The Feminist Surrealist

Through January 7

Free

Dalí Museum

Details here

A new – and free – exhibit at the Dalí Museum is entitled Leonora Carrington: Writer, Painter, Visionary.

Note the label “Writer” comes before “Painter.”

That may seem odd to those who associate Carrington with visionary paintings, prints and sculptures — or with her early years living and painting with Max Ernst. Leonora Carrington, however, was not only a prolific visual artist, she also produced an impressive body of written works.

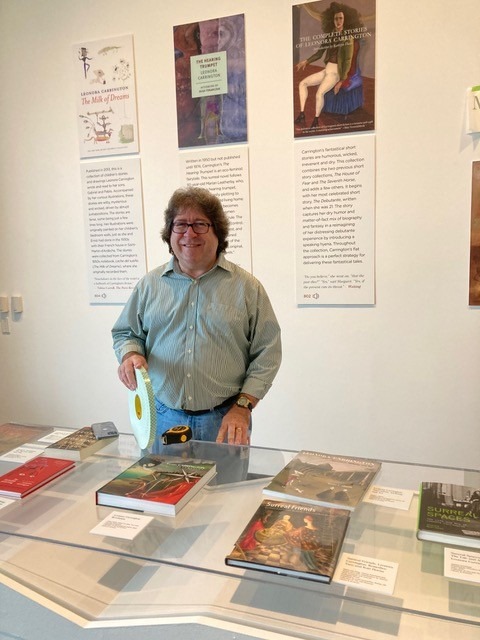

“People might know her as a painter, but they’re probably not as familiar with her as a writer,” says the Dalí’s Curator of Education Peter Tush who organized the show. This exhibit, he says, is an opportunity to show that lesser-known side of Carrington, using her books “as anchors” to tell her whole story.

And what a remarkable story it is. Born in England, Carrington burst on to the Paris art scene in the late 1930s with an enigmatic self-portrait (now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art) and an infamous liaison with Ernst, a leading figure of the Surrealist movement – all before the age of 21.

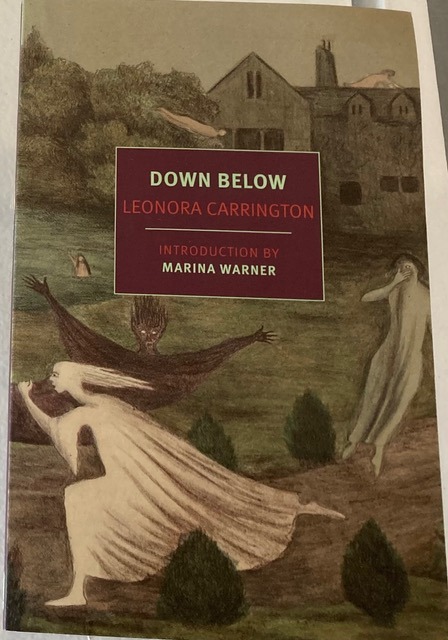

But her story didn’t end there. When Ernst was arrested by the Nazis, she fled France with friends for Spain, was confined in a Spanish asylum by her controlling father (where she had a nervous breakdown, chronicled in a haunting memoir called Down Below), escaped the mental institution thanks to a marriage of convenience and eventually ended up in Mexico City.

There she became a celebrated visual artist (producing over 2,000 pieces). And it was in Mexico where she produced the bulk of her literary output.

Despite this long and fruitful career, however, Carrington was late in getting the recognition she deserved outside her chosen homeland — as an artist and as a writer. Lumped in with the surrealists (a label she rejected), much to her annoyance she was constantly referred to as their muse.

“I didn’t have time to be anyone’s muse,” she famously said when people would bring up once again her link to Ernst decades after that affair was over. “I was too busy rebelling against my family and learning to be an artist.” (A quote, to my delight, that is included in this exhibit).

When she died in 2011, The Guardian ran this oddly dismissive headline: “Debutante turned surrealist Leonora Carrington dies at 94.”

Yes, she was technically a debutante, raised with her three brothers in a mansion with the pretentious name of Crookhey Hall, with its own croquet lawn and lake – but the British headline missed the essence of Carrington’s origins by a mile (or, as the Brits might say, by a kilometer).

Here, by contrast, is how the Dalí exhibit – in a text panel titled Youth – more accurately describes Carrington’s early years as a decidedly reluctant debutante and budding feminist.

“Born in 1917 in Lancashire, England, Leonora Carrington grew up in a strict aristocratic family. . . A rebellious child, she defied her privileged upbringing, leading to expulsions from two Catholic schools. . . In 1935, distressed by her father’s plan for her debutante presentation at Buckingham Palace, she vowed against such constraints. This inspired her iconic short story “The Debutante” (1937), a masterpiece of black humor.”

“The Debutante” tells the story of a young woman who frees a hyena from the London Zoo so the beast can take her place at her coming out ball – even agreeing to let the hyena kill and eat her maid, saving only her face, so the creature can hide at the ball behind a human mask.

