By Tom Winchester

. . .

Skyway: A Contemporary Collaboration 20/21 was a great opportunity for locals to visit the museums in our area to see some of our own. It gave all of us a reason to cross the bridges for a few weekends of art-related staycations. In doing so, we not only supported local art institutions, but our local artists.

Skyway 2017 was the first iteration of this multi-venue exhibition. Since then, Skyway has grown by one more museum as well as one more county represented by an artist. Skyway 20/21 was a collaboration between The University of South Florida Contemporary Art Museum, The Museum of Fine Arts St. Petersburg, The Tampa Museum of Art and The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, and lasted for about three months.

The motivation behind the Skyway exhibition is to showcase local artists. You have to have to have a connection with the Tampa Bay area to be included. Each artist’s connection is different – some live here, and others are from here. Submissions are judged by the curators of the participating museums as well as a guest curator. For Skyway ’21, the guest curator was Claire Tancons, who has experience curating biennials and large group exhibitions all over the world.

The initial schedule for the exhibition was during the summer of 2020, but that was pushed back due to COVID-19. In the exhibition’s catalog, the curators mention how Skyway ’21 is intended to reflect the turbulence of that summer. COVID-19, Black Lives Matter, attacks on the AAPI community, and pollution are some of the topics mentioned in the artists’ and curators’ statements.

Guest curator Claire Tancons describes the exhibition as a rhizome. “A rhizomatic exhibition. . . embraces proximate and contrary elements, like-minded and opposite ideas, circumventing conceptual divergences and cutting across stylistic preferences to form a creative ecosystem, inclusive of the widest variety of artistic species.”[1]

One interesting curatorial factor for this exhibition is that it’s installed in four spaces that couldn’t be more different. Each museum involved has a distinct programming style, as well as site-specific architecture. This means the artworks of Skyway ’21 interact with contexts that span the course of human history.

