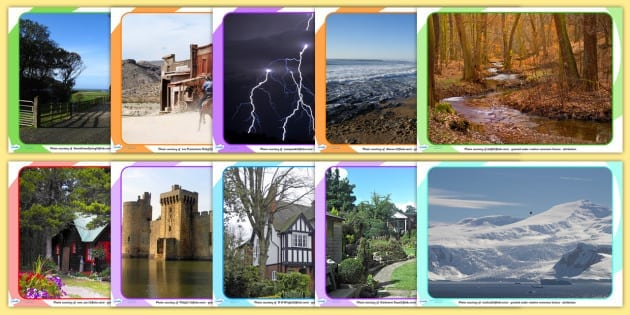

Setting

There is a silent character in all great theatre, and that is setting. All of my favorite playwrights (and novelists) use setting not merely as the place where the action occurs but rather, more importantly, as a force that drives the action, motivates the characters, imbues the language, sets the tone, and enforces the thematic underpinnings of the play. Tennessee Williams and Martin McDonough are two playwrights that have had a huge influence on me – both dramatists are masters of using place to create the world of the play and to evoke emotion. Williams was so exquisitely specific that when writing about the setting in Streetcar, he went so far as to define the New Orleans sky: “The sky is peculiarly tender blue, almost a turquoise, which invests the scene with a kind of lyricism and gracefully attenuates the atmosphere of decay.” And in McDonough’s plays he creates a rural Ireland that tempers the language, the rhythm and the hearts of his characters.

Many new dramatists seem to dismiss or perhaps overlook setting. In a lot of new plays that I see and read, setting feels like an afterthought rather than something that the playwright wove into the story with any kind of purpose. This might be a symptom of the trend toward politically charged theatre where stories for the stage are fueled by the message rather than the emotion. Or maybe, most audiences don’t care and I’m the odd theatregoer who wants to be transported to a specific place – the distinct world where these characters live and breathe and tell their story. It might be simple or just old fashioned of me, but I wish more theater were rooted in a place.