry, flash fiction, fiction, creative nonfiction, comics, visual and hybrid work.

We welcome writers to submit work for consideration via our submission form here.

We are an inclusive creative writing series that is dedicated to holding space on the page for voices

that are often marginalized in publishing including people of color (BIPOC), trans, queer,

non-binary, LGBTQ+ people, people with disabilities and people of all ages.

How the Carters Got Their Name

By Tenea D. Johnson

. . .

A lot of Black folks are walking around with their owner’s last name. Or rather their ancestor’s owner. Others are a little luckier. They’re Johnson from Son of John. Baker ’cause that’s what they did. Cobbler from the skill it took to earn that name. Ezekiel was one of these last. Sometimes he wished he were a son of John, though — ‘cause the Carters had earned their name in death and revolution.

His grandmother only told Ezekiel the story once. He had just finished weeding their garden and stood in the kitchen, gulping down sweet iced tea. Outside, it had been hot like it only got in the moist river valley of Kentucky: hot enough to take notice, but not to impose too much on the beautiful day. Grandma Maddie called him into the living room. She sat in her overstuffed armchair, watching one of the reparations protests with the sound turned off. A throng of brown faces filled the small screen, mouthing the same words. Their expressions said more than the placards they held, articulated their position better than a thousand raised fists. Grandma Maddie looked up from the scene and told Ezekiel to sit so she could tend to the rose bush scratches riddled down his arms. He settled at the foot of her chair, his shoulder resting against her knee. With both of Ezekiel’s parents long ago passed away — his mother, into the grave, and his father, into the night — Ezekiel and Grandma Maddie shared the small confines of their country home with an uncommon grace.

Grandma Maddie plucked a fat leaf from the plant that stood on the chest near her chair. Above it, a blurry black and white daguerreotype of her great-grandmother hung. Only their expressions differed. Ezekiel’s grandmother had deep laugh lines and a ready smile. The woman above looked as if someone had carved worry and hard work into her brow with a sharp stick.

Grandma Maddie broke open the aloe leaf. As she slid her finger through its milk, Ezekiel laid his arm across her lap and began to relax into the folds of her skirt.

“You did some good work out there today, Zeke,” she said. “Should be able to get those cabbages into the space you cleared. Maybe some squash and more room for some yellow tomatoes.”

She said this to watch Ezekiel’s face screw up in disgust, knowing how much he hated tomatoes, yellow or otherwise. Even in these food-lean times, when gardens were a necessity and livestock a luxury, he would rather go quietly hungry than eat them. She never tired of the joke, and unlike most twelve-year-old boys, neither did he.

Ezekiel had never been like his peers. His genius made him different. Though applying to biology programs left little time to spend with other kids, he doubted they would want to be with him anyway; his daddy didn’t. Even with his stratospheric IQ, Ezekiel didn’t believe that women or prison or selfishness had kept his father from him — though his Grandma Maddie, the man’s own mama, had told him as much.

Because of his father’s absence, or perhaps in spite of it, Ezekiel made it his business to know everything there was to know about being a Carter. He had almost exhausted what Grandma Maddie thought it proper to tell him. The Carters, it seemed, had been a raucous bunch right up to his grandmother — though really, it had been her “dealings with women” that earned her the title. She loved to put it that way, heavy on the sarcasm. The Carters, she said, lived loud because they knew that they would die young.

They didn’t die from bullets or barroom brawls or overdoses either. Their bodies just turned on ’em one day, made them suffer like hell for a spell, and then gave up with the soul inside screaming. That’s the way Grandma Maddie always put it. She had a way of putting things.

On this particular day his grandmother decided to acknowledge his burgeoning manhood by way of telling Ezekiel how the Carters got their name.

“Zeke, today I’m gonna tell you something special.” She dabbed the aloe under his eye where a deep groove of blood had sprouted. “Boy, how’d you do that? Looks like it hurts like bajeezus.” Looking into his eyes, she said, “You gotta be more careful with yourself.” She stroked the soft dense hair on his head. Ezekiel moved closer, breathed deeper.

“It ain’t a pretty story, but it’s the truth.” She paused, collecting another swipe of aloe from the reserve on the back of her hand.

“A lot of Black folks are walking ’round with their owner’s last name. Or rather their ancestor’s owner. Others are a little luckier. They’re ‘Johnson’ from ‘Son of John’. ‘Baker’ ’cause that’s what they did. ‘Cobbler’ from the skill it took to earn that name. The Carters are like that.