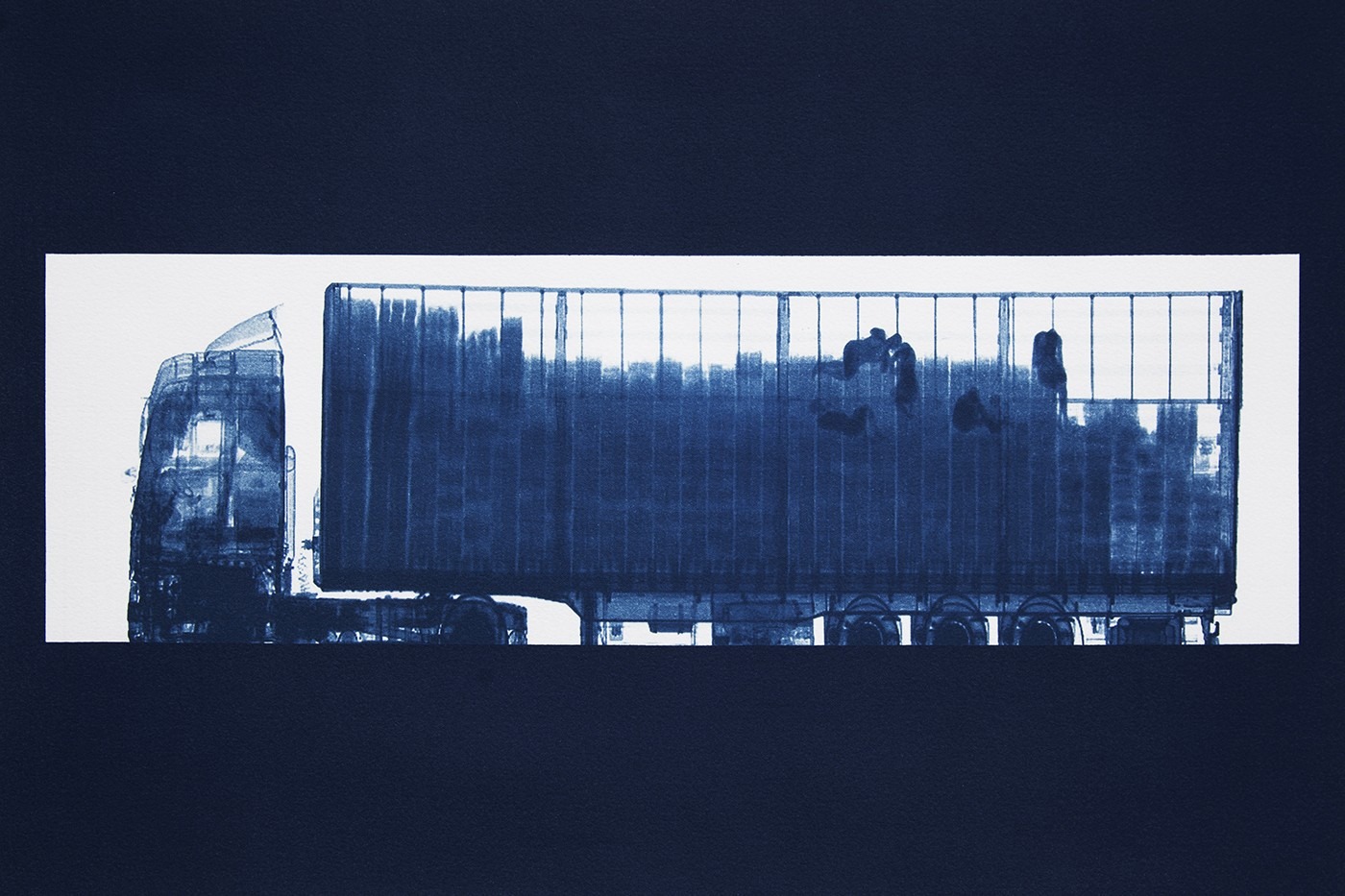

The Baroque galleries of The Ringling Museum housed some of Skyway ‘21’s largest works. Kalup Linzy’s cinematic OK (2021) was projected in a blackbox theater where viewers could experience it as if seeing a Hollwood blockbuster. Ya Levy La’Ford’s room-sized installation titled, Unloaded (2017), consisted of glowing blue light emitting from behind geometric shapes hanging on the wall, and made the gallery feel like a spaceship. Noelle Mason’s mural-sized cyanotype of migrants in the back of a box truck – as seen using surveillance X-rays – is so big that the truck feels like it’s in the room.

The postmodern trapezoid of USFCAM housed several fiber-based artworks. Rosemarie Chiarlone‘s Consequence (2019) is a series of small embroidered silk pieces that have textual phrases sewn in to them. Akiko Kotani’s Red Falls (2021), made from crotched bright-red polyethylene, looks like a giant chunky-knit scarf hanging from the corner of the gallery.

Cynthia Mason’s canvases vacillate between paintings about the formal history of painting and phallic protrusions about that history’s misogynistic canon. Casey McDonough’s web of pink and purple yarn, and dainty gold necklaces that look like they were bought at Claire’s, create a delicate, yet impenetrable shape.