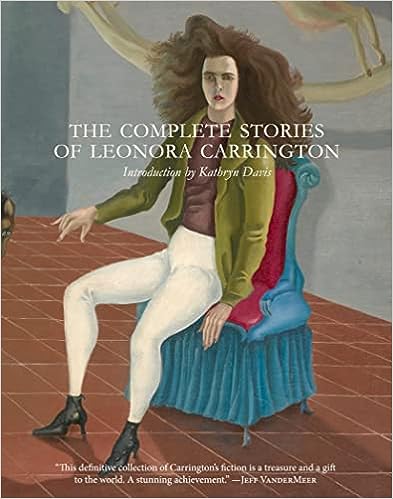

The gruesome story was one of many short stories featuring talking animals and fantastical themes — stories the show calls “humorous, wicked, irreverent and dry” — that Carrington would write throughout her long life.

The Dalí’s look at Carrington is the third in an annual series of fall exhibitions in the museum’s Raymond James Community Room dedicated to writers associated with Surrealism.

The first, launched three years ago by Dalí Museum director Hank Hine, was devoted to “Aimé Césaire: Poetry, Surrealism and Négritude,” the Martinique poet who was the father of the Négritude movement.

The second, in 2022, “Paul Éluard: Poetry, Politics, Love,” celebrated the poet who had been married to Salvador Dalí’s future wife, Gala.

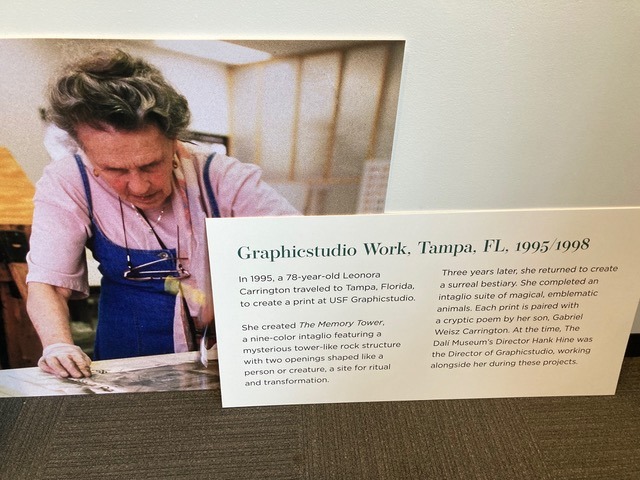

Hine has a personal connection to this year’s choice – he actually met and worked with Leonora Carrington in 1995 and again in 1998 when she came to USF’s Graphicstudio in Tampa when he was director there.

On her first visit to the studio, the 78-year-old Carrington printed a nine-color intaglio of a mysterious rocky tower with two openings shaped like a person and maybe a creature. She called the image The Memory Tower.

When she returned three years later she created a surreal bestiary, an intaglio suite of animals which she paired with poems by her son, Gabriel Weisz Carrington. In the section of this show highlighting Carrington’s time in Tampa, there is a photograph of Hine at her side in the studio and several of the prints she created there.

The prints are the only original artworks in the exhibit. Also displayed are two reproductions of Carrington paintings – that early self-portrait known as Inn of the Dawn Horse (it includes a hyena!) and a mystical painting of imaginary, ghostlike beasts that recently appeared in the Dalí’s Shape of Dreams exhibition.

But visual art is not the main attraction of this exhibit. The books are.

You can view dozens of them under glass in a long case set in front of the section devoted to Carrington’s time in Mexico. Among the copies of Carrington’s own literary works are two editions of the memoir Down Below.

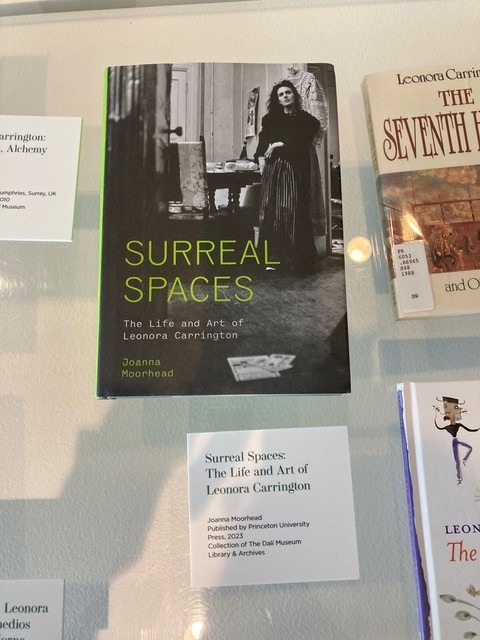

The nonfiction works in the case, such as Surreal Spaces: The Life and Art of Leonora Carrington, published this year by Princeton University Press, were used by Tush to research the exhibit’s written commentary.

On the walls of the exhibit are blow-ups of the covers of four major works by Carrington with a cellphone link that lets you listen to excerpts from each.