Way back before you or even I can remember, we was slaves. Not like the processing pools in Brandermill or even the way them reparations people talk about it, but real slaves. Hanging tobacco, sweating in the fields, hearts long broke. There are stories for every one of them days, but this is about the day before the day we got our name.

The way it was told to me, a young girl had been taken in the night by the overseers. In front of her mama. Which, unfortunately, was nothing new. But on that day something in the mama snapped — like a stepped-on stick that whips up at the one who broke it.

She started screaming and jumped on them overseers. Went straight for the eyes, as it was told to me. She broke noses when they tried to restrain her, shattered teeth, closed windpipes with her bare feet, kicking out against all those restraining arms and hands.

Four men couldn’t stop her fury, the protecting of her child. Outside the cabin the people had started to gather. As it was told to me, their eyes filled the small window and doorway of the cabin. They watched as the mama blinded two of the men, and was working on a third when the head man, himself, came barreling through the doorway and shot her right there — back of the head, like a coward would. Blasted her all over the cabin and the screaming child. By the time the echo cleared, all hell had broken loose.

The people had caught a fury. Any other day, they might have dragged themselves away. In the morning they would have cried for the woman slung up on a tree, split from hind to head. But not on that day. There was no reason other than their lives.”

Ezekiel’s eyes nearly vibrated in their fullness. He didn’t realize that he gripped his Grandma Maddie’s thigh like the last solid thing on an endless sea.

“They ran, not to the paths that led through the woods, but straight toward the bright house on the hill. Some were shot down before they’d even gone a few steps, picked off by the head man. Their arms reached out even in death, trying to grab some of the vengeance surging toward that house. They lit fires in the field as they went, moving as one. The people had no plan, no weapons. They carried only the weight of their years.

And with that, they tore the place apart.”

In his mind’s eye Ezekiel could see the people moving — splintering wood and tearing down doors. His gaze drifted to the television set, settled on the tumult that filled the screen. The two images merged — all these people fighting for something when there was so little left. The force of their union pulled him away from his grandmother and further into the world. He sat next to her, his back now so rigid and straight it seemed as if his shoulders were pulled from above.

“Soon enough, the head man found more men and more guns. When the shooting and screaming were done, and the birds came back to the trees to soothe the earth that had witnessed it, there were more bodies than people. The folks who had survived were beaten, strung up. Our ancestor, Brother, was one of the first to be put back to work, hefting and carrying the bodies of man, woman, and child. He placed them softly as he could into a waiting wagon. He was so good at the task, so swift and so strong, that they made it his job.” Grandma Maddie shifted in her chair and tilted her head with a sad smile.

“Brother worked the death cart until he was the one laid.”

Tiny scratches forgotten, Ezekiel wrapped his arms around his knees, head cradled between them. He gazed into a distance that he now knew he would someday meet. Grandma Maddie placed her hand on his shoulder.

“… And that, Ezekiel, is how the Carters got their name.”

. . .

After time well spent in alphabet cities — NYC, ATL and DC — Tenea lives near the Gulf of Mexico where she writes speculative fiction, makes music and builds an arts & empowerment enterprise. Her latest book is Broken Fevers, which earned a starred review in Publisher’s Weekly – next out is the fiction album, Frequencies. Her debut novel Smoketown won the Parallax Award for excellence in a speculative fiction work by a person of color. R/evolution, the first book in the Revolution series, received an honorable mention that year as well. She’s pleased to be a 2021 Creative Pinellas Professional Artist grantee. @teneajohnson

Hollow Through the Valley

By Chelsea Catherine

. . .

The dog is sitting on my porch again, huffing with his tongue out even though it’s close to forty degrees. He’s a short hair. His snout is long, like a Labrador, but there’s this round shape to his head that reminds me of the pit bulls my cousin used to train for fights.

“Why don’t you come inside?”

His tail thumps against the floor. I’ve been trying to get him to come into the house for a week now, but he won’t budge. He sits under that old porch swing and thumps his tail like an idiot. I’m not sure where he came from.

“Fine. Be cold.”

I exit the house, shutting the front door behind me. The air is cool this morning, strange considering the last few days have been brutal. I can barely see my breath as I exhale, taking the stairs until my boots come to rest against the frozen earth. Beyond the front porch, rows of red-violet grapes extend, bursting against thin netting. The ground is covered in a slim layer of snow.