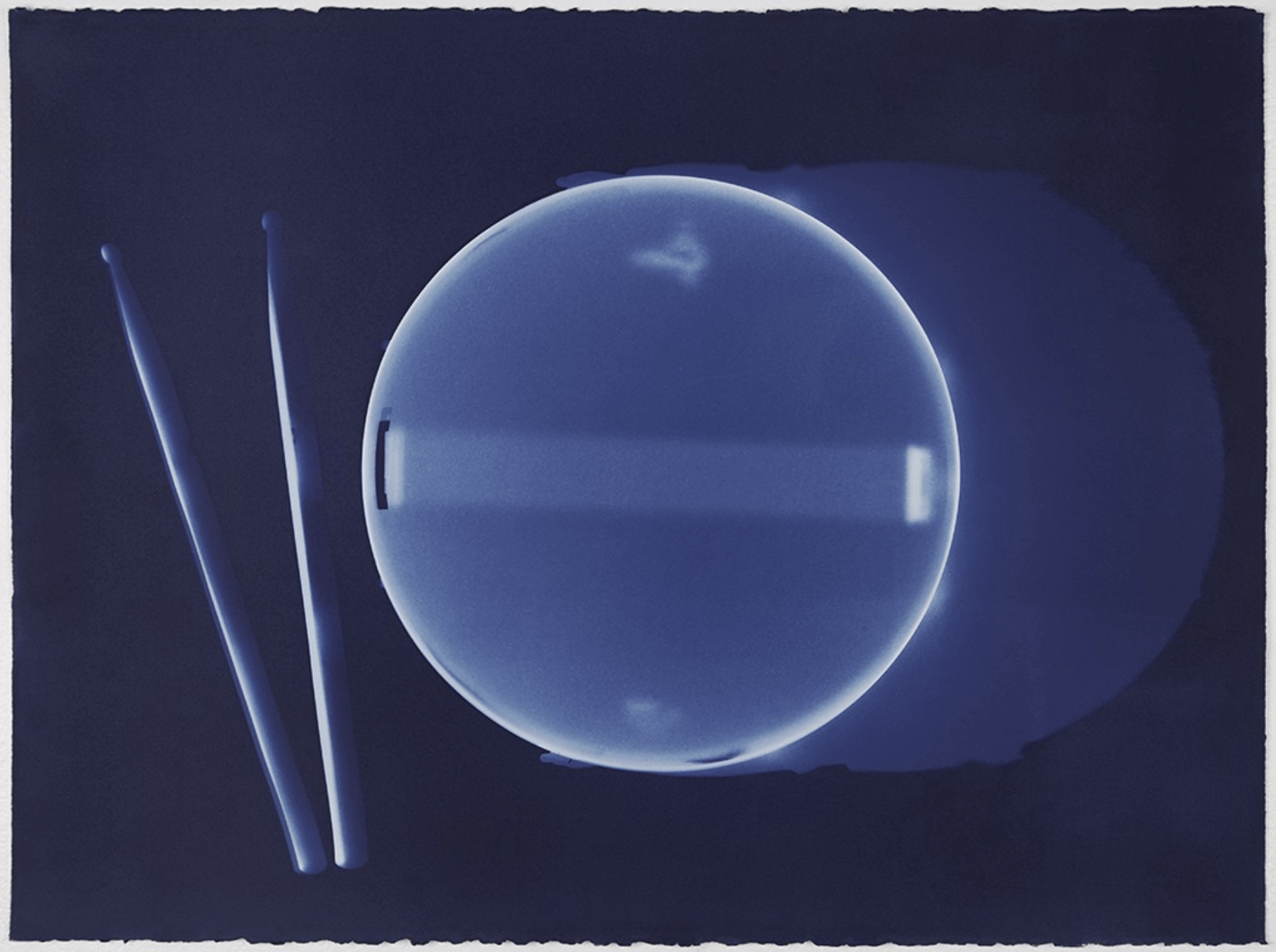

The Tampa Museum of Art’s chic, modern galleries were dominated by cyanotypes and pop art. Jaime Aelavanthara and Amanda Sieradzki collaborated on the cyanotype photogram Blueprint/Redbloom (2021), which uses a bedsheet to depict a human silhouette in a blue ocean. The cyanotype photograms on view by Wendy Babcox depict the silhouettes of circular drum heads and drumsticks.

Libbi Ponce’s Theresa’s Plane (2020) resembles a scaled-up trompe-l’oeil of a collectible figurine that’s presented on a pedestal of interlocking floor tiles. Kirk Ke Wang’s Yellow Man (2020-2021) depicts a yellow silhouette on a dinner table surrounded by an extended-family’s worth of people and floating emojis.

A possible takeaway from Skyway ’21 is that abstract photography has once again advanced to the fore. Even representational photographs were presented in ways that abstracted their depictions. Specifically, the exhibition had a surprising amount of photograms on view, including cyanotypes and traditional, black-and-white, silver-gelatin prints.

A photogram is a camera-less photographic process that creates a silhouetted image when an object or person obstructs light while exposing light-sensitive emulsion. Because there is no camera, photograms are ostensibly empirical records of those exact few moments of interaction when light was being exposed. Compared to the perfect representational power of digital photography, photograms create abstract depictions.

In the past, photograms have been used by artists like László Maholy-Nagy, James Welling and Walead Beshty to point to the manipulative capacity of photography, and to bring attention to how photographs tell lies. Aesthetically, the photogram can point to the idea of making photographs that are more truthful, and more meaningful.

Noelle Mason, Jaime Aelavanthara and Amanda Sieradzki, and Wendy Babcox all use the cyanotype process to make their photograms. They employ the spatial compression of the photogram – and its exclusion of details – to cut out the “noise” and focus on certain issues with precision.

