January 21, 2019 | By Eva Avenue

Through March 1

The James Museum

Details here

Picture it: New Mexico, 1943 — a little girl from the Santa Clara Pueblo grows up and drops touristy painting to explore her own aesthetic in order to confront the intricacies of womanhood and the pain of being Native in America — and her body of work lives on in legacy.

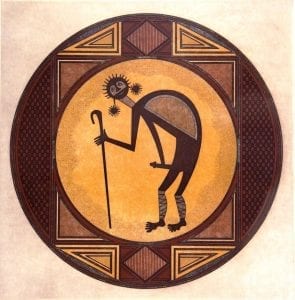

A surprisingly intimate show at The James Museum called Spirit Lines features New Mexico’s late rockstar painter Helen Hardin, her mom Pablita Velarde (credited as the first Native American woman to paint professionally full-time) and Helen’s daughter Margarete Bagshaw, a dynasty of successful women painters. Hardin is considered one of the most innovative Native American artists of her generation.

Hardin was born in Albuquerque NM and grew up painting with her mom, at first imitating her style and eventually growing into her own visual voice. By the ‘80s, she was selling so much work she could barely finish one piece before a buyer would claim it and she was on to the next.

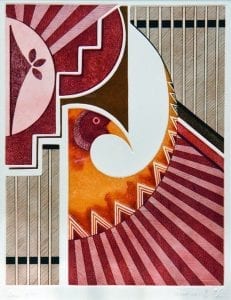

Her design-heavy style is a spiritual mix of lines and colors, and she took pride in being self-taught and contemporary in her approach to images. While she did attend the University of New Mexico for architecture and art, she was deeply active in her craft long before enrolling at the University.

Perhaps as a response to the demand for her work, in the last years of her life she focused on 23 etching plates to make prints. The show contains the first prints of these etchings.

“I think the real meat of my paintings is when I can get into the details and use my gadgets and just fill in all kinds of spaces with designs,” she explains in a 17-minute video that streams in the show, talking while she works on a piece in her studio. “I really love designs.”

It all started in high school when the nuns decided she’d taken too many art classes and by senior year would have to take something else, but Hardin put her foot down and went insistently to the Dean. Classes were separated by gender at the time.

“She said it didn’t fit into my schedule and the only way I could get an art class is to take art while the boys were taking drafting,” Helen said. “So I took art while the boys had drafting.

“Out of the corner of my eye, I saw everything they were doing and what they were using and how they were using it. It really didn’t sink in for a long time. . .

“Years later when I decided I would paint for a living (I didn’t like to do anything else), I started using gadgets more and more and they really become quite useful — I get very perfect lines and edges, I get a lot of detail in with fine lines. I like to use pens for linework and fill in tiny little corners and get a better painting.”

This touring exhibit was organized by Golden Dawn Gallery in Santa Fe and pieces by some other artists were added by James Museum Curator of Art Emily Kapes. They already have Hardin’s work in their permanent collection and this show is a perfect fit.

“The feedback has been really amazing,” Kapes says. “It helps to share her personal life, it really bring her art to life. Helen Hardin’s daughter’s work is in the exhibition, too — Margarete Bagshaw, named after one of Helen’s biggest supporters. It was a pretty special relationship Helen had with the first Margarete, who helped her promote her work in a gallery.”

Helen showed interest in art at a young age and sold art alongside her mothers at shows. Both of them would go on to win a record number of blue ribbons at the Santa Fe Indian Market.

Helen Hardin’s approach to abstracting traditional imagery and indulging in the serene feedback loop of complex and colorful tight design work really draws the viewer in, while pointing to an innate independence in the artist.

“I’m not the American housewife but on the other hand I’m not the woman’s liberator,” Hardin says. “I can’t get into movements — whether they’re women’s movements or Indian movements, I’m just not programmed for that. . .

“I don’t imitate any artist and I’m completely my own person. I don’t think any other artist around for miles would put the energy into four square inches of space as I do in a day.”

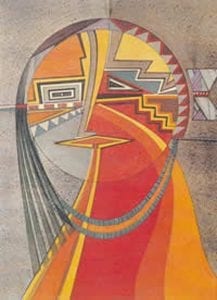

After a breast cancer diagnosis at 38 years old, it might have been a sense of urgency that moved her to focus on creating etchings and prints. Of the 23 etchings she made, three have become some of the most significant works of Native art: Changing Woman, Listening Woman and Medicine Woman.

Hardin started with Changing Woman when she switched to etching in response to demand for her work.

“Changing Woman is a face divided in half. . . she’s a woman who has a profile and she’s looking within herself and yet she’s looking out into the world. I named her Changing Woman, which is a mythical figure in Pueblo and Navajo lore, but the fact that she’s named Changing Woman has nothing to do with the mythical figures, it was just a convenient title and a lovely name for her. Someone said, ‘Are you going to do another one?’ I thought that would be fun, so I did Medicine Woman.”

Medicine Woman is the only one in the series who wears feathers.

“She has a healing spirit so she is entitled to wear feathers,” Hardin explained. “The Medicine Woman is a healer but not necessarily a nurse or a doctor. She could be your mother, nursing you from a cold, she could have that kind of spirit — and I think all women possess that healing spirit.”

Listening Woman looks straight forward and she’s very bold, listening and looking directly at you.

“She seems to appeal to a certain group of women, like psychiatrists and lawyers have been buying her,” said Hardin.

“I don’t make these things for sale for a group of people. Certain groups of people are drawn to them. I’m doing a fourth one that will end the series, called Creative Woman. And this has been the hardest one for me because it has been close to me.

“I told someone it’s like trying to get pregnant and I can’t quite conceive the idea yet, and I hope I can come up with the image next fall. It’s an important series because it says something about women that I feel very strongly about, which is women don’t just sit around being blobs.”

Hardin died in 1984 before completing Creative Woman, intended to be the fourth in the series.

This exhibition also includes select works by other women artists

connected to Hardin through family or Santa Clara heritage —

Hardin’s mother Pablita Velarde, Hardin’s daughter Margarete Bagshaw

and several members of the famed Tafoya family, including Tammy Garcia.

You can find out more about the art

of the Santa Clara Pueblo here