When I first moved to Montana, I thought ice-wine was going to make me rich. While it has paid the bills, the picking has taken a toll on my hands and fingers and back. I pick and plant and prune. Stay busy. The cold air chaps my cheeks. The other day, I looked in the mirror and thought I looked sixty, even though I’m not yet forty.

This morning, the sun shines, the sky free of clouds. I take a bucket and begin picking the grapes. They are cold and hard, slick as I roll them between my fingers. I pick them and drop them in the bucket. Plink, plink.

I continue this for several hours, until the sun shifts and hits me in the eye. My back aches. I sit for a moment, looking up at the sky. There are almost no sounds anywhere. No birds today, no movement at all.

I take a peanut butter protein bar out of my pocket and start to chew on it when a huffing sound comes from next to me. It’s the dog. He’s followed me out here and now sits a few feet away in the snow and dirt, wagging his tail. “Nobody here is going to feed you,” I say.

He gives a small huff. I end up breaking off the end of the bar and handing it to him.

+++

Later that day, I bring the dog to the shelter downtown. It’s the responsible thing to do. He sits next to me in the passenger’s seat of the truck, wagging his dumb tail like he is going on an adventure. He licks the air once, then taps me with his paw. “We’re going to find you a real home,” I tell him.

I bring him in on a rope from the farm. The shelter is relatively empty – no painful shrieks – which makes me feel better about what I’m doing. It smells of lemon, a fresh clean, and the floors are free of dog hair and piss. Still, the dog sits with his tail tucked under his butt, forlorn and abandoned.

“How old is he?” the shelter assistant asks.

“He’s not mine.”

“I thought you were surrendering him.”

“He’s been sitting on my porch for a week, but he was never my dog.”

The girl is young, maybe just out of high school, and she looks at me the way I would expect someone that young to look at me. She is the age of the children my high school classmates have. Sometimes I see their pictures on social media and wonder what it might’ve been like had Edie and I chosen to adopt. But now, I’m thankful we chose against it. I could not be a mom without her.

“Does he have behavioral problems?”

I stare at the girl. “How should I know?”

She pauses, then reaches for the leash. “Sure.”

My skin prickles. I hesitate for a moment, my hand clenched around the frayed end of the rope. Then I’m giving it over to those nail bitten fingers. The dog looks up at me. He has a small eye booger on his left eye. I reach out and wipe it away with one finger. “He’ll be safe here?”

“We’re not a kill shelter,” the girl says, pulling the dog closer.

I clutch my chest, where a small pain has sprouted. “Fine,” I tell her. “Good.”

+++

The next morning, I wake up wondering what the dog is doing. Are they feeding him now? Does he get dry and wet food or just crappy kibbles? Maybe he is still sleeping. I imagine he has a mat in the shelter, and it is temperature controlled so at least he’s not cold anymore.

I get out of bed. Wash my face. Throw on some work overalls. My body moves slowly, aching from picking the grapes. My throat is tight, but I don’t know why. Sometimes I just cry for no discernible reason. The grief therapist said it is to be expected. There is no reason to rush my healing, he said, but I still feel this pressure. After Edie died, I moved here, started over. I stopped drinking and started working the land. I read all the self-help books. But still sometimes I wake up in the mornings and the world feels so empty, it’s hard to get out of bed.

The downstairs is cold this morning, and the tiles burn the bottom of my bare feet as I walk. I make coffee and sit next to one of the kitchen windows. The Kaniksu National Forest rises, a curved, baldheaded peak, pale in its rock shale and scattered with pines. The sky stretches everywhere. It is so blue and pale and never ending here, one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever seen.

My phone rings. “Your dog has escaped,” a woman states.

“He’s not my dog.” I pause. “How’d he get out?”

“We’re not sure.”

“But weren’t you watching him?”

She says they lock them up at night, but this dog is smart and found a way out. She asks me if he knows the way home and I tell her my house is not his home. “He might know how to get there, though,” she says.

I grow frustrated and hang up. The dog would not want to come here. Why would he? The farm is functional. It’s a place to live, not a home. He won’t come here. He probably doesn’t even know how to leave the downtown.

Still, I put on a winter hat and head outdoors. The air is tight and biting. It’s like ice against my skin. I check under the porch, but he’s not there. He’s not in the barn either, or in the fields. I call for him for five minutes, but he doesn’t come running from the rows of grapes, his one ear flopping against his head.