Babcox’s crafty hand in making the snare drums that accompany her photograms on view, is reflected in the painterliness of the cyanotype. Aelavanthara and Sieradzki’s life-sized silhouettes of a dancer create an intimate connection both by being depicted on a bedsheet, a very personal object, and by knowing that the dancer was actually there, in person, laying on it when the emulsion was exposed. Mason’s X-ray view of a box truck smuggling migrants takes on an activist tone when presented in a medium that has been used throughout the history of photography as an aesthetic means of telling the truth.

In terms of photography, judging by Skyway ’21’s emphasis on abstraction, you might think the art world has returned to a style akin to the ‘Pictures Generation’ – a movement during the 1970s and ’80s driven by the idea that the world as seen through photographs was reproduced to the point of meaninglessness. Thus, photography became the target of critique by artists like Cindy Sherman, Laurie Simmons and Richard Prince.

Noelle Mason says about her work, “I don’t see any truth to be found in photography as a medium. The only truth to be found in photography is to go outside of it. That’s the dialectic that my work attempts: to approach photography not as truth but as a lie that is only partial. . . I use images more as a means of figuring out what is left out of the image. . .”

I’m not sure we ever left the Pictures Generation. There was a moment in the early 2000s when photography went through its Greenbergian ‘paint is paint’ period and abstraction came back hard, but the appropriation that defined the Pictures Generation never really left. I guess that’s the thing about postmodernism, the remix is endless.”[2]

Janelle Young’s black-and-white diptych consists of a photogram juxtaposed with its representational counterpart. On the left, a monochromatic cluster of leaves and twigs floats on a background of white. On the right, slivers of white and gray sitting at the bottom of a field of black make it look like a freeze-frame of fireworks from the 1950s.

Young’s Infinity series exemplifies the theory of self-referentiality in photography, an attempt to disrupt Roland Barthes’s premise that photographs always point to a moment in the past. Young’s artist statement reads, “The ‘Infinity’ series is a self-referential study of objects collected from the natural world.”[3] Walead Beshty’s Picture Made by My Hand With the Assistance of Light (2007), a series of photograms of a crumpled sheet of photo-sensitive paper, was created as an overt illustration of this theory – and serves as a precedent for Young’s Infinity series.

Young’s creative process for Infinity consists of placing an object in front of a photo-sensitive sheet of paper and using an on-camera flash to simultaneously illuminate the shot being taken, while also exposing the sheet of paper. The result is a dual image that represents an expansion of the same moment – two separate frames of the sequence of life.

Young expands time in a way that resembles Robert Rauschenberg’s Factum 1 and Factum 2 (1959) and Natalie Krick’s Negative / Positive and Positive / Negative (2020). These works are all created at the same time, respectively, and they’re presented in ways that question their sequence of creation.

Selina Romàn and John Notwick both exhibited photographs that are mostly representational, but the ways in which the artworks were presented served to abstract their depictions.

Romàn exhibited close-up self-portraits that excluded any identifying features in order to focus on the pastel colors and textures of the sheer fabric encompassing her body. The photographs were presented with color-coordinated geometric shapes painted on the wall around them. The presentation created an illusion that merged the artworks with their environment.

Notwick’s black-and-white photographs depict military test sites in Florida, and they’re presented in the hue of each site’s hazard-level rating. Alarming colors of red, orange, yellow and blue wash over the lightest areas because each image is behind a plane of plexiglass saturated with one of those hues. They exude an overall sense of paranoia about an environment overcome by the war machine.

Another possible takeaway from Skyway 20/21 is that fiber art is currently acting as a safe medium where intimate — sometimes difficult — ideas and feelings can be expressed. As conveyed by the curators in the exhibition catalog, 2020 was a year when divisive social issues surfaced around racial injustice at the same time the entire world was told to stay away from each other. Our personal spaces became our work spaces, and our public spaces became forums for protest. Curating artworks made from soft, inviting fabrics – and domestic objects that refer to a common experience – may offer a tone of unity during this divisive time.

Skyway 20/21 includes a variety of fiber-based artworks, including the cyanotopes printed on bedsheets by Jamie Aelavanthara and Amanda Sieradzki. Cynthia Mason’s canvas wall reliefs are so soft and touchable they beg viewers to break the cardinal rule of “don’t touch.” Presented as objects to be admired, they create a relationship with the viewer that reflects the underlying misogyny in the history of painting.

