Although it is 2022, rich memories still linger for the Black population who grew up in segregated south St. Petersburg. Today gentrification has removed or “silenced” much of the historic black neighborhood of 22nd St. South famously known as “the Deuces”. The new generation of young people know little about the area in which they have now captured for restaurants, bars and art galleries. When I moved to Florida in 1997 and lived in South St. Petersburg many acquaintances (in the art world) voiced their apprehensions about living “down there.” Misinformed and filled with old time fears most stayed away and never set foot “down there.”

Today new concerns have surfaced as discussions take place with the city about the development of Tropicana Field, which was once an African American community, dislocated many years ago to make room for the ballpark.

In October of 1997 I married Paul, an African American man who grew up in South St. Peterburg during segregation. He is the best storyteller, often telling me captivating and funny stories about his childhood days. I got an inside history of the makings of a strong thriving and successful African American community in the schools, businesses, churches, and families.

Did you know that in the 1930’s the Kul Klux Klan marched through his neighborhood declaring St. Petersburg a “white man’s city”? The community fought back and stood up to the injustices thrown at them. Although Paul was born in 1948, he says he only heard stories about the KKK from his peers but didn’t experience the lynching’s, terror and hatred perpetrated against the black neighborhood. What he did experience was the racial divide that confronted him every day even as a young child. Black people were not allowed to stay in Gulf Port after dark. A warning bell sounded when it was time for black hired hands to leave. They were also not allowed to be on Central Avenue much less sit on the now popular green benches! They were confined to a certain area which his friend, Jeffrey, would call “the colony”.

They were so separated from the rest of white St. Petersburg, Paul commented, that he didn’t have contact with any other people outside the black community. In spite of this, he has no regrets no hostilities, no anger from growing up in a hostile environment. At the time he didn’t care because he had fun growing up. With a tight community and strong family ties each person in South St. Pete looked out for the good of the other. Businesses thrived, supported by the community where they shopped, ate, and socialized. A true sense of dignity and belonging emerged from the close-nit community.

Paul recounts the time as a young boy living on 18th St., meeting some of the most famous black baseball players. Because the hotels and businesses in downtown St. Petersburg were for “whites only”, black ball players who came up for Spring training were not allowed to stay there. His mother Ethelyn, an English school teacher, opened up her home giving them food and a place to lay their heads while they were in training.

One time, Paul recalls, Frank Roberson ate every day at his grandmother’s table. Frank, who had won the most valuable player of the year, parked his prized white Cadillac Eldorado in their driveway! In the other driveway sat a corvette owned by Ellis Burton of the St. Lewis Cardinals. As a young impressionable 7th grader, Paul with the help of his friends were thrilled to help him wash their cars. They stood in awe of the successful African American ball players. But he says he often wondered why these ball players who were making so much money could not even sit in a restaurant in downtown St. Petersburg and have a meal.

Another memory of fun times growing up was when, after playing ball with his buddies, they would pick up old soda bottles and cash them in for two cents a bottle at Phillips Market on 16th Street. With the small change in their pockets, they walked to Web City and bought double ice cream cones. The highlight of their escapades was to stand in line at the “White Only” drinking fountains which infuriated the older white people. This intrusion caused great opposition from the white establishment, who angerly chased them away. You see, Paul explains, the water fountains for the white people had cold water while a few yards away the “Coloreds Only’ water bathroom sink spewed warm water from a hose protruding straight up in the air.

In 1966 the government integrated the schools and black children were bused out of the community to attend all white schools. Paul was bused from 18th St. South to 34th St. south to the only black high school in St. Petersburg. He says he had a good education while attending Gibbs High School. He recalls those days when having all black teachers were of great value to the youth growing up. They had a sense of pride and the teachers instilled strong values, good study skills and a high degree of learning.

Integration was only the beginning of the demise of the once great African American community. As people moved out of the neighborhood to shop elsewhere prosperous businesses lost their patrons and had to shut their doors. But, says Paul, the biggest disruption to the thriving black community was the building of the interstate which cut through the middle of the community and divided the neighborhood. When the state of Florida Department of Transportation decided they needed this land they didn’t care that it would destroy the Black community. They offered big money to relocate people to other parts of the city.

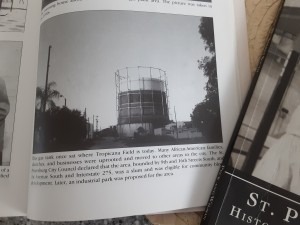

Adding to this demise, was the relocation of hundreds of black families living for years in the area known as the Gas Plant neighborhood, in order to make room for today’s Tropicana Field. Paul grew up in this neighborhood. In the 1980’s St. Petersburg City Counsel declared this to be a blighted area justifying their decision to use the land to build the ballpark. The parking lot for the games was once home to a large African American community. Back then they made promises for economic development and better housing facilities but never came though on their promises.

Today as the Tampa Bay Rays are not renewing their contract new discussions are taking place (of which Paul is a part of) and new development plans are on the table for Tropicana Field; plans for low-income housing and available loans for new business proposals. As new plans are being developed Paul is again wondering if the government will keep their promises. He interjects that years ago promises were made and not kept. He hopes it will be different this time and the city will honor the African American families that were uprooted many years ago.

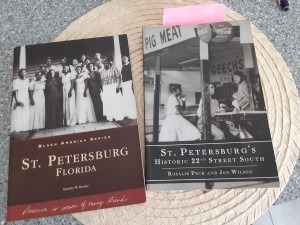

Image courtesy of Sandra W. Rooks book Black American Series St. Petersburg Florida

Image courtesy of Sandra W. Rooks book Black American Series St. Petersburg Florida

To find out more on this subject please view this link.

In the News – African American Heritage Association of St. Petersburg, FL, Inc. (afamheritagestpete.org)

https://afamheritagestpete.org

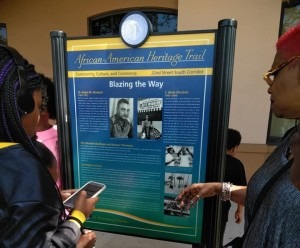

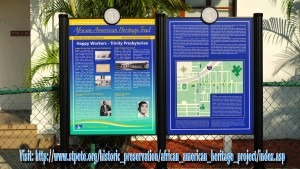

Fortunately, the history of St. Petersburg’s African American community has been kept alive by many prominent people who lived and grew up in the area. Using pictures, oral stories, and books, the history has been written and documented. Recent signage placed in strategic places along the African American Heritage Trail tells the story. Gwendolyn Reese, a classmate of Paul’s, and President of the African American Heritage Association, works diligently to keep the city of St. Petersburg and the public in general aware of the importance of knowing this important history. In 2006 Jon Wilson and Rosalie Peck published the book titled, St. Petersburg’s Historic 22nd Street South. A comprehensive account of the joys and sorrows of growing up in segregated South St. Pete. In 2003, author Sandra W. Rooks published her book, Black American Series, St. Petersburg Florida with pictures and the history of prominent residents, businesses, families and churches from the early days till now.

Visit the African American Heritage Trail and gain better incite to the area they called “The Deuces”.

https://www.visitstpeteclearwater.com/things-to-do/…