+++

Ossler is a town where people come to die. Most of the local commerce is based around the assisted suicide clinic. I pass it as I drive downtown that afternoon, looking for the dog. The snow is packed tightly here, thin and solid on the sidewalks. All the plants are dead, and everything is covered by dirty snow. A soft sheen of salt rests on the grey concrete. Beyond the edges of the buildings, a mist creeps in, blocking out the snow-covered mountains in the background. Fresh powder is on the way. Maybe a big storm. I can tell by the way the air smells. The dog will not survive it.

For ten years, I had a Jack Russell who followed me around everywhere. But then when a coyote got to him in the back yard, I decided I would have no more dogs here until I can figure out how to keep them safe. Here, we have storms and wolves and droughts. There are miles and miles of nothing in either direction outside the town. The dog would find his way out of the house and wander. I just can’t take that risk anymore.

I round the police department as the first snowflakes start to fall. They are small and sparse at first, but by the time I make it to the high school, they are thick and fat and frequent, clouding the windshield. Storms out here make a low howling sound. It’s like a soft moan, a hum that comes from wind barreling through the valley. It’s said to drive some people mad, but I have lived here for three years now and I’ve never seen anybody here that’s gone mad. People here arrive mad. They either die working the land, or they work at the clinic and a piece of them dies that way.

After making one last loop around town, I head home. In the rearview, I watch the storm clouds descend in front of the mountains, a mass of swirling grey headed straight towards me.

+++

Storms have to be strong enough to get over the mountains, which they aren’t very often. When they do, they come barreling through the valley, lashing against the sides of the mountain and turning everything into ice. When I first moved here, the storms scared me, but now I think they’re kind of an adventure.

I park in the barn and make sure the chickens are all taken care of and the barn is secure before walking over to the house. The wind has picked up and it springs tears to my eyes, dry and bitter like small particles of ice. The oak trees have bent against the wind, cowering over the house.

Even though it’s freezing, I force myself outside to pluck some of the remaining grapes from their branches, my fingers cold and slick with moisture. I’m halfway through a bucket when a soft whining sound comes from beside me. I look up. The dog sits to my left, huffing. A wave of relief washes over me.

“You escaped,” I tell him.

He wags his tail.

“I thought you didn’t like it here.”

He smiles, sticking his tongue out.

+++

The Jack Russell belonged to Edie. She got him when he was a puppy and named him Fred. We met not long later.

“Fred is such a human name,” I told her on our fourth date, after meeting the dog for the first time.

“And?”

“It’s interesting, is all.”

Edie smirked at me from across her dinner table. Her skin was still shining then, a lush brown that stood stark against her many bracelets. She humanized everything. The plants had human names, so did the pieces of her furniture. When we walked downtown, she would point out the historic buildings and tell me how long they’d been there, what their stories were. Everything was special to Edie. “Have you ever had one?” she asked.

“I grew up on a farm. They were all working dogs.”

Fred jumped up into her lap, nuzzling her neck. He had a pattern of spots on his back, like randomly dispersed droplets of water. Years later, after the cancer spread, the same pattern of spots popped up on Edie’s hand. I would look down and touch them, smoothing my thumb back and forth like it would help. “They don’t hurt,” she would tell me.

But each time I looked at them, I felt this pain in my chest, this overwhelming sense of doom and helplessness. One day, she was my Edie, and the next, she could barely remember how we met. I kept touching her hands, her eyes. “We’ve been in love since before we met,” I told her.

She didn’t remember.

+++

The storm rages for hours. The dog sits in front of the fireplace, chewing on a deboned chicken breast. He keeps looking at me and smiling, almost squinting his eyes, like he’s the happiest dog on the planet. I’m happy, too. I sit watching him and sipping a mug of lavender tea with honey and milk.

Snow rises outside the window. At first, the snow layer is barely off the ground, but as more powder falls, it inches its way up to the sill. By the time night falls, the wind is howling. It barrels through the slim valley, creating an intense droning sound. I turn on a WNBA game to block it out and end up falling asleep in the living room recliner.

When I awaken, the dog is sitting at my feet, wagging his tail. It’s cold in the room – the fire has gone out. The howling sound is gone and now everything is quiet. This kind of silence does not exist outside of Montana. Back home in the city, there are always cars honking, and music playing, and people walking outside. Here, there is nothing but the grape vines and the snow.

The dog places his paw on my knee.

“You’re still hungry?”

He has more chicken for breakfast and I eat oatmeal with brown sugar. We sit at the kitchen table looking out the window where the world is blindingly white. Later today, I’ll drive into town and get him some dog food and a proper leash. For now, I pour him some water in a bowl and watch as he laps it up, smiling at me again.