John Sims’s hanged Confederate flag distorts the icon of hate to a point where its identifying characteristics are still recognizable – but not in full sight. It’s abstracted to the point where it serves as a sign for all flags that represent an inexcusable history of slavery and institutionalized racism. The artwork uses the form of a flag, an object hanging in classrooms and outside homes, to remind us that we all share a history that should never be reincarnated.

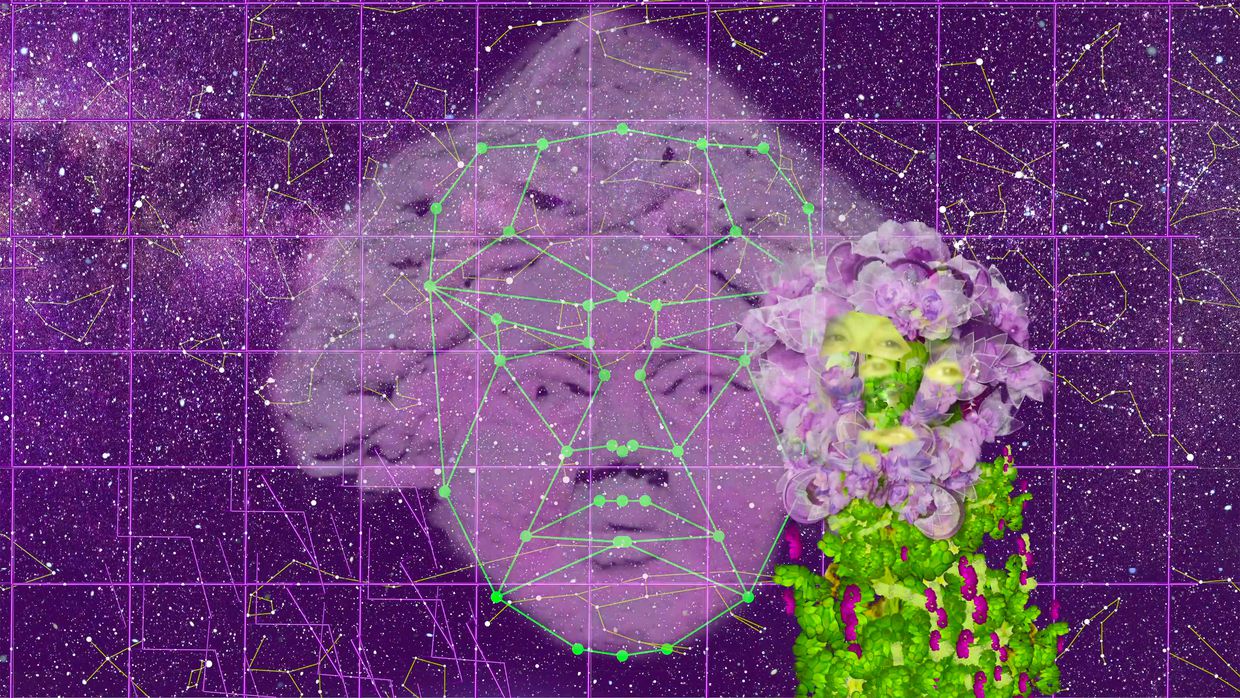

A nuanced tech-themed aspect of Skyway ’21 might have gone unnoticed if you didn’t visit each site of the exhibition. Easter eggs of motion graphics and new media appear in the least likely places. Dakota Gearhart’s Life Touching Life (2021) is an existential dive into the digital realm organized as a chat show. Its host, a toxic algae bloom named Tiffany, is formed from the manatee-killing sludge that’s at the center of Florida’s current pollution crisis. Her existence is because of corruption in government that benefits commerce, a theme Gearhart often employs to discuss the military-industrial complex.