– Down Below, a memoir detailing her time in a Spanish asylum and her descent into madness, begun in 1940 when her partner Max Ernst was arrested and completed in the mental institution. Her loss of autonomy and her battles with escalating hallucinations are reflected in the memoir’s increasingly irrational narrative.

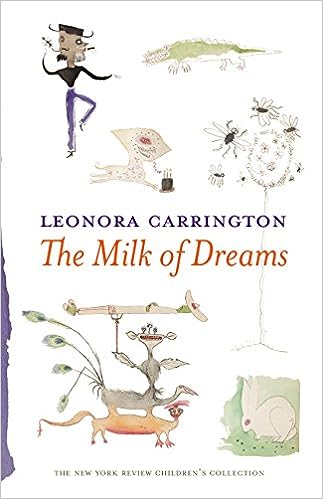

– The Milk of Dreams, a collection of “witty, mysterious and wicked” children’s stories that Carrington used to read to her two sons, Gabriel and Pablo, accompanied by the drawings that she drew on their bedroom wall. The stories, originally written down in a 1950 notebook as Leche del Sueño, were published posthumously by her son, the poet Gabriel, in 2013.

– The Hearing Trumpet, hailed by Scottish author Ali Smith as “one of the twentieth century’s most original, joyful and visionary novels.” It was written in 1950, but first published, in French, in 1974. Described as “an eco-feminist fairytale” and “tremendously weird,” the surreal novel tells the story of a 92-year-old Marian Leatherby who, using a hearing trumpet, overhears her family’s plot to place her in an old folk’s home where she goes and uncovers the world of the occult.

– The Complete Stories of Leonora Carrington, a collection of short stories that begins with “The Debutante.” This 1917 edition combines two previous Carrington collections, The House of Fear and The Seventh Horse, adding a few extra. Need a teaser? How about this quote from a story called “Waiting” – “Do you believe, she went on, that the past dies? Yes, said Margaret. Yes, if the present cuts its throat.”

Carrington is often referred to as the last of the first wave of Surrealists. I prefer to think of her as the first Feminist Surrealist.

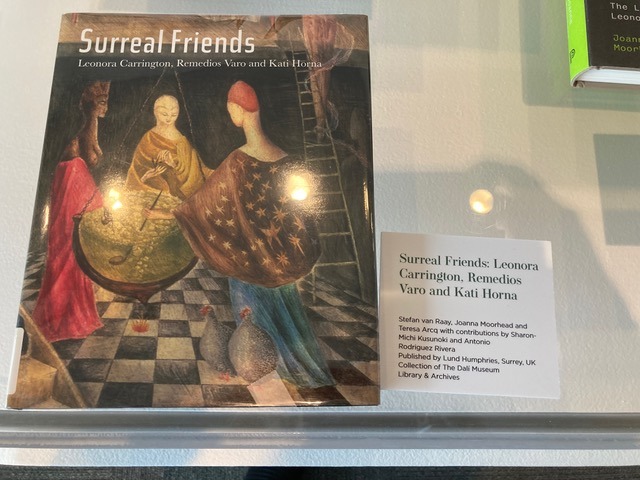

In Mexico Carrington married Hungarian photographer Emérico “Chiki” Weisz and gave birth to two sons, but she also formed deep bonds with two creative women who also were immigrants there – Spanish surrealist painter Remedios Varo and Hungarian photographer Kati Horna (who took the photo of her marriage to Chiki included in the exhibit).

All fervent advocates of women’s rights, the three women met regularly (“in the kitchen,” Peter Tush told me) to explore the subjects that interested them most – the occult, delving into magic, alchemy, tarot, kabbalah and religious rituals.

I like to think that these meetings were an extension of those conversations Carrington had with that female hyena at the London Zoo decades before. A meeting of kindred souls, advocates of women’s rights, who knew they would have to seek each other’s help and go to extraordinary means to have their voices heard in a world that was stacked against them. A community of like minds whose determination transcends time.

“Nonchalance in the face of weird is a hallmark of Carrington’s fiction,” Tobias Carroll wrote in 2013 in a Paris Review article championing her then primarily out-of-print work. Her literary output, he concluded 10 years ago, “deserve reconsideration; their vivid imagery, irreverence, and surreal transformations are as provocative as they were at the time of their writing.”

It’s taken a decade, but many of us are discovering just how relevant Carrington is in our own weird world of feminist backlash.

Go to Leonora Carrington: Writer, Painter, Visionary, which runs through January 7, 2024, and listen to her words.

Contemplate her whole story. It may just inspire you to action.

Coffee with a Curator

More on Leonora Carrington

October 4 from 10:30-11:30 am

in the Dalí’s Raymond James Room

and Online

Free

Peter Tush presents a talk on the life and work of Leonora Carrington, touching on the fantastic and occult within her writing, painting and life, exploring her strict upbringing, partnership with Max Ernst, association with the surrealists, incarceration in a Spanish asylum, and rise to become one of Mexico’s most important and beloved artists.

Find links to register for in-person seating

or to watch live via YouTube here.