I have never seen a dog who smiles like this. It’s like Edie was – she smiled all the time, at every damn thing. She could not be discouraged from the world. Even when she was dying, she was so happy just to have been alive, and then there was me, so angry this was happening, so furious that I’d finally found my person just to lose her.

Now that the storm has passed, I suit up and head outside. The dog follows. Once in the yard, he gallops through the fresh powder, sticking his nose in it like it’s the greatest thing on the Earth. Watching him reminds me of how beautiful the landscape is just after a storm.

“Do you want to stay here with me?” I ask him.

He wags his tail, so happy and stupid. I’ve always been so jealous of dogs. They forget their hurts quickly. They find someone they love and hold on to them like there is no risk in the world. I want so badly to get back to that. Some days it feels close but not quite there. Baby steps, the therapist tells me.

“I’ll take that as a yes,” I say. My chest tightens a little, but I push it away. “Can I call you Smiley?”

His ears perk.

I finish shoveling the porch and then sit on the steps, tossing snowballs his way, watching him leap into the air, the sun shining off the moisture on his coat as he bites at them.

. . .

Chelsea Catherine is a native Vermonter living in St. Petersburg. In 2018, she won the Mary C Mohr nonfiction award through the Southern Indiana Review and her book Summer of the Cicadas was published in August of 2020 and won the Quill Prose Award through Red Hen Press. Most recently, she won an Emerging Artist grant from Creative Pinellas to work on her novel The Harvest. You can find her at chelseacatherinewriter.com.

A Father’s Lesson

By Linda E. Lucas

. . .

Loving the person

who does not love

back

enough

unconditionally.

Seeking the love

that is safe

gentle

fierce.

Finding the love from

mother

lover

sister

son.

Mother’s Day

one text, one call – a simple measure, an obligation,

a duty learned

to have a mother or mother’s day or lily gift wrapped.

Waiting for the flowers

or gift or love coming back, filling the vacuum, that vast field of lilies never

received or given

or taught.

. . .

Linda Lucas has taught economics and women’s studies in large and small, private and public universities and consulted with US, Canadian, Ugandan, Mexican and Thai government agencies. She is also a longtime political activist serving the Democratic party in elected as well as volunteer capacities engaged on campaigns, party building, voter protection and door to door voter recruitment. This is the first poem she has written in a long time.

Long Gone Chicago

By Anda Peterson

for my Childhood Schoolmate Fred Hampton

. . .

Hometown music

sets the groove

the sway

joy drum

saxophone shout

in this Florida coffee shop

where I sit writing.

Seventies Chicago rhythm and blues play today

as long ago

I took the elevated train past projects in a gray line

mountainous

over the expressway

the “El” clatters,

shakes the tenement windows,

screeches to a stop.

From the eleventh floor, a five-year-old watches,

this rushing world,

wonder-eyed, wish-filled

as the refrain

“Stand by me…”

floats out from his window

this summer day

of Chicago-heat-cemented

hot air blown about by a single fan,

“Darling, darling, stand

stand by me…”

the roar of the train deafens

deafens love songs.

I feel

faith in his heart,

not mine, but

unshakeable.

He watches

his brother waiting

sitting on the stoop

at noon

job denied

one more time.

On a Monday in my car, Marvin Gaye sings

“Makes me wanna holler,

throw up both my hands…”

the news interrupts

Fred

age 21

shot

dead

shot dead

while sound asleep.

I feel faith between the notes,

not mine, but

from a distance,

as I drive

to the South Side weeping

for my job at the welfare,

warfare office.

. . .

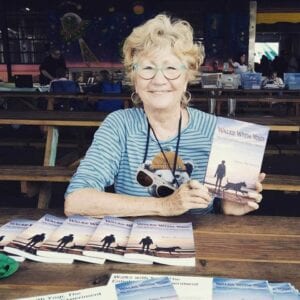

Anda Peterson worked as a teacher and counselor with low-income, at-risk youth in the Boston area for two decades. She earned her MFA in Creative writing from Emerson College in Boston and is an adjunct instructor of writing at the University of South Florida St. Petersburg. Her poetry has appeared in literary magazines like The Human Rights Festival of Art (NYC), Odet Literary Magazine and many more. Her feature stories appeared in The Boston Tab and Cape Cod Travel Guide. Her spiritual memoir, Walks with Yogi: the Enlightenment Experiment was published by Shanti Arts Publications, 2016 and is available on Amazon. walkswithyogi.com