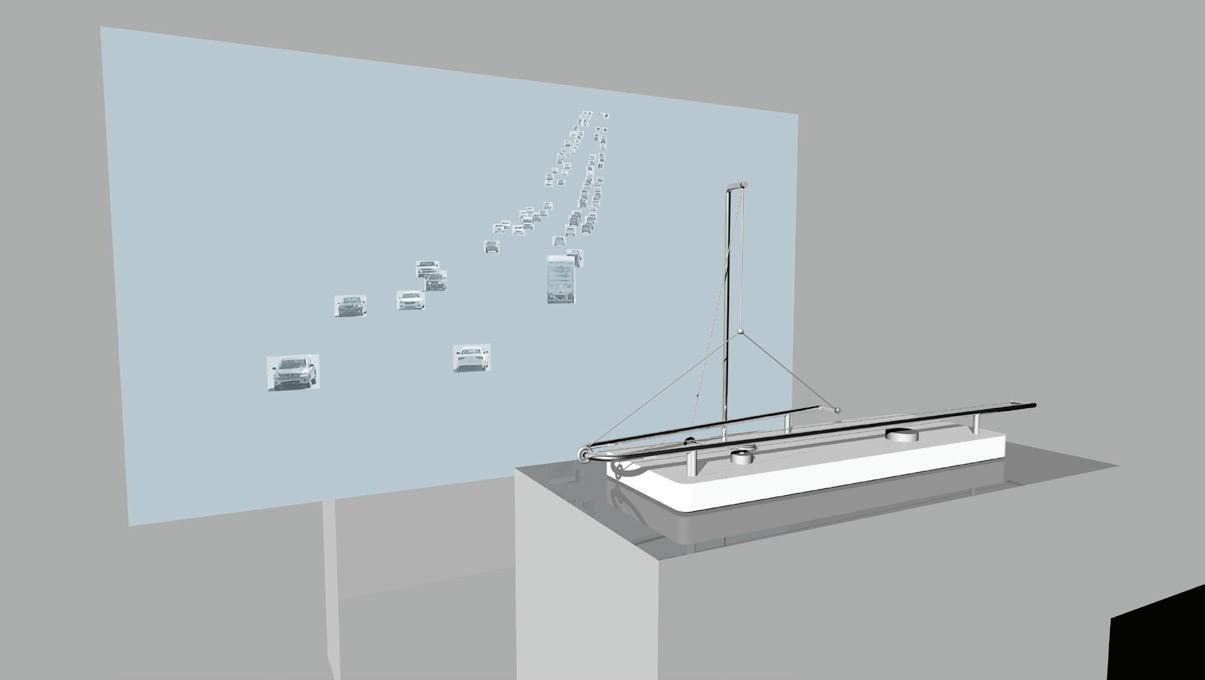

OK! Transmit’s Overflow (2021) is a reflection on the overwhelming amount of data being created – and collected – about each of us on a daily basis. In the gallery, a projection shows glitchy cars crossing a live video feed overlooking the Bob Graham Sunshine Skyway Bridge.

A pedestal placed several feet in front of the projection supports a miniature replica of the Bridge. The replica clicks and plucks in concert with the projection because it’s linked to sensors triggered by the movements of cars actually crossing the Bridge. The result is a generative, multi-media artwork created by a network of anonymous collaborators.

Curatorially, the exhibition confronts contemporary issues with avant-garde artworks. Difficult issues like racial injustice, misogyny and pollution are dealt with directly — no sugar-coating — by this collection of avant-gardists, just as previous avant-garde movements dealt with the issues of their own times.

Like Andy Warhol’s Brillo Boxes (1964), in Dakota Gearhart’s Life Touching Life there’s no question whether the work involves issues surrounding the capitalist machine. Like Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (1937), John Sims’s The Proper Way to Hang A Confederate Flag (2004) represents a strong stance on a divisive issue of the day. Like the Bauhausers and the New-York-Schoolers, these artists are using abstraction to battle the manipulative capacity of representation – and to tell their stories in more truthful ways.

It’s no surprise that a four-museum-wide showcase of artists from our area produced such an impactful exhibition. Skyway 20/21 is another example of the wealth of support our local institutions have for the arts, and how collaborative that support can be. Let’s hope the next iteration is even more expansive than its two predecessors.

Notes:

[1] Claire Toncons, Skyway: A Contemporary Collaboration 20/21 (Saint Petersburg: Museum of Fine Arts, 2021) .

[2] Noelle Mason in conversation with Tom Winchester

[3] Janelle Young, Artist’s Statement for Infinity series, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5ae0c60150a54f5ac72aaee1/t/5b1a8263575d1f79b922159e/1528463971758/J_Young_Artist+Statement.pdf (Referenced 10.10.21)

[4] Gottfried Jäger, “Concrete Art—Concrete Photography,” in Fotografie konkret—Konkrete Fotografie (Vienna: Ritter Verlag, 2006), 24-29.