September 12, 2019 | By Kurt Loft

A new exhibition at the Florida Holocaust Museum documents Tampa Bay’s own Civil Rights Movement through those who helped change their communities

On display through March 1, 2020

The Florida Holocaust Museum

More here

A young person growing up in the Tampa Bay area today would be hard pressed to imagine the degree of racism that divided us a half century ago. Yes, much of it lingers, here and in most towns and cities across the country, but not as the cultural and political dagger that once drew so much blood and hardship for African Americans.

Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana and other states in the Deep South served as the battle ground for the Civil Rights Movement in the 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s, while Florida’s role is often overlooked. But racism was no less extreme in Tampa, St. Petersburg and Sarasota, and the struggle for equality is woven into our local history.

This story unfolds in Beaches, Benches and Boycotts: The Civil Rights Movement in Tampa Bay, an exhibition running through March 1 at the Florida Holocaust Museum in downtown St. Petersburg.

“This is nothing new for our museum because we’ve had exhibitions and lectures that focus on civil rights for years,’’ says Erin Blankenship, the Museum’s Curator of Exhibitions and Collections. “We’re dedicated to bringing these stories to life because it goes to the heart of who we are, of fighting racism and inequality and hatred at all levels.’’

Told through dioramas, photographs, timelines and physical relics, the exhibition describes the hardships of people who lived here under oppressive Jim Crow laws. It documents how restricted covenants enforced segregation, both overtly and in less obvious ways. It depicts how black children attended underfunded segregated schools while white children benefited from more prosperous school districts. “Black only” hospitals, clinics, restaurants and beaches drew racial lines, as did the “white only’’ green benches around St. Petersburg parks and sidewalks.

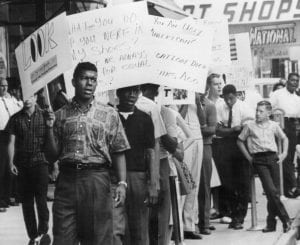

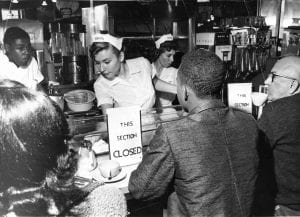

Photographs from the 1960s show sanitation workers picketing for equal pay with whites, who made an average of 75 cents an hour more than blacks in the same job. . . a St. Petersburg beach partitioned for blacks only. . . young protesters wearing white helmets as they marched down Central Avenue in Tampa. . . picketers outside a movie theater. . . and a sit-in at the Kress lunch counter in St. Petersburg.

The exhibition highlights the courage and vision of people who fought back and how their efforts galvanized entire neighborhoods. For her research, Blankenship relied on more than documents – she met with the people who lived through the era.

“We interviewed members of the communities in Tampa, St. Petersburg and Sarasota, so my source material came directly from them,’’ she explains. “It was really important to highlight these voices.’’

Walter Gilbert, 68, lived in Sarasota’s New Town in the 1960s and shared his experiences with the Museum.

“We knew, even at that early age, that we were living in a segregated system and it wasn’t made for me to advance too much further than they would allow,’’ he says. “My mother and father did what they could to protect me from the harshness of it all, but they also equipped me with the right tools.’’

For Gilbert, tensions were felt as soon as he ventured outside the safety of his neighborhood: “The community was self-contained. We were fine inside our community, but we couldn’t go downtown and go to certain shops and restaurants’’ without being separated.

The exhibition captures a pivotal moment in the area’s history. On February 29, 1960, a 21-year-old barber named Clarence Fort led the NAACP Youth Council in a protest at the whites-only lunch counter at the Woolworth’s department store in downtown Tampa. Unlike other civil rights protests around the country, this one was peaceful, even though Woolworth employees and customers were shocked by the demonstration, according to The Tampa Tribune: A Century of Florida Journalism, published by the University of Tampa Press in 1998.

“Diners at the lunch counter and store managers were absolutely flabbergasted when the group quietly sat down at the stools and booths and asked to be served,’’ the book notes. While Fort read from his Bible, police were called in and the Tampa Tribune and St. Petersburg Times rushed reporters to the scene. The meticulously planned sit-in made front page headlines in both papers.

The next day, black activists held nearly a dozen sit-ins at restaurants around the Tampa Bay area, and more and more merchants began to honor their requests to be served alongside whites. A door had been opened.

“I think this exhibition tells the story about the incredible bravery of these ordinary people who took steps to make changes for the rest of their community,’’ Blankenship says. “Everything in life for an African American was segregated back then. They could shop but couldn’t try on shoes or clothes. All of that changed because of the people who lived right here.’’

On display through March 1 at

The Florida Holocaust Museum

55 5th St. S., downtown St. Pete

Open 10 am to 4 pm seven days a week.

Call (727) 820-0100 or visit flholocaustmuseum.org