The Tampa Museum of Art

August 28-January 5

Tampa Museum of Art

Details here

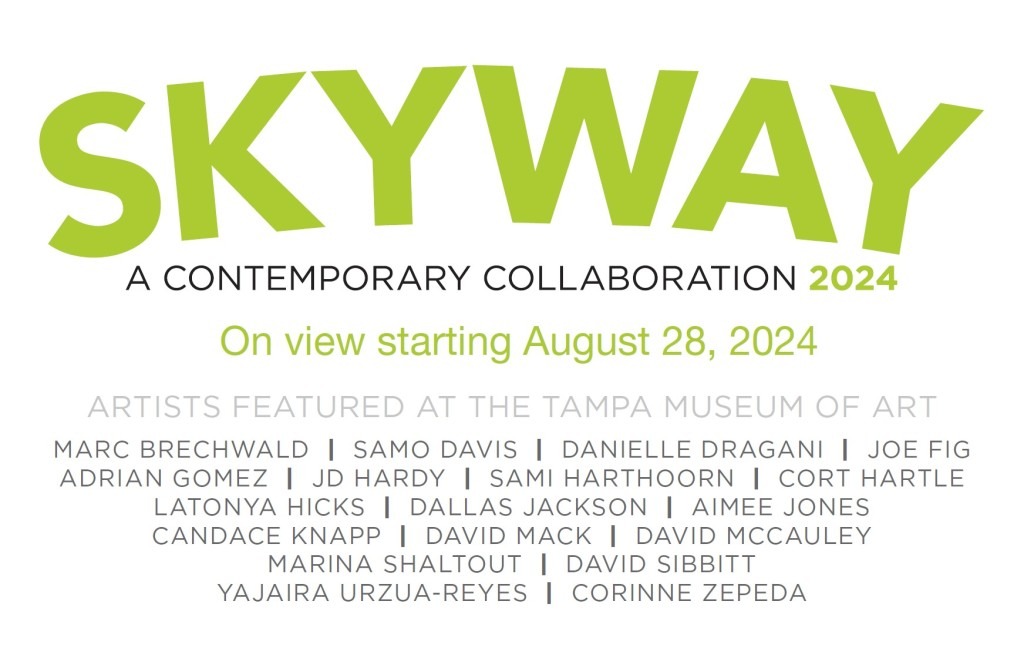

At the end of August, the fifth and final leg of the Skyway 2024: A Contemporary Collaboration will open at the Tampa Museum of Art. I met with two of the artists who’ll be on view.

Joe Fig is the chair of the Fine Arts and Visual Studies departments at Ringling College of Art + Design in Sarasota, and Samo Davis is a digital and graphic designer for the Sarasota Art Museum.

Both artists create new worlds with their art. Together, they represent a return to figuration that’s founded upon the principles of modernism.

Fig sculpts hyper-realistic miniatures of artists’ studios, and paints viewers taking in art at museums and galleries with a kind of realism and figuration that recalls the Dutch Masters.

I met with him in his studio where he showed me the works he’ll be showing in Skyway, as well as those that he’ll be showing in November at the Sarasota Art Museum for his exhibition titled, Contemplating Vermeer. We also discussed his books Inside the Painter’s Studio and Inside the Artist’s Studio for which he interviewed several artists about their creative processes.

Joe Fig – Early on, my biggest influences were Eric Fischl, because he was doing figurative paintings, and David Hockney’s photo collages. Those joiners are still how I build compositions for my paintings – it’s all through photography.

I used to do it that same way by cutting photographs, building them, and making paintings out of them. Now, I use Photoshop, but I like that hand element.

Red Grooms was another influence, specifically his installations. And another was the 1974 book by Studs Terkel called Working: People Talk About What They Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do, – interviews with people like train porters, bellhops and shoe shiners, but also CEOs and executives like Ted Turner.

I had about ten years between undergraduate and graduate school. I was working at School of Visual Arts in the administration while moonlighting as a bartender, and I was interested in how to make a living as an artist in New York City. So, I started interviewing artists I knew.

The first one was Michael Goldberg. I went down to his studio, which used to be Mark Rothko’s studio, it was down on the Bowery – and I was there to make a sculpture of his painting table when he just started telling me all of these amazing stories.

He said his studio used to be a gymnasium, and there, he had a raised platform — like a loft space — which made the space seem like being in a theater. When I left, I thought, “Shit. I should’ve recorded that.” So, I went home and came up with some questions, and I just reached out to all these artists and started interviewing them.

At some point, I started getting into making sculptures of artists’ studios. When I went to grad school at School of Visual Arts, I’d just made one, but I started making more – of historical figures in the abstract expressionist movement like Jackson Pollock and Clyfford Still.

Tom Winchester – You’re making a connection between the motivations for making your work and interviews. It’s a creative process that mixes familiar artworks with aspects of the artists’ lives that are unpictured. Your work creates a closeness to the artists in a way that’s similar to the 1972 documentary Painters Painting, and you even have a painting of Robert Rauschenberg on a ladder, which is a scene from that movie.

I feel closer to the artists you sculpt in the same way that Painters Painting makes me feel closer to Jasper Johns and Barnett Newman. It’s as if their artwork isn’t the full story. We all know Clyfford Still, but we really don’t know him until we see his studio.

JF – That’s one of my favorite movies. For that painting, I got to go to Rauschenberg’s studio on Lafayette Street and Great Jones Street. He had a show in Hartford, Connecticut, which is where my wife’s family is from, and I got the number of someone who worked for him at that show.

So, they let me into his studio on Lafayette when he wasn’t there. I was in the room where they shot Painters Painting. I used that visit as reference for the space and made the sculpture based on what I’d seen in the film.

The cool part is that they let me down in his basement where he had all of his files and photographs in envelopes – I was going through images of artists like James Rosenquist and Jasper Johns. And it was so cool.

Apparently they showed him my sculpture and he said, “He’s drunk as a lord.” Lol!

In 2006, I had an exhibition of painters’ painting tables, and the format was to show the sculptures alongside audio of the artists talking about their work. I had a CD player, and you could hear them answer questions, which were all the same for each artist.

They were all painters, which led to my first book titled, Inside the Painter’s Studio. I had never intended to write a book, but I had all these interviews, my documentary photos from their studios, and my own work.

My interview process was to ask questions like, ‘Where’d you grow up?’ ‘Where were you born?’ ‘How was your high school arts program?’ ‘Where’d you go to college?’ ‘How’d you end up moving to New York?’ ‘How’d you get your first gallery show?’ ‘How’d you set up your studio?’ And through the process, I’d get insight into their work.

I’d ask, ‘What’s the earliest artwork you made as a kid?’ And Tom Otterness said, “It’s this lion I made. I painted it in an abstract form from a ceramic model… and here it is!” He was like in his 60s, and he still had this thing with him that he’d made in the third grade.

What are the sculptures made out of?

JF – 95% of these are handmade, and the rest are purchased from a store where they sell items for dollhouses. Some are made by using materials like artist’s medium, blocks of wood, pieces of plastic, Sculpey or toothpicks.

My self-portrait is of my first studio. It’s a sculpture of me working on this sculpture. If you look through the window, you can see a miniature version of me and my face in the reflection in the mirrors.

The experience viewing the self-portrait is a bit different from the others because you have to peek into it.

JF – I made a few full houses like Eric Fischl and April Gornick — which is the biggest one I’ve made — Ross Bleckner, Chuck Close, and they take a looong time to make. They’re very detailed. I like that you have to peer into them.

There seems to be a connection between your propensity for realistic painting and the motivation to take realism off the canvas. It’s a type of uber-realism in model form.

JF – I’ve always been interested in portraiture. When I was at SVA, in the late ‘80s, no one was doing figurative work except for painters like Eric Fischl, David Salle or Philip Pearlstein. There weren’t very many people.

I was also interested in sculpture, and for years I did pseudo-sculptural paintings. My question was, ‘How do I make portraiture contemporary?’ That’s what I’ve been working with, and these works became indirect portraits.

In a way, they’re also inspired by when I was 18 or 19, my brother and I would go clean offices at night. We’d go to, for example, a trucking company where there were all of these cubicles, and we’d empty the garbage cans – people smoked back then, so we’d empty the ashtrays.

I’d look at their cubicles, there’d be all of these family photographs, and we’d make up stories of all of these people. Even though they weren’t there, their being was there.

This work came out of that—looking at the artist’s studio as a portrait. Not so much the figure, but looking at the space as a form of portraiture.

What kind of research do you do for these sculptures? Are they all based on your own photos?

JF – Initially they were from books, but I only made about four or five sculptures like that.

When I went to Pollock’s studio, which wasn’t a big space, it was basically a barn – there was a much different feel by being there in the space than just using photographs. So, I took that experience and I realized that the interaction is really important. That’s when I started reaching out to contemporary artists. And I’ve been mostly focusing on contemporary artists ever since.

Your work is as much about research as it’s about portraiture.

JF – Some people compare it to documentaries, anthropology, history and chronicling — I like all that stuff.

I’ve noticed that as time goes on, and things change, they start to take on even more significance. You’ll see a wall phone, for example, in my self-portrait – and we don’t have wall phones anymore. Or I’ll do a portrait of a person and then they’ll pass.

Which paintings will you be showing in Skyway?

JF – I’ll be showing paintings of people viewing works by Edward Hopper, Nicole Einsenman, David Hockney — the Hockney painting is of a huge photograph at Pace Gallery where it had him in there, so it was similar to my work of an artist in the studio — Barkley L. Hendricks with two Whistlers at the Frick Collection, and Joan Snyder.

There’s a really good profile of Alex Katz in The New York Times, where he said something like, ‘The vocabulary or grammar is all out of abstract painting. That’s what makes my paintings different from all of the figurative painters.’

That’s how I felt when I was at SVA, when there was no figurative painting and abstraction was the thing – that even though I’m making figurative-based work, the figures are irrelevant, in a way. I paint standing up, on the wall, like the abstract expressionists did. I don’t sit down and render. I’ve always done that.

For the paintings of people at art galleries, my rule is the people in the paintings need to be at that exhibition. They’re not necessarily in those spaces or spots – I compile photographs of them and piece them together in Photoshop.

I spend a lot of my time on the composition – it’s where the work goes in, and that’s where the formal choices come in. ‘How can I move them around to get a good balance?’ Once I have the composition, it’s just about painting it and I don’t have to worry about where things go.

I think it’s really unique how you include the gallery’s wall text in the paintings. It brings in the systems around the art world like curation, institutions, and how opaque and exclusive art seems to the layperson – as if art needs to be explained. Considering your pseudo-collage creative process, it’s interesting to me that you choose to include details like that.

JF – Without that, it seemed like it was missing something. Yes, they’re wall text, but the horizontal of white, going across, balances out the composition.

You’re making small paintings. It reminds me of Arnold Hauser’s point in his 1951 book The Social History of Art about how socialized economies in the Baroque era, like the Dutch, could afford to paint in their houses, and therefore they made small paintings.

JF – Then, paintings were made for homes. Before these, I was doing large, seven-foot paintings, but I didn’t like that. Like my sculptures, the viewer zooms in and gets focused in on these paintings.

I love this scale for that reason, that intimacy. It’s more of a domestic scale.

Samo Davis uses multi-colored materials like cotton pom-poms and melted plastic to sculpt extraterrestrials discovering new landscapes with the chromatic array and fantasy of Superflat artists like Takashi Murakami and Yoshitomo Nara.

We met at a coffeeshop across from Ringling College, and I took a portrait of her while she was on-the-clock at The Sarasota Art Museum. She told me about her creative process, the fantasy and myths inspiring her work, and how motherhood has influenced her art.

Samo Davis – I live in a small house. I don’t have a studio space, but I started creating this 12-foot puppet that’s kind of a humanoid tree figure that’s stepping out into a foreign, alien landscape, reflecting on herself.

It looks like it’s walking. It has a kind of arched-back feel and, the way that it’s held, it has its arms out and its legs as if they’re in motion. So, it’s as if it’s stepping out for the first time into our world.

You can’t really tell what it is or who it is, but it’s supposed to feel like an introspective look at yourself, when you’re looking at it. ‘What is this? Who is this? Is it me?’

I’m also creating a lot of growth on the ground. It looks like it’s leaving these growth footprints. I want it to feel like it’s the biggest thing in an alien land and it’s stepping out into a place where everything is reflecting onto itself.

I have some creatures that are going to be around the main figure, and I’m not sure yet how it’s going to be spaced, because that’s the site-specific part.

The creatures are in reference to different Japanese and Singaporian fables, and I want them to be signifying a ‘stepping-out’ mentality. One fable I’m referring to has a monkey, a rabbit and a fox, and it’s about how a rabbit shape came to be on the face of the Moon. The monkey I’m including in my piece has anime colors on the outside with vibrantly rainbow-esque eyes on the inside.

I went through a caterpillar phase where I made like a million caterpillars. And then I went through a phase where I was obsessed with pigs – I took pictures of pigs, looked at pigs online and snapped screenshots of them. I have like millions of pictures of pigs in my phone.

One piece is named Piggle, for the lack of a better title right now. It’s kind of an alien-space pig. It’s made out of plastic and recycled materials, and has pom-poms inside of it.

I melt it in hot water and form it with my hands. He’s going to be one of the characters in my work in Skyway.

The pig is based around when I was pregnant. Before I was pregnant, people used to ask me, “Are you pregnant?” I’d be like, “No.” It’s really not cool to be asking somebody that. So, this piece is a reflection on that.

I want all of my characters to be reflective of who I was while making the work. The pig story is about my pregnancy.

Another piece is about being hard on the outside and being soft and mushy on the inside. I want things to be representative of things that have happened to me in the form, loosely, of animals from parables.

Its colors are almost psychedelic in that it looks like every color in the Crayola box. What is it made out of?

SD – I use a lot of pom-poms — I inherited over a million pom-poms from a friend who passed away last year. He was like, ‘All my pom-poms go to Samo.’ So, it’s pom-poms, melted plastic, concrete clay, glow-in-the-dark paint, resin and some glass.

What is the inspiration behind your maximal color palette?

SD – I’m Japanese. I never really grew up in Japan, but I get inspired by the Superflat movement and the work of Takashi Murakami. When I look at pieces that have that sort of color, that’s what inspires me, and I want people to get excited and feel that same feeling.

So, when I’m working on something, I feel like it’s never colorful enough. Lol! I want to explode your imagination. Pop!

How does your work relate to Pop art?

SD – I never want to be defined as anything. I take inspiration from Pop’s use of color, but I feel like everything else I do feels like illustration, drawing and sculpture. The way that it looks is supposed to feel alien and organic.

Do you think anything culturally comes through in your work?

SD – Yeah, I think there’s a lot of plants from living in a tropical environment. Growing up as a third-culture kid, there’s some of that. And being exposed to the culture in New York while I was at Sarah Lawrence College and Parsons School of Design, including going to the Murakami retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum.

While I was at Parsons, I did fashion design, so I feel like some of the choices I make come from that. For example, crinoline is used a lot in hats, like those with a fancy bow that’s made of mesh.

A lot of the artists In the Tampa Museum Skyway are showing work that refers to their personal stories. It’s reflective of who we are individually and how we portray ourselves, artistically.

As artists, I feel it’s our job to let people understand our work from their experience.

The opening of Skyway at TMA will signal the beginning of the end of the quintuple-legged exhibition, at least until its ostensible next iteration three years from now. With artists such as Fig and Davis on view, this final leg seems like it’ll have us all sprinting over the finish line, not tripping before it.

Their creative practices are just two examples of the high level of artistic prowess the Tampa Bay region has to offer. From the south side to the north side, Skyway serves to bridge our local artistic community, and showcase amazing talents working in Tampa